Prime Minister Narendra Modi will be visiting China for his first substantive bilateral engagement with President Xi Jinping about 10 days before he completes one year in office (May 25). It would be by far his most important foreign policy visit.

From the Indian perspective, while there are many economic-trade-investment and connectivity possibilities that need to be enhanced, two Ts namely Territorial dispute and Terrorism concerns warrant candid high-level political review if the Modi visit is to be meaningful.

Long Uneasy Territorial Disputes

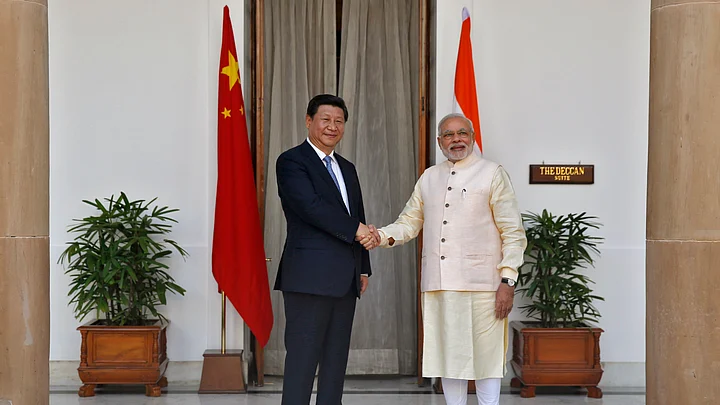

While the first meeting between the two leaders took place in September 2014, when President Xi visited India, it was more in the nature of a preliminary ‘get-to-know’ occasion which was marred to a certain extent by the incursion of PLA troops in Ladakh’s Chumar sector even as Modi was receiving Xi in Ahmedabad.

Whether President Xi knew about the ‘incursion’ and had tacitly approved it – or was totally in the dark and was equally surprised by an autonomous PLA initiative – remains moot but provides the strategic context to the uneasy India-China bilateral relationship.

There is a mirror-image in Beijing of the pattern of incursions, and Chinese interlocutors with whom this author has interacted have offered a narrative of the Chumar incident that includes aggressive patrolling by Indian troops along the LAC and the provocative unseating of a Chinese officer who was on horseback!

The unresolved territorial and border dispute continues to fester more than a quarter century after the tentative rapprochement that began with the 1988 visit to China of then Indian PM Rajiv Gandhi.

However, unlike his predecessors, Modi brought up the incursion issues (including the 2013 Depsang area incident) and the larger territorial dispute with Xi in a forthright manner in September. One therefore hopes there will be a more candid exchange of views and recommendations on how best to resolve this tangled border issue.

A modus-vivendi is possible only if the respective claims and narratives become a little more malleable and this is the core of the Modi-Xi challenge.

Need Concerted Efforts to Tackle Terrorism

The second T, which is the equivalent of the elephant in the drawing room, is terrorism and China’s covert support to Pakistan in this domain. Beijing, for reasons that defy normative strategic logic, chose to provide WMD support to Pakistan as far back as the mid-1980s. Consequently, by early 1990, Pakistan had a WMD advantage over India in having clandestinely acquired both a nuclear weapon and the missile that could deliver it.

From May 1990 onwards, the Pakistan army embarked on NWET (nuclear weapon enabled terror) against India and the November 2008 Mumbai terror attack is the most recent manifestation of this malignancy. However Beijing has steadfastly refused to acknowledge this linkage and the standard Chinese response is to stonewall the entire matter.

Yes, India and China have many areas of mutual benefit ranging from increasing trade and economic cooperation to investment and macro-connectivity projects such as the ambitious Xi led Belt and Road initiative. But all of this will remain stunted and restricted by the glass-ceiling of the strategic and security dissonance represented by the two Ts.

The often heralded Asian century will remain elusive if the continent’s two largest powers are unable to harmonise their anxieties and aspirations. India has a huge domestic development challenge and has to eradicate colossal poverty in the manner that China has – but through the democratic dispensation. The good news is that India is now on an upward trajectory of its GDP with a demographic advantage, and China can be a valuable partner in sustaining this endeavour.

Concurrently, Beijing and the Xi team have their own vulnerabilities. A just released Harvard University report by the Center for International Development, based on the latest global trade data for 2013 suggests that China’s GDP growth rate over the next decade will come down to 4-6%. This ‘abnormal’ exigency will have many unforeseen consequences for the Chinese leadership and India with a more stable South Asia offers a potential growth region that still remains relatively unexplored.

Hence the need for the forthcoming Modi-Xi summit to candidly review and reset the two Ts becomes even more urgent and imperative. The alternative is bleak.