The last proverbial nail in the coffin was hammered in by Jagjivan Ram, the then deputy prime minister. He sent a letter to Prime Minister Morarji Desai listing the failures of the Janata Party government. The Lok Dal faction of the Janata Party led by Charan Singh and Raj Narain had already quit, leaving the government in a minority.

But Morarji Desai, always a stubborn man, insisted he would face a vote of no confidence in the Lok Sabha rather than resign. Following up on his letter, Ram met Desai personally and told him that even he will resign and quit the Janata Party.

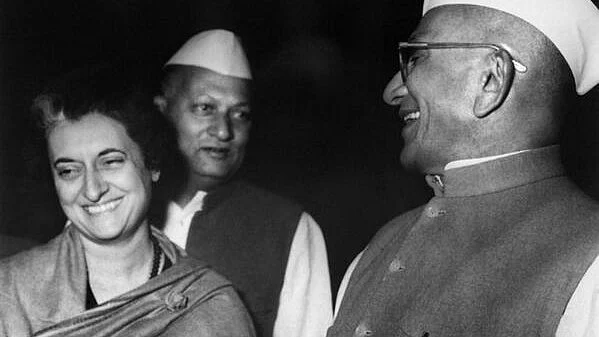

Finally, facing the inevitable, Morarji Desai submitted his resignation to President Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy on July 16, 1979. Indira Gandhi propped up a Charan Singh-led government for a few weeks before yanking support. In the elections that followed, Indira stormed back to power.

Ever since, the term “opposition unity”, or the lack of it, has become a source of constant debate, commentary, speculation, scorn, and hope.

A Visceral Dislike of the 'Authoritarian' Leader

Back in 1979, events showed that political parties with differing ideologies and vaunting ambitions of leaders can ride public anger against a ruling regime and cobble up a government. But that government that would sooner or later collapse like a pack of cards. Back then, the only glue that could bind disparate parties and leaders that constituted the Janata Party was a visceral dislike of the “authoritarian” Indira Gandhi. They wanted to “save democracy”.

In contemporary India, “opposition unity” is the talk of the town as 26 opposition parties have forged an alliance called I.N.D.I.A to “save democracy” when the Lok Sabha elections come calling in 2024.

The only glue that seems to bind the disparate parties and ambitious leaders is a visceral dislike of the “authoritarian” Narendra Modi. Back then, it is the Congress-led by Indira Gandhi that dominated the political landscape of India. Today, it is the BJP-led by Narendra Modi that dominates the same.

Can a “united opposition” defeat the Modi-led NDA in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections the way it ousted Indira Gandhi in 1977? And if it does, will it survive a full term of five years? What are the similarities between 1977 and a possible repeat in 2024? What are the differences?

Before we analyse the tantalising similarities and differences, here is a quick recap of what transpired before and after the 1977 Lok Sabha elections.

Recap: Formation of the Janata Party Government

In an earlier column in this series, we had argued it was economics more than politics that led Indira Gandhi to impose a state of Emergency in June 1975.

Virtually all opposition leaders were arrested and jailed. Habeas Corpus was suspended and in its most disgraceful moment in history, the Supreme Court caved in before the might of Indira Gandhi. The media was muzzled and silenced as censorship was rigidly enforced. As veteran leader L K Advani would famously remark later: When Indira Gandhi asked you to bend, you crawled. Inspiring exceptions apart, the media, like the Supreme Court did not really cover itself with glory. Since there was no social media in that era, news, information, and propaganda were disseminated via good, old-fashioned word of mouth.

In a move that surprised everyone, Indira Gandhi announced in early 1977 that she would lift the Emergency and call for fresh Lok Sabha elections. All opposition leaders were released from jail.

Anchored by Jayaprakash Narayan who had led nationwide protests against Indira Gandhi in the run-up to the Emergency, a bevy of leaders opposed to Indira Gandhi decided that a united opposition front was necessary to take on and defeat the seemingly invincible Indira Gandhi at the hustings.

The Janata Party was formed.

It was a strange concoction and mixture of disparate ideologies and ambitions. The CPI(M) agreed to form an alliance with the Janata Party but keep its separate identity to guarantee its “ideological purity”. At the other end of the spectrum, the Bhartiya Jan Sangh (which became the BJP in 1980 after the collapse of the Janata Party regime in July 1979) decided to leave ideology aside for the larger task of ousting Indira Gandhi. It subsumed its identity and became part of the new Janata Party. The Jan Sangh was joined by Bhartiya Lok Dal, a left-leaning socialist outfit led by Charan Singh.

The third element of the Janata Party were old Congress veterans led by Morarji Desai who had split with the Indira Gandhi faction of the Congress in 1969. Remember, there was no free speech and free media back then; nor any social media.

But politicians are much smarter than what journalists think of them. And it is this group that became the fourth element of the Janata Party. Congress leaders like Chandrasekhar, Jagjivan Ram, and H N Bahuguna left Indira Gandhi and joined the Janata Party. Commentators of that era recall how Indira Gandhi told her inner circle after hearing about the Bahuguna exit that she knew she would lose as Bahuguna was a master of gauging public perception.

Anyway, elections were held and the Janata Party won a massive majority. The easier task was to ride public anger over the Emergency and defeat Indira Gandhi.

Forming a government proved far more difficult.

Recap: Collapse of the Janata Party Government

There were three claimants to the post of Prime Minister: Morarji Desai, Charan Singh, and Jagjivan Ram. The lack of space prevents the authors from narrating the shenanigans of those days.

But after many suspense-filled days and often acrimonious arguments, Morarji Desai became the Prime Minister (Disclosure: the lead author is related to Nanaji Deshmukh who was involved in that process and even offered the post of deputy prime minister).

But neither Charan Singh nor Jagjivan Ram were satisfied and never really accepted Morarji Desai as their leader. The fractious government was constantly best by centrifugal forces. Being made deputy prime minister didn’t satisfy Charan Singh and Jagjivan Ram. The whole pack of cards collapsed in 1979.

Ostensibly, the reason was the demand by socialist leaders like Raj Narain (who had defeated Indira Gandhi from the Rae Bareilly seat in 1977) and George Fernandes that former members of the Jan Sangh must publicly move away from their ideological roots in the RSS. The real reasons were unbridled ambition, hubris, and a total inability to “live and let live” by the “opposition” leaders.

“Opposition Unity” proved to be a mirage.

Then and Now

What then is similar to events and the polity back then and now?

One big similarity is the visceral dislike of Narendra Modi like it was with Indira Gandhi back then. Add desperation to it. Many contemporary opposition leaders realise that political careers could be in deep peril if Narendra Modi wins a third consecutive Lok Sabha mandate; a feat not achieved even by Indira Gandhi. In the event, they are willing to bury egos and differences in their single-minded pursuit of “saving democracy” by ousting Modi.

The other similarity is that Modi towers over the political landscape just as Indira Gandhi did back then.

The third similarity is that like in 1977, an array of powerful opposition leaders and regional chieftains would be arrayed against a single leader.

But the similarities end there.

This looks more like the 1971 elections when Indira Gandhi made a pitch for her own singular leadership. Her famous campaign line “main kehti hoon ki garibi hatao, wo sab kehte hain ki Indira hatao” has an uncanny similarity with Modi’s current pitch of “Ek akela sab par bhari”.

How else do we understand the arithmetic and chemistry of Indian electoral contests?

Have we realised the Congress under Rahul Gandhi got the lowest number of possible seats in the 2014 and 2019 elections even though his number of votes was at par with the BJP under Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 1996 when the BJP became the single largest party in terms of seats in India? Or for that matter when the BJP in its first avatar post-Jan Sangh managed a paltry two Lok Sabha seats in 1984, even though it was the second largest party in India after Congress in terms of vote share?

In the famous gravity-defying victory of 2014, the BJP under Modi got 31 percent votes which were still 4 percent less than the 35 percent polled by Indira Gandhi in her worst possible election of 1977 rout caused by the famous Janata party post-emergency.

In electoral terms, she was carrying more votes at the rock bottom of her career in 1977 than the BJP’s best-ever performance by that time in the 2014 elections. And Modi’s best so far was 37.8 percent in the 2019 Lok Sabha, which is still three percent less than what the Congress managed to get in 1989 when we all understand that Bofors sunk the ship carrying Rajiv Gandhi.

But the Devil is in the Details

It was the opposition unity at the micro level which delivered magic in the 1967, 1977, and 1989 elections. It was the absence of the same that resulted in Congress sweeps in the first 5 decades after freedom. Without opposition unity in 1984, the BJP was limited to two Lok Sabha seats even with a country-wide vote share of 8 percent.

But in the presence of opposition unity, its tally shot up from two to 84 Lok Sabha seats, even though its vote share went up from 8 percent to only 11 percent in the 1989 elections.

The anti-Congress block of 40 percent votes polled in the 1977 post-Emergency, got split to approximately one-fourth to the BJP and three fourth to non-BJP opposition votes in the 1984 elections. We are keeping Communist parties out of the equation right now.

By the 1991 elections, this block of 40 percent votes got split 50/50 between the two blocks. By the 1998 elections the tables turned, and BJP got almost three-fourth of this opposition block, forcing the rejig of opposition parties. Most of them which voted against Vajpayee in the (in)famous 1 vote fall of his government formed after the 1998 elections, actually joined NDA before 1999 elections.

From that combination block of NDA in 1999 to 2019, the BJP has taken the pole position and is in the majority even without the allies. But that doesn’t mean they don’t need allies. It still needs allies to cross the 40 percent vote share mark, which by the way was the rock bottom of Rajiv Gandhi in the 1989 elections.

So, alliances do matter, but times have changed. The Congress is finding itself where BJP was in the early 90s and Modi is aiming for the numbers that Congress used to have in the 70s and the 80s.

The most obvious difference is the presence of noisy, raucous media and social media in contemporary India. Modi's critics do accuse him of muzzling the media and dissenting voices. But the tens of millions of social media posts criticising, mocking and even abusing Modi that spout every day demonstrate that his critics are exaggerating. No one could have dared write and speak such things about Indira Gandhi.

The second big difference is that the BJP doesn’t really dominate Indian politics the way Congress did back then. For instance, electorally, the BJP is virtually non-existent in states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh and is a marginal player in Telangana and Punjab.

The third major difference that could prove critical during the 2024 Lok Sabha elections is that voters are quite upset with the high prices of daily essentials including food items. But the authors are yet to see deep and simmering anger and rage of the kind that swept aside Indira Gandhi in 1977.

I.N.D.I.A can still defeat the NDA. But it is definitely not the favourite at the moment in the “Satta Bazaar”.

(Yashwant Deshmukh & Sutanu Guru work with CVoter Foundation. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)