Not Just Delhi: Data Reveals New Pollution Hotspots Emerging Across India

New pollution hotspots are emerging across India with barely any mitigation strategies in place, reports show.

advertisement

Every winter, Delhi takes the spotlight for its toxic air and dangerously poor AQI, but zoom out, and you'll find that several parts of India, especially across the north, are not far behind.

Recent studies have identified severe air pollution hotspots and airsheds in cities and districts across Assam, Bihar, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Tripura, Rajasthan, and West Bengal. Experts tell The Quint that although mitigation policies exist on paper, they are poorly implemented on the ground, with almost no monitoring systems to ensure compliance.

While Delhi’s pollution-control measures are endlessly debated, the other severely polluted regions rarely enter the conversation.

Not Just a Delhi Story

Delhi has consistently topped global lists of the world's most polluted cities for the past decade. A recent study by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) ranked Delhi as the most polluted Indian state, with an annual population-weighted PM2.5 level of 101 µg/m³—2.5 times India’s air-quality standard and 20 times the WHO guideline.

The study, released in November, also found that the Indo-Gangetic airshed remains the most polluted region in the country, consistently non-compliant during winter, summer, and the post-monsoon seasons.

Apart from Delhi, the study found that Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, and Chandigarh saw 100 percent of their districts exceed safe limits in all the seasons, except the monsoon.

Seasonal analysis of shifting airsheds shows how each region’s PM2.5 varies through the year.

(Photo source: CREA)

Another study by Climate Trends comparing AQI levels across major Indian cities found that none of the metros can be considered safe in terms of air quality.

The analysis showed that all 11 major Indian cities (Delhi, Lucknow, Varanasi, Ahmedabad, Pune, Kolkata, Chennai, Mumbai, Chandigarh, Vishakapatnam, Bengaluru) reported AQI readings above safe limits for most, or even all, of the past decade, with even the relatively less polluted metros frequently breaching recommended thresholds.

Lucknow, Varanasi, Ahmedabad, and Pune were among the cities that consistently recorded high AQI levels over the years.

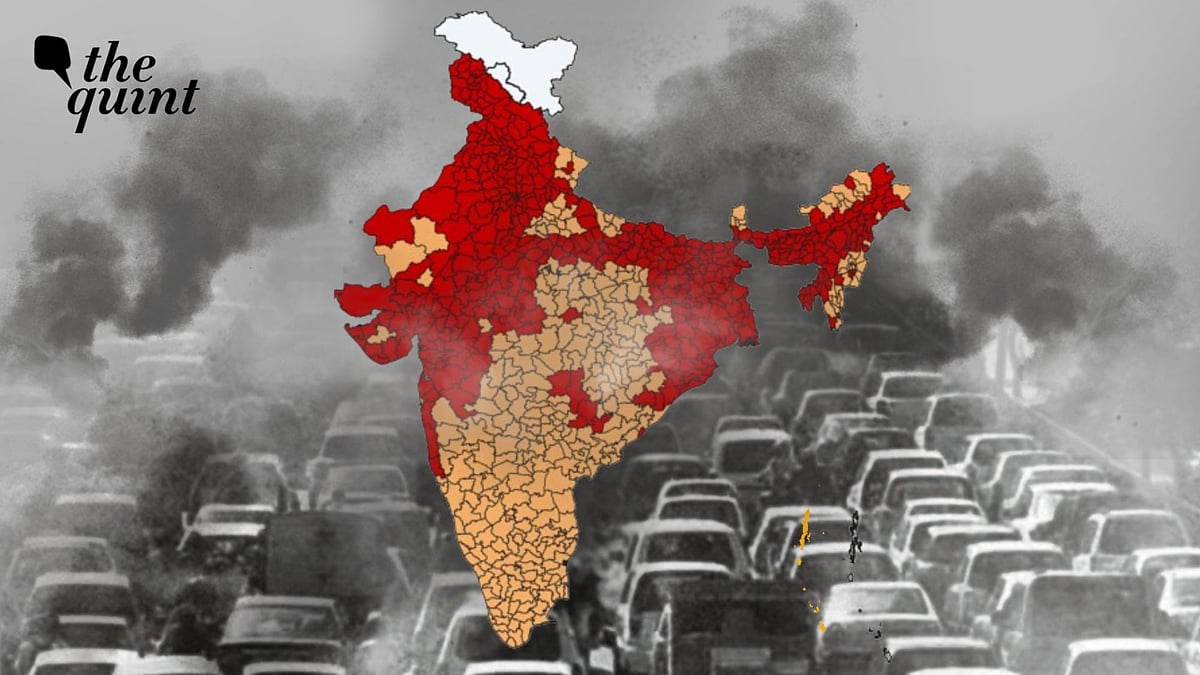

The following map shows the average annual PM2.5 levels across India’s districts using a satellite-based assessment by researchers at CREA. Notice how northern India has far higher concentrations than the south?

The annual compliance status of Indian districts on whether they meet NAAQS standards.

(Photo source: CREA)

This isn’t because North India has more industries or higher vehicular emissions than the South. “This has more to do with meteorology,” say experts.

"The meteorology in the South (since it is a peninsula) is more favourable for dispersion of polluted air, and so we see low levels (of air pollution)," explains Manoj Kumar, one of the authors of the CREA study.

However, he notes that this doesn’t imply South India is free from severe air-quality issues. "There are hotspots in South India, too. For instance, Manali, a highly industrialised area in Chennai, will surely appear on the list of the most polluted places this year or the next. But because we are looking at state and district level data, these hyperlocal hotspots generally get averaged out," explains Kumar.

Moreover, monitoring infrastructure in many parts of the country is weaker than in the tier 1 countries like Delhi, which creates the impression that those areas are less polluted. Delhi’s extensive monitoring makes its pollution more visible, but in places where air quality isn’t measured, pollution simply goes unrecorded, giving the false sense that the problem doesn’t exist.

Take Tripura, for instance. All eight monitored districts exceeded the NAAQS year-round, according to the CREA study that used satellite-based PM2.5 assessment. Yet, the entire state has only two official air-quality monitoring stations maintained jointly by the Central and the state governments, and, according to the CPCB website, one of them is currently inactive.

(The Quint has reached out to CAQM and CPCB with a detailed questionnaire on the inactive monitoring stations and their response to the studys' findings. We will incorporate their comments when we receive their response.)

New Hotspots Are Emerging

Another study published by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) on 1 December found that Delhi’s air-quality gains have plateaued over the past decade. The study also identified several new pollution hotspots within the city.

The study flagged Jahangirpuri, Bawana and Wazirpur, Anand Vihar, Mundka, Rohini, and Ashok Vihar as new hotspots. It also identified Vivek Vihar, Ashok Vihar, Nehru Nagar, Alipur, Sirifort, Dwarka Sector 8, and Patparganj as emerging hotspots, with most of these locations recording annual average PM2.5 levels above 100 µg/m³ between January and November this year.

Emerging hotspotes in Delhi NCR.

(Source: CSE report: Toxic cocktail of pollution during early winter in Delhi-NCR)

CREA's Manoj Kumar tells The Quint that the issue first came to attention when Byrnihat topped IQAir's 2024 ranking of the most polluted places on earth. Until then, most people had barely heard of this small industrial town on the Assam-Meghalaya border.

"We looked into what was happening here and found out that the Assam-Meghalaya border region has several industries concentrated here, many of which operate without pollution control norms," says Kumar.

The True Pollutors are Hidden in Plain Sight

While farm fires have long been blamed for North India’s winter pollution, experts underscore that mounting data points to year-round emissions, particularly from vehicles, industries, and construction, as major contributors to India’s toxic air. Further, winter spikes in Delhi-NCR are largely due to meteorological conditions that trap these pollutants.

For instance, according to a report by the International Energy Agency (IEA), road transport currently accounts for 20-30 percent of urban air pollution.

The CSE study, which focuses only on Delhi, also found that daily PM2.5 spikes are closely linked to traffic emissions, particularly NO₂ and CO during the busy morning (7-10 am) and evening (6-9 pm) hours, when winter air doesn’t disperse pollution easily.

"Now we have enough tools and data to tell us where the pollution is coming from and what the sources are," says Sunil Dahiya, founder and lead analyst, Envirocatalysts.

Data from Vahan Protal shows that Assam and Tripura, the two most polluted states in the Northeast, recorded a 37 percent increase in vehicle registrations in 2024 compared to 2021. Assam saw a 26.5 percent jump between 2022 and 2023 alone.

'Can't Outrun Toxic Air'

The evidence is increasingly clear that moving from one Indian city to another won't help you escape from polluted air.

So, what can be done?

“A sustained, long-term, science-based policy reform backed by genuine political will to take tough decisions,” answers Palak Balyan, Research Lead at Climate Trends.

At a high-level review meeting on Delhi-NCR air pollution, Union Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav directed authorities to fast-track the on-ground execution of decisions taken in earlier meetings. According to a press note released by the ministry on 2 December, he stressed strict, high-quality implementation of action plans across key areas, including road repair, dust control, Construction and Demolition waste management, industry compliance, smart traffic management, public transport expansion, legacy waste management, and greening of open spaces.

Yadav has also asked stakeholders to prepare detailed Annual Action Plans for the coming year, to control pollution generation at source, with time-bound execution of the plans to ensure proactive planning toward improving air quality in the NCR.

Right now, despite the rules in place to curb emissions from construction, industry, and even waste disposal, “enforcement agencies struggle to monitor violations or impose fines, and compliance with construction and industrial emission standards is often ignored,” Prof PK Joshi of JNU’s School of Environmental Sciences had told The Quint in an earlier conversation.

"Because constuction sites are widely dispersed, government departments do not have the capabilities or resources to inspect each and every site," adds Anumita Roychowdhury, Executive Director, Research and Advocacy at CSE.

The issue of implementation persists even in Delhi, where monitoring systems are relatively stronger. In most other states, where regulatory capacity is far weaker and enforcement mechanisms are minimal, the problem is even more acute.

Another major underlying factor for the enforcement gap, experts note, is the absence of reliable, publicly accessible data. Without it, meaningful implementation becomes nearly impossible.

And even when strategies are put in place, there is little to no monitoring of their implementation. “Take GRAP, for example," Kumar says, adding, "Can you prove it works? That it is being implemented properly or preventing air quality from worsening? There is no way to know. We don’t know what exactly is happening on the ground, and without data we cannot assess the impact of any action being taken.”

"Our air pollution policies and action plans have mostly been reactive in nature, including the National Clean Air Program. It came about in 2019 after we knew that this is now a major problem. We only started enforcing clean construction activities after the construction problem hit the roof. So we have to be better prepared. We have to anticipate what could happen," Swagata Dey, policy specialist and the air quality policy and outreach group at the think tank CSTEP tells The Quint.

The impact of this lack of preparedness is visible everywhere. “Right now, we don’t take strict action against institutional polluters, nor do we address systemic administrative failures like the lack of good public transport and mobility in our cities,” says Dahiya, adding,

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined