(This story was first published on 13 December 2021 and has been republished from The Quint's archives in light of the Centre's decision to reduce disturbed areas under Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) 1958 in Nagaland, Assam, and Manipur.)

The 'mistaken' and 'regretted' assault carried out on civilians in Nagaland on 4 and 5 December by the Indian Army has been met with dismay and disbelief, as 14 locals lost their lives at the hand of the forces meant to protect them.

The killings predictably stoked public ire in the region, and brought into question the legal framework which is seen as allowing such a tragedy to occur.

The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) 1958 has motivated resistance ever since it was implemented in areas designated as 'disturbed'.

Here is a look at the controversial law – what it is, its history, and why there are calls by even state governments for its repeal.

Explained: The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) & Why it Inspires Dissent

1. What Happened in Nagaland?

On Saturday, 4 December a truck carrying eight villagers home from a coal mine in Nagaland's Tiru was ambushed by the Indian Army, who were at the site for an alleged counter-insurgency operation.

Six civilians died on the spot and two were critically injured. The army, expressing regret, described the incident as a case of 'mistaken identity.'

After hearing gunshots, several villagers arrived at the spot to find armed forces personnel allegedly trying to hide the bodies by wrapping up and loading them in another truck.

The violence that ensued between the anguished locals and the paramilitary personnel led to the death of seven more civilians.

Following the indiscriminate attack, 600-700 locals carrying sticks, stones and machetes barged into the camps of the Assam Rifles in retaliation, as per the police. Amidst the confrontation, another protesting citizen, and a jawan was gunned down.

Expand2. What is AFSPA: The Law & History

The foundational legislation for AFSPA was promulgated by the colonial British government in an attempt to stifle the Quit India movement in 1942. It was then titled the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Ordinance, 1942.

After Independence, at a time when the Partition had just hurled India into searing internal unrest, the ordinance was converted into an Act, which was initially only supposed to remain in force for a year, but was only repealed in 1957.

A few years into Independence, the government of India was faced with pockets of insurgency in the Naga district, along the borders of Burma. The resistance had taken a form of a fight for independence from the Indian state by 1954.

In light of these developments, on 11 September 1958, the AFSPA as we know it came into being, for dealing with situations in the northeastern states.

But what is AFSPA?

AFSPA allows for armed forces to be conferred with 'special powers', in any region designated as a 'disturbed area', either by the Centre or the Governor of a state or the Administrator of a Union Territory.

Section 3 of the Act says this power can be invoked when a part of a state/UT or even the whole state/UT "is in such a disturbed or dangerous condition that the use of armed forces in aid of the civil power is necessary".

Once an area has been designated as a 'disturbed area', the Act provides the armed forces with the following 'special powers':

To open fire or use force, even causing death, against any person in contravention to the law for the time being or carrying arms and ammunition;

To arrest any person without a warrant, on the basis of “reasonable suspicion" that they have committed or are about to commit a cognizable offence;

To enter and search any premises without a warrant;

To destroy fortified positions, shelters, structures used as hide-outs, training camps or as a place from which attacks are or likely to be launched.

These sweeping powers are augmented under Section 6 of the Act, which grants the personnel involved in such operations immunity from prosecution without sanction.

Section 6 notes, "no prosecution, suit or any other legal proceeding can be instituted, except with the previous sanction of the Central Government.."

Critics of the law argue that this amounts to a blanket immunity given the rarity with which sanction is granted, and leads to impunity for commission of human rights violations.

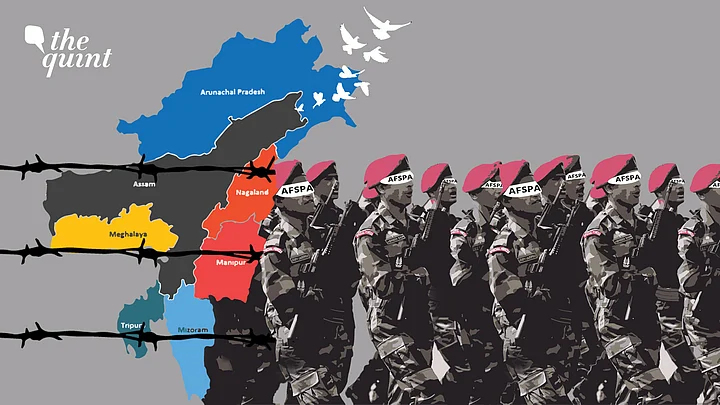

Expand3. The 'Disturbed Areas': Where Has AFSPA Been Imposed?

AFSPA covers all the northeastern states, even though it does not apply until a particular region is designated as a 'disturbed area'. At present, all of Nagaland and Assam have been notified as such, as has all of Manipur except the Imphal municipal area (though the notification for Manipur is set to expire in December 2021 unless reimposed).

In Arunachal Pradesh, the districts of Tirap, Changlang, and Longding, as well as the areas under the jurisdiction of the Namsai and Mahadevpur police stations (on the border of Assam) are currently notified as 'disturbed areas'.

The Act is not currently imposed in Mizoram, Tripura, and Meghalaya, all of which had been designated as 'disturbed areas' for long periods of time in the past.

A separate Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, on the same lines as the AFSPA of 1958, was enacted by Parliament in 1990 which also remains in force. Another similar law was invoked in Punjab in 1983 and remained in force during the militancy years, before being repealed in 1997.

Expand4. A Decades-Long Resistance

In AFSPA-imposed areas, citizens have long advocated for the revocation of the law, given its colonial legacy and the way in which its provisions have bred a culture of abuse, oppression, and immunity.

The history of this law is punctuated with atrocities and human rights abuses, the most recent of which are the excesses seen in Nagaland's Mon district.

Since the 1950s, the people of Nagaland and Mizoram have repeatedly alleged cases of indiscriminate air raids and bombings by the Indian military.

The provisions of the AFSPA do not include any safeguards for ensuring accountability for army personnel committing crimes, leading to rights activists echoing the concerns of locals time and again.

In the wake of instances of fake encounters, extrajudicial killings and massacres, the United Nations had taken note of the draconian law in 2012 and noted that AFSPA had "no role to play in a democracy."

This came seven years after a Centre-appointed committee headed by former Supreme Court judge BP Jeevan Reddy had recommended that it be repealed and any relevant provisions added to the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.

Despite upholding AFSPA in 1997, the Supreme Court also raised concerns about the law in 2016 and sought to clarify its usage.

In an important judgment on a plea by the Extra Judicial Execution Victim Families Association (EEVFAM), the apex court ruled that the Act cannot be said to 'provide blanket immunity' to army personnel amidst anti-insurgency missions, and that even in an area designated as a 'disturbed area', the forces can only utilise their special powers against targets that meet the criteria specified in the Act.

"If any death was unjustified, there is no blanket immunity available to the perpetrator(s) of the offence," the bench of Justices Madan B Lokur and UU Lalit held, adding that "No one can act with impunity particularly when there is a loss of an innocent life."

“If members of our armed forces are deployed and employed to kill citizens of our country on the mere allegation or suspicion that they are ‘enemy,’ not only the rule of law but our democracy would be in grave danger."

Supreme CourtThe petitioners had alleged that 1,528 incidents of extrajudicial executions had occurred in Manipur alone, and not one of them was inquired into. The court held that there needed to be thorough inquiries into each of these killings.

Expand5. 'Repeal AFSPA': A Renewed Spark

The Nagaland killings have acted as a stimulus to reinvigorate the movement against AFSPA, which most recently led to the Nagaland state government urging the Centre to revoke the law in the northeast.

Following an urgent meeting of the Nagaland Cabinet, Nagaland CM Neiphiu Rio asserted, "At today's state cabinet meeting, we decided to ask GoI to repeal AFSPA not only in Nagaland but Northeast (altogether)."

While calling for the revocation, Rio uttered that he is "hoping that justice is done." Earlier, the chief minister had expressed the demand for revocation in a tweet: "Nagaland and the Naga people have always opposed #AFSPA. It should be repealed."

In 2015, the Narendra Modi government had signed a peace accord with Naga insurgent group Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland (Isak-Muivah) - NSCN (IM), laying down terms of negotiations for a ceasefire.

However, the imposition of the Act has been subject to repeated extensions in the region.

The Chief Minister of Meghalaya, Conrad K Sangma, also called for the repeal of the law following the Mon incident.

Expand

What Happened in Nagaland?

On Saturday, 4 December a truck carrying eight villagers home from a coal mine in Nagaland's Tiru was ambushed by the Indian Army, who were at the site for an alleged counter-insurgency operation.

Six civilians died on the spot and two were critically injured. The army, expressing regret, described the incident as a case of 'mistaken identity.'

After hearing gunshots, several villagers arrived at the spot to find armed forces personnel allegedly trying to hide the bodies by wrapping up and loading them in another truck.

The violence that ensued between the anguished locals and the paramilitary personnel led to the death of seven more civilians.

Following the indiscriminate attack, 600-700 locals carrying sticks, stones and machetes barged into the camps of the Assam Rifles in retaliation, as per the police. Amidst the confrontation, another protesting citizen, and a jawan was gunned down.

What is AFSPA: The Law & History

The foundational legislation for AFSPA was promulgated by the colonial British government in an attempt to stifle the Quit India movement in 1942. It was then titled the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Ordinance, 1942.

After Independence, at a time when the Partition had just hurled India into searing internal unrest, the ordinance was converted into an Act, which was initially only supposed to remain in force for a year, but was only repealed in 1957.

A few years into Independence, the government of India was faced with pockets of insurgency in the Naga district, along the borders of Burma. The resistance had taken a form of a fight for independence from the Indian state by 1954.

In light of these developments, on 11 September 1958, the AFSPA as we know it came into being, for dealing with situations in the northeastern states.

But what is AFSPA?

AFSPA allows for armed forces to be conferred with 'special powers', in any region designated as a 'disturbed area', either by the Centre or the Governor of a state or the Administrator of a Union Territory.

Section 3 of the Act says this power can be invoked when a part of a state/UT or even the whole state/UT "is in such a disturbed or dangerous condition that the use of armed forces in aid of the civil power is necessary".

Once an area has been designated as a 'disturbed area', the Act provides the armed forces with the following 'special powers':

To open fire or use force, even causing death, against any person in contravention to the law for the time being or carrying arms and ammunition;

To arrest any person without a warrant, on the basis of “reasonable suspicion" that they have committed or are about to commit a cognizable offence;

To enter and search any premises without a warrant;

To destroy fortified positions, shelters, structures used as hide-outs, training camps or as a place from which attacks are or likely to be launched.

These sweeping powers are augmented under Section 6 of the Act, which grants the personnel involved in such operations immunity from prosecution without sanction.

Section 6 notes, "no prosecution, suit or any other legal proceeding can be instituted, except with the previous sanction of the Central Government.."

Critics of the law argue that this amounts to a blanket immunity given the rarity with which sanction is granted, and leads to impunity for commission of human rights violations.

The 'Disturbed Areas': Where Has AFSPA Been Imposed?

AFSPA covers all the northeastern states, even though it does not apply until a particular region is designated as a 'disturbed area'. At present, all of Nagaland and Assam have been notified as such, as has all of Manipur except the Imphal municipal area (though the notification for Manipur is set to expire in December 2021 unless reimposed).

In Arunachal Pradesh, the districts of Tirap, Changlang, and Longding, as well as the areas under the jurisdiction of the Namsai and Mahadevpur police stations (on the border of Assam) are currently notified as 'disturbed areas'.

The Act is not currently imposed in Mizoram, Tripura, and Meghalaya, all of which had been designated as 'disturbed areas' for long periods of time in the past.

A separate Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, on the same lines as the AFSPA of 1958, was enacted by Parliament in 1990 which also remains in force. Another similar law was invoked in Punjab in 1983 and remained in force during the militancy years, before being repealed in 1997.

A Decades-Long Resistance

In AFSPA-imposed areas, citizens have long advocated for the revocation of the law, given its colonial legacy and the way in which its provisions have bred a culture of abuse, oppression, and immunity.

The history of this law is punctuated with atrocities and human rights abuses, the most recent of which are the excesses seen in Nagaland's Mon district.

Since the 1950s, the people of Nagaland and Mizoram have repeatedly alleged cases of indiscriminate air raids and bombings by the Indian military.

The provisions of the AFSPA do not include any safeguards for ensuring accountability for army personnel committing crimes, leading to rights activists echoing the concerns of locals time and again.

In the wake of instances of fake encounters, extrajudicial killings and massacres, the United Nations had taken note of the draconian law in 2012 and noted that AFSPA had "no role to play in a democracy."

This came seven years after a Centre-appointed committee headed by former Supreme Court judge BP Jeevan Reddy had recommended that it be repealed and any relevant provisions added to the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.

Despite upholding AFSPA in 1997, the Supreme Court also raised concerns about the law in 2016 and sought to clarify its usage.

In an important judgment on a plea by the Extra Judicial Execution Victim Families Association (EEVFAM), the apex court ruled that the Act cannot be said to 'provide blanket immunity' to army personnel amidst anti-insurgency missions, and that even in an area designated as a 'disturbed area', the forces can only utilise their special powers against targets that meet the criteria specified in the Act.

"If any death was unjustified, there is no blanket immunity available to the perpetrator(s) of the offence," the bench of Justices Madan B Lokur and UU Lalit held, adding that "No one can act with impunity particularly when there is a loss of an innocent life."

“If members of our armed forces are deployed and employed to kill citizens of our country on the mere allegation or suspicion that they are ‘enemy,’ not only the rule of law but our democracy would be in grave danger."Supreme Court

The petitioners had alleged that 1,528 incidents of extrajudicial executions had occurred in Manipur alone, and not one of them was inquired into. The court held that there needed to be thorough inquiries into each of these killings.

'Repeal AFSPA': A Renewed Spark

The Nagaland killings have acted as a stimulus to reinvigorate the movement against AFSPA, which most recently led to the Nagaland state government urging the Centre to revoke the law in the northeast.

Following an urgent meeting of the Nagaland Cabinet, Nagaland CM Neiphiu Rio asserted, "At today's state cabinet meeting, we decided to ask GoI to repeal AFSPA not only in Nagaland but Northeast (altogether)."

While calling for the revocation, Rio uttered that he is "hoping that justice is done." Earlier, the chief minister had expressed the demand for revocation in a tweet: "Nagaland and the Naga people have always opposed #AFSPA. It should be repealed."

In 2015, the Narendra Modi government had signed a peace accord with Naga insurgent group Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland (Isak-Muivah) - NSCN (IM), laying down terms of negotiations for a ceasefire.

However, the imposition of the Act has been subject to repeated extensions in the region.

The Chief Minister of Meghalaya, Conrad K Sangma, also called for the repeal of the law following the Mon incident.