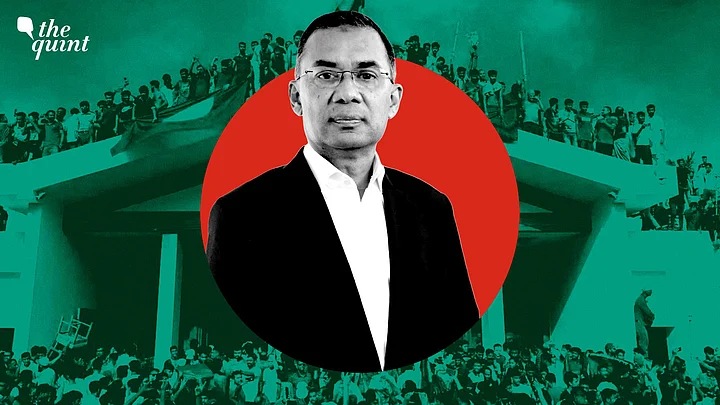

The Bangladesh general election, forced by the collapse of the Sheikh Hasina-led Awami League government in August 2024, has produced a decisive comeback for the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). It has gained two-thirds majority.

The dismal performance of the student-led National Citizens’ Party (NCP) shows yet again that while youth rebellions can trigger dramatic short-term change, they often do not deliver revolutionary transformation. Old actors often re-emerge to reshape the political order.

Seasoned Players Return to Bat

Its overwhelming majority has re-established the BNP as a dominant political force. This is a dramatic comeback after being marginalised and persecuted by the Awami League for nearly 15 years. This was expected as the Awami league was banned from contesting this election.

What was unexpected was that the Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI) did not get the “landslide victory” it had hoped for. While the party both managed to hold on to its traditional base and even expanded it somewhat, it could not significantly broaden its Islamist appeal despite fomenting communal tensions in the run-up to the vote.

Nor was the support base of the Awami League decimated despite the collapse of the Sheikh Hasina regime.

Many Awami League voters, however, seem to have shifted to the BNP rather than to the Jamaat. The positioning of the BNP as the only major moderate party in the fray, allowed it to appeal to those looking for a stable and inclusive government. The Jamaat remained tied to its Islamist identity, reducing its crossover appeal, especially among the minorities which felt safer with the BNP.

A pre-election survey had forecast that of the Awami League voters who wanted to vote in the election, 48 percent intended to vote for the BNP, about 30 percent leaned towards the Jamaat, 6.5 percent were inclined towards the NCP and 13 percent towards independents.

Reports after the voting confirmed this trend. Swing voters—including disaffected Awami league supporters—gravitated towards the BNP. Jamaat’s communal rhetoric also pushed minority voters towards the BNP. Female voters, fearful of the Jamaat, also seem to have opted for the BNP.

Still a large number of Awami League supporters seem to have chosen not to vote at all. This is reflected in the low overall voting percentage of 61 percent compared to mid-70s in a normal election. In Dhaka, many stayed at home—and the voter turnout in BNP leader Tarique Rahman’s constituency of Dhaka-17 was only about 32 percent.

Jamaat's Political Foray Stalled

The elections show that the Jamaat retains its ideological pull but lacks organisational capacity to run a national election campaign. Recognising this limitation, it fielded only 169 candidates, leaving the rest to its allies.

The ban on it in 2013 and years of political exclusion have left it unable to run an effective national campaign. Moreover, 1971 still resonates with the Bangladeshi people and the Jamaat still carries the baggage of collaboration with Pakistan during the Bangladesh liberation war.

However, the BNP will have to contend with the fact that the Jamaat has considerably improved its performance and that the more hardline Islamic Andolan Bangladesh has also made its debut in this election.

Islamist parties are gaining ground and by no means on the backfoot. Their future will depend on the BNP’s governance. Effective delivery will be necessary to blunt the Islamist tide as failure could facilitate it.

The NCP, a party rising out of the 2024 movement, won only about half a dozen seats. There are several factors for its dismal performance. The NCP retained only a skeletal version of the spirit of the July 2024 youth revolt. Most of its female members and other prominent leaders left the party because of its alliance with the Jamaat.

Further, many of its prominent leaders were from Chhatra Shibir, the student wing of the Jamaat. They quickly returned to their ideological parent, the Jamaat, once the Hasina government was toppled.

By the time elections took place, the spirit of the youth movement had dissipated, and the party was not drawing crowds. The NCP then decided to piggyback on the Jamaat after negotiations with the BNP failed.

The Jatiya Party that was once encouraged by some in India to become a flunkey of the Awami League, has drawn a blank in this election. The association with the Awami League has cost it dear.

What Lies Ahead for India?

One thing that is certain is that India-Bangladesh relations which had hit their nadir under the interim government of Muhammad Yunus will now be reassessed. Tarique Rahman has signalled a positive posture toward India.

The BNP’s manifesto prioritised trade and water-sharing cooperation. However, India should not expect overnight change. Public sentiment towards India has turned quite ugly over the past 15 years, and the BNP will need to balance that with pragmatic diplomacy.

It may adopt tougher stances on border security, especially killing by the Border Security Force, and water disputes (Teesta). Demands such as Hasina’s extradition will remain part of BNP’s nationalist narrative, even as it seeks long-term engagement.

The biggest challenge of the BNP will be implementing the 84-point reform programme (the “July Charter”) passed in the referendum held along with the general election. Some reforms are straightforward: reintroducing a caretaker government system can be achieved through constitutional amendment. Others will be harder. BNP has the numerical strength to legislate, but institutional inertia and entrenched interests will resist. Term limits on the prime minister and caretaker government reforms are easiest; judicial independence and anti-corruption may be difficult.

A Moment of Reckoning for Youth Rebellion

The 2026 election results have reaffirmed a recurring truth. While student-led movements are capable of protest mobilisation, calling strikes and running social media campaigns, they lack the organisational depth of established political parties. Without grassroot networks in the rural areas, they struggle against the established organisations of the older political parties.

Unlike the established political parties which are run by dynastic leaders, the youth parties have fewer publicly recognisable figures who command loyalty. They are unable, therefore, to convert their activism into sustained, reform-based governance.

Once a revolution succeeds, the older elites reassert themselves, pulling the political discourse into familiar patterns. The youth toppled the Awami League government but the old players, the BNP and Jamaat, have reclaimed political dominance.

(The writer is a senior journalist based in Delhi. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)