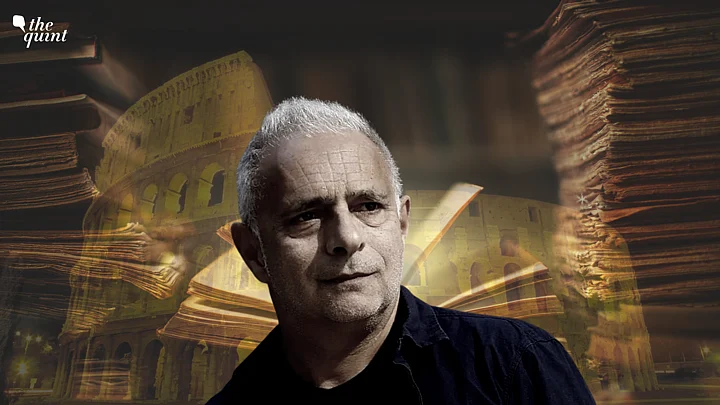

Hanif Kureishi, the British Novelist, screenwriter, playwright and director, has been narrating the most imaginative stories since earlier last month from an unusual place and space -- a hospital bed in Italy under utmost distress.

What has emerged is a striking chronicle of a man coming to terms with an injury most terrible. His Twitter threads, night after night, make his readers laugh and weep all at once, with his typical acerbic wit in place.

His last novel, The Nothing (2017), is centred around an elderly man in a wheelchair, trapped in a frail and frustrated body but still feeling the urge to create. The irony is not lost as Kureishi himself now lies paralysed.

After a grievous injury on Boxing Day in Rome, the writer has been chronicling his recovery in the most remarkable way possible through Twitter threads, collected on his Substack newsletters. Unable to hold the pen, he dictates them to his son Carlo.

“I have never been so busy since I became a vegetable,” one of the dispatches starts, alluding that the writer of the cult classic, The Buddha of Suburbia (1990), has not lost his penchant for arresting opening lines.

Unable To Hold a Pen but the Words Keep Coming

Kureishi considers his pen to be an extension of his body. For decades, the author has been a wordsmith. Novels, short tales, plays, and screenplays have gushed forth, with no fear of being censored.

The writer’s difficulty in grasping a pen, however, is a painful and heartbreaking realisation. In one of his posts, Kureishi expressed the physical act of putting pen to paper, how he likes to “write a word, a sentence, then another sentence, until I feel something wake up inside.”

“As I make these marks, I begin to hear characters speaking, and then they start speaking to each other if I’m lucky; if I’m even luckier, they might start amusing one another,” he added.

“I’m sure many painters, writers, architects, sports people and gardeners love their tools, and see their tools as an extension of their body. I hope one day I will be able to go back to using my own precious and beloved instruments,” he wrote.

It is uncertain whether he will be able to hold a pen or walk again, and so his readers worry and wonder: will the world ever be the same if Kureishi can't write?

He assures in one of his posts, “… I will continue to write freely and spontaneously, as I am doing now. I have never written like this before.”

Kureishi, 68, was born in Bromley, South London, in 1954, to a British mother and an Indian father who immigrated to Britain to study law.

Coming of age in the '80s, he explored the relationship between race, culture, identity, and politics in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain through his work.

He has acknowledged the complexities of identifying with England - its colonialist history and myths of nationhood - but has remained steadfast in his pursuit of what it means to be British and how that complex citizenship may be portrayed.

In the past, he has criticised the Conservative government in England for discriminating against minorities and the working class.

“This row between us and them (the Tories and the conservative press) was also an argument about language and representation. These people wanted to control the freedom of imagination. They were afraid of anyone who saw Britain as a racially mixed, run-down, painfully divided, class-ridden place. For their fantasy was of a powerful, industrially strong country with a central, homogeneous culture.”Hanif Kureshi in his autobiographical essay, The Rainbow Sign.

Situating Asians within ‘Multicultural Europe’

Kureishi became a beacon of hope for a new generation of Asians challenging not only racism but also the traditional image of what it means to be Asian.

All this at a time when Britain was quite different, with racist stabbings and firebombings being ordinary and "Paki bashing" being a national sport. He not only liberated British-Asians from their manufactured identities but also gave real characters, not just stereotypes.

Kureishi's language and representation portrayed Asians that were neither meek nor obedient but rather amusing and casually knowledgeable.

With his best-known screenplay, My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), he told the story of a love affair between a bored Asian adolescent named Omar and a working-class white youngster named Johnny against the backdrop of bigotry and recession in '80s Britain. This love story of two boys broke traditional narratives of immigrant life.

When Nasser, the landlord, evicts a black tenant, Johnny objects that he should not be so nasty to another black person.

"I am a professional businessman, not a professional Pakistani," Nasser says condescendingly. With this small act, he escaped the cage of identification imposed by both racism and anti-racist notions of ethnic belonging.

Furthermore, it was also a remarkable and radical work which tackled the idea of homosexuality within the Asian community in those times. To him, it is evident that community and identity politics are riddled with traps and paradoxes, tensions and contentions, but it is precisely the structural conundrum that has contributed to his fiction and films.

Enduring Legacy of Brave Writers

Three years before The Satanic Verses (1988), Kureishi’s screenplay, My Beautiful Laundrette, enraged fundamentalists. In an interview to Prospect magazine, he recalled that around 100 people would turn up every Friday in New York, and would hold demonstrations outside the cinema. One of them read: ‘No homosexuals in Pakistan.’

The watershed moment for Kureishi, however, was the fatwa that was issued against Salman Rushdie, after which he started researching fundamentalism.

“It changed the direction of my writing,” Kurieshi reportedly remarked. “Unlike Salman, I had never taken a real interest in Islam. I come from a Muslim family. But they were middle-class—intellectuals, journalists, writers—very anti-clerical. I was an atheist, like Salman, like many Asians of our generation were. I was interested in race, in identity, in mixture, but never in Islam. The fatwa changed all that.”

Once, one of the nurses at the National Health Service (NHS) mistook Kureishi for Rushdie. In a humorous anecdote, Kureishi recalled the moment.

“As the nurse flipped me over she asked me, “How long did it take you to write Midnight’s Children?’” To which, Kureishi replied, “If I had indeed written Midnight’s Children, don’t you think I would have gone private?”

Rushdie, who lost one hand and one eye in a vicious on-stage attack in 2022, has been writing to Kureishi regularly. The two writers happen to be old friends.

“My friend Salman Rushdie, one of the bravest men I know, a man who has stood up to the most evil form of Islamofascism, writes to me every single day, encouraging patience,” Kureishi mentioned in one of his dispatches. “He should know, he gives me courage.”

And while there is tremendous anguish around the world, they together are a poignant example of brave writers who endure.

Reviving the Best of What Twitter Could Be

For Kureishi, writing is everything. In an interview in 1996, he said, “I write really in order to keep myself alive. To interest myself. To find out what I think.”

Despite oscillating between moments of sadness and despair and between moments of raging creativity, he is determined to keep writing. In fact, according to his son Carlo, he is writing abundantly these days, despite his condition.

His tweets appear to be spontaneous, but Kureishi painstakingly plans them. The newsletters embody the most innate and primal purposes of literature: to survive and hold on to it.

“Every day when I dictate these thoughts, I open what is left of my broken body in order to try and reach you, to stop myself from dying inside.”

His writing is rife with irony and despair: mirroring the darkest realities of human lives.

His dispatches from an unfolding crisis is an extension of what he does best: narrating drama, musing over art, sharing painfully poignant anecdotes and reflecting on life, all with a touch of wit and sadness and humour and intimacy.

These posts are all part of what has evolved into a Twitter journal, in which he keeps his followers up to date on his progress in real time. His regular and unexpected posts reveal some intimate ideas on creativity, loss, anecdotes, coffees, and cunnilingus.

It is a voice without any illusions and pretence. Let us not lose sight of where we are though. His condition remains uncertain.

“I have no home now, no centre. I am stranger to myself. I don’t know who I am anymore. Someone new is emerging,” Kuresihi tweeted on January 13.

Meanwhile, he clings to himself, existence, hope, and, above all, wit.

(Kalrav Joshi is a multimedia journalist based in London. He writes on politics, democracy, culture, and technology. He tweets @kalravjoshi_.)