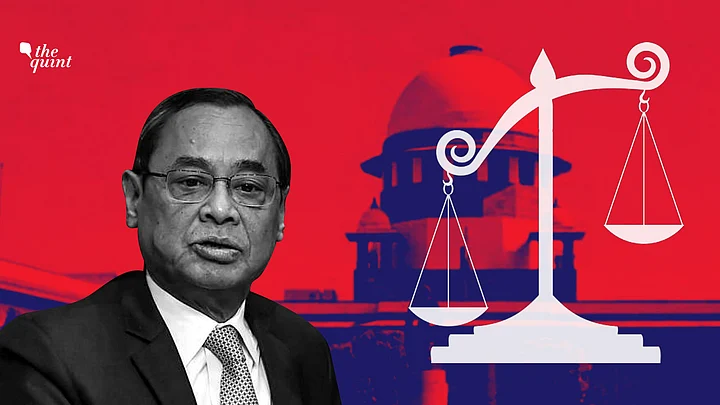

(On 16 March, President Ram Nath Kovind nominated former Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi to be a member of the Rajya Sabha – to be one of the 12 President’s nominees with special knowledge/practical experience. This article is being republished from The Quint’s archives in light of this development.)

When George Lucas announced a new ‘Star Wars’ trilogy in 1994, fans of the original were thrilled. To return to the galaxy they loved, with a chance for even better storytelling thanks to modern technology, their excitement reached fever pitch. And then in 1999, the first film in the ‘Star Wars’ prequel trilogy was released...

While fans expected ‘A New Hope’, they were handed ‘The Phantom Menace’. The title of the film was not the issue, but ask any ‘Star Wars’ fan and they’ll give you a laundry list of reasons why the film wasn’t what they’d been hoping for.

With the retirement of Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi on 17 November, concluding his 13-month tenure as CJI, fans of the Skywalker saga might find kindred spirits among those who are familiar with the developments in Supreme Court.

The Promise of the Judges’ Press Conference

On 12 January 2018, Justice Ranjan Gogoi (as he was at the time), was part of an unprecedented press conference by the four senior-most judges of the apex court, wherein they spoke about the threat posed to the independence of the judiciary and criticised the way in which the administration of the SC was taking place.

They specifically raised concerns about the manner in which important cases had been assigned by then CJI Dipak Misra and his predecessor, with matters of great significance placed before relatively ‘junior’ judges of the Supreme Court.

When the judges were asked by journalists present whether an example of this was the Judge Loya case – being heard at the time by a Bench headed by Justice Arun Mishra – Justice Gogoi had openly replied “Yes.”

The press conference sent the legal world into a tizzy. The four judges – Justices Gogoi, Jasti Chelameswar, Madan Lokur and Kurian Joseph – were criticised and lionised in equal measure for taking this revolutionary step.

Regardless of where one stood, this was clearly a brave move, breaking with the tradition of silence to which judges normally adhere. To most observers, this indicated that when Justice Gogoi became CJI (he was next in line according to the seniority convention), he would not shy from taking on the government’s attempts to interfere with the judiciary, and would stand up for the integrity of the institution, no matter what the personal cost.

In the twilight of CJI Dipak Misra’s controversial tenure, which would go on to include an attempt to impeach him, such qualities gave many who were worried about the institution, some much-needed hope.

A Complex Judicial Legacy

It is always a difficult task to describe the legacy of a judge when they retire. A common pitfall one falls prey to is to ascribe some sort of overarching theme to the judge’s pronouncements, to try to fit their verdicts into a narrative.

For instance, Justice Chelameswar was remembered for his dissents, so much so that some of the controversial judgments he wrote, like in the Rajbala case, were virtually forgotten when writing about him on his retirement in 2018.

CJI Gogoi’s judicial legacy is also a difficult one to pigeonhole.

Before he took on the highest judicial office, he had a reputation as a strict, no-nonsense judge, which he has maintained. Whether it’s refusing hearings when parties haven’t filed the right paperwork, chastising lawyers who don’t know the basic facts of their cases, or ensuring the labyrinthine Ayodhya hearings ran as per a strict timetable, he has ensured a degree of discipline in court that has been very welcome.

When he became CJI in October 2018, he spoke of his concerns over the pendency of cases in the courts, and said he had a plan to tackle the problem of delays in case hearings.

While he did set up a committee to look into these issues, and brought in restrictions on mentionings of cases in the Supreme Court itself – the crucial judicial reforms that were expected to unfold in his tenure haven’t got very far.

Justice Gogoi (23 April 2012-3 October 2018) showed a willingness to take on the establishment, shake things up, and dissent when he thought it necessary. Examples of this include:

- His dissent on whether Pranab Mukherjee’s election as President could be challenged in 2012– just months after he’d been elevated to the top court.

- His refusal to accept the Centre’s claims in 2017 that the Lokpal Act was unworkable, and that the Modi government needed to proceed with the appointment of the Lokpal.

- His reformation of the process to designate senior advocates in the apex court, bringing in an objective, points-based system, rather than the discretionary, often nepotistic manner in which this used to take place previously.

But when it comes to Chief Justice Gogoi (3 October 2018-17 November 2019), it is difficult to find such judgments. This is not to say that he didn’t deliver important verdicts, to be clear.

The decision in the Ayodhya title dispute will go down in history for putting to an end the longest-running saga in Indian legal history, one which had profound social and political implications, and getting this done was largely due to CJI Gogoi’s initiative and focus.

While one may disagree with various aspects of the judgment, it did at least avoid the mistakes made by the Allahabad High Court, locating its reasoning in law and evidence rather than belief and faith. Other observations in the judgment on following the 1991 Places of Worship Act might also be important in the years to come.

The judgment, confirming that the office of the CJI was subject to the Right to Information Act, was also a very important one and has far-reaching consequences (though he didn’t write the majority opinion himself) for transparency – even though it is subject to several restrictions.

Even so, CJI Gogoi’s tenure will not be remembered for important pronouncements on civil liberties, nor will it be remembered for judgments which took on the powers that be.

Doctrine of Sealed Cover & Deciding By Not Deciding

The concept of having information submitted to the court in a sealed cover was not invented by CJI Gogoi. However, this was never a regular practice in the courts before his time.

It began with the reports he used to have sent to him in the Assam National Register of Citizens (NRC) case – it should be remembered that the NRC exercise was not carried out at the behest of the government but on the basis of a judgment by him and Justice Rohinton Nariman in 2014, and was then managed and supervised by Justice and then CJI Gogoi along with other judges after.

In addition to the sealed cover usage, there are other questions that can be asked about CJI Gogoi’s handling of the NRC, from whether he should have recused himself as it affected him personally, to the manner in which it was pressed ahead despite numerous reports of problems with its compilation on the ground.

The sealed covers also found themselves at the controversial heart of the Rafale and Alok Verma cases, where the Central government sought to submit key details and information in this manner (meaning the parties to the cases never saw information that was vital to the eventual decision), and CJI Gogoi allowed their requests.

The Alok Verma case also saw a number of controversial adjournments, and a lot of time given to carry out investigations and inquiries into the former CBI Director’s conduct that were not particularly relevant to the case before the judges. Indeed, when the CJI-led Bench eventually reinstated Verma as CBI Director, one week before he was set to retire, the basis on which it made its decision had nothing to do with everything that had taken place over the two-plus months the case was heard.

By not deciding the case in time, the wrongfulness of the manner in which Verma was forced out of his position was not redressed – effectively deciding it in the government’s favour. The continuing delay in hearing the challenge to the electoral bonds scheme has had a similar effect.

Then of course there are the Kashmir cases at the court. The Centre abrogated Article 370 by way of Presidential Orders on 5 and 6 August, and imposed restrictions on movement and telecom services across the State.

Petitions were filed in the Supreme Court challenging these moves but CJI Gogoi did not take up any of these cases with urgency, which meant that the legality and constitutionality of the government’s actions were not examined and assessed even as they were making significant impact.

It wasn’t just the abrogation of Article 370 and the reorganisation of J&K into two Union Territories that was at stake. Civil liberties were infringed by the lockdown, and the detention of all public figures was questionable in law. But even habeas corpus petitions weren’t taken up swiftly, often being adjourned for two weeks at a time.

By the time CJI Gogoi finally decided to move these cases to another Bench which was not burdened with Ayodhya hearings, it was the end of September, and even now, over 100 days after it all began, the cases are nowhere near being decided and nor has any relief been granted.

A Judge in His Own Cause?

But perhaps what CJI Gogoi’s tenure will be remembered the longest for is the way in which allegations of sexual harassment against him were dealt with. Note that this isn’t about the allegations themselves, but about how they were addressed, and the propriety of CJI Gogoi’s own conduct in all of this.

In April 2019, he was accused of sexual harassment by a Supreme Court staffer who used to work in the library and then in his chambers at his residence. The morning the news broke on four websites, CJI Gogoi convened a special Bench to hear what was termed an urgent matter regarding a threat to the independence of the judiciary.

To everyone’s astonishment, the CJI included himself on the Bench using his power as Master of the Roster, and used this opportunity to defend himself and allege a conspiracy against him – raising obvious questions about misuse of power. He then had his name removed from the documents of the court about these extraordinary proceedings, and set up a new Bench headed by Justice Arun Mishra to probe the conspiracy against him.

The public narrative had been hijacked, refocused on the alleged conspiracy to frame CJI Gogoi. This was not just thanks to the comments of CJI Gogoi, but also the public stances on the issue taken by the Solicitor General and Attorney General of India, the Bar Council of India, and Cabinet minister Arun Jaitley – without any investigation or inquiry, one might add.

By the time the Justice Bobde panel was set up on the evening of 23 April to actually look into the complaint, the message from the establishment was clear: Not only would the allegations be doubted (as is woefully inevitable in such cases), the weight of the judiciary and the executive would be behind the accused, and conspiracy theories were more of a priority than the complaint.

Soon after the complainant withdrew from the inquiry proceedings citing the refusal to allow her a lawyer and give her copies of her statements as they were recorded, the panel gave CJI Gogoi a clean chit. The proceedings about the alleged conspiracy have not seen the light of day since the week they were announced, nearly seven months ago.

Addendum

‘Star Wars: The Phantom Menace’ was a disappointment for even the most ardent fans of the franchise. Some blamed the negative views on unrealistic expectations, but even from the most objective standpoint, it got a lot of things wrong.

The films that followed failed to improve things either. Even so, fans stuck with the series, and eventually, it was able to rise from the ashes in 2015 with a new set of films because it was always about something bigger, an idea that was greater than the sum of its parts.

What does this have to do with the office of the Chief Justice of India and the Supreme Court? That’s for you to decide.