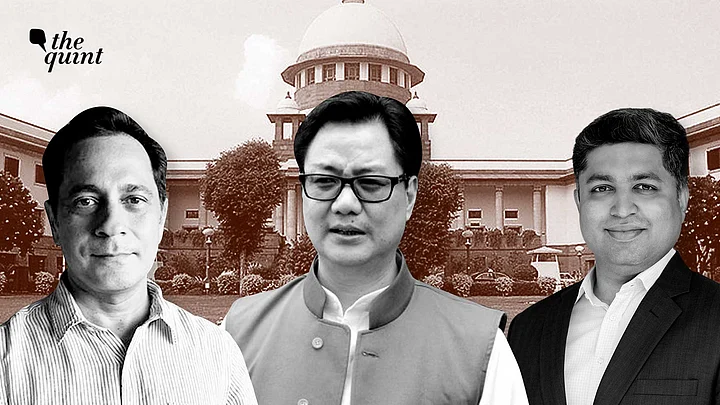

Does the decades-old Collegium system have any relevance in modern-day judiciary? This has been the most asked question from several quarters after Union Law Minister Kiren Rijiju took on the Supreme Court's process of appointment of judges in India.

Weighing in on the issue, Vikram Hegde—an Advocate on Record to the Supreme Court discusses the problems and solutions of the Collegium system and how the independence of the judiciary can be ascertained within the existing structure.

Courts have always been central to our constitutional scheme. In the last couple of decades, they have also come to occupy a prominent place in our discourse as well.

The reaction of the political executive to the increasing prominence of the judiciary has ranged between maintaining a respectful silence to vocalising some sharp questions on the functioning and, of late, the manner of appointment of judges. Recently, the Union Law Minister and even the Vice President of India have criticised what is known as the Collegium system of recommending judges to be appointed.

The process of appointment of judges in India is unique. No other country has a system of judges selecting judges—a fact that all the critics of the Collegium point out.

Collegium Enables Judiciary’s Autonomous Functioning

The Constitution of India does not expressly contemplate such a system. Indeed, such a system was not even in place for the first four decades of the functioning of our Constitution. Judges were to be appointed by the President. The President acting on the advice of the Union Council of Ministers was to make such an appointment only after consulting the Chief Justice of India(CJI)

In addition, the executive could consult other Supreme Court judges and High Courts as necessary. By a process of judicial interpretation, the requirement of “consultation” with the Chief Justice came to mean that the President would need the “concurrence” of the Chief Justice.

The Chief Justice would provide such concurrence not on their sole opinion but collectively as a group of other senior judges. This committee of Senior judges, initially numbered three, was then expanded in 1998 to five. This committee is known as the Collegium.

The putative successor of the incumbent Chief Justice is also a part of the Collegium, even if not among the four seniormost judges. Justice Sanjeev Khanna, who is likely to be the next Chief Justice of India, is not among the five senior most judges of the Supreme Court at present. Hence, the Collegium should presently consist of six members.

This mechanism does insulate the process of appointment of judges from political interference to some extent and helps maintain the independence of the judiciary.

Non-Partisan Approach of Indian Courts

It helps avoid a situation like in the USA where judges are identified by the party in power when they were elevated to the bench. Their decisions on contentious issues are often on partisan lines, thus, eroding the image of the Supreme Court as an independent institution guided by reason.

But such an insular mechanism is not without its pitfalls. There has long been criticism of the judiciary as a body with no periodic democratic approval, which often reverses the decisions of democratically elected governments. This criticism is amplified when even the appointment of the judges is not at the hands of the democratically elected government.

However, in every system of incumbents'-selected successors, there is a possibility of access bias creeping in. Several scholars and commentators have pointed out that the judiciary is lacking in diversity. The need for a broader representation on the Court has also been acknowledged by successive CJIs. The Collegium has also come in for some criticism for the opaque manner in which it functions.

For its part, the judiciary has complained that its recommendations are not acted upon by the government, or are acted upon in a selective manner. This amounts to a pocket veto of a Collegium recommendation.

How Selectivity and Delay Impact Lawyers’ Lives & Careers

The government has in some situations, justified returning the Collegium recommendations on the ground that it undertakes a process of vetting those recommended.

Whatever may be the reason, the delay in appointing judges recommended by the Collegium or even the return of such recommendations has deep implications for the persons involved. Eligible lawyers who are recommended by the Collegium, often curtail their practice with a sense of propriety.

They would also make significant changes in their personal lives. If they are left in limbo, or are denied the expected elevation, they are met with a major and pointless disruption in their lives. Examples of such disruption may even dissuade some competent persons from agreeing to be recommended.

With recent criticisms of the Collegium system building towards a crescendo, there is some speculation about a possible amendment to change this system. We may keep in mind that a constitutional amendment had been brought about last in 2014.

The proposed National Judicial Appointments Commission contemplated the participation of the law minister and two politically appointed eminent persons in the process of recommending judges to be appointed along with the three Senior-most judges. This amendment was set aside by the Supreme Court in 2015 as violative of the independence of the judiciary which is a part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

On considering the situation as a whole, while the Collegium system is not without its falls, there is no viable alternative on the table at present.

To read the view on Indian judiciary's collegium system, click here.