(This story was first published on 18 November 2022. It has been reposted from The Quint's archives to mark Mahatma Gandhi's birth anniversary.)

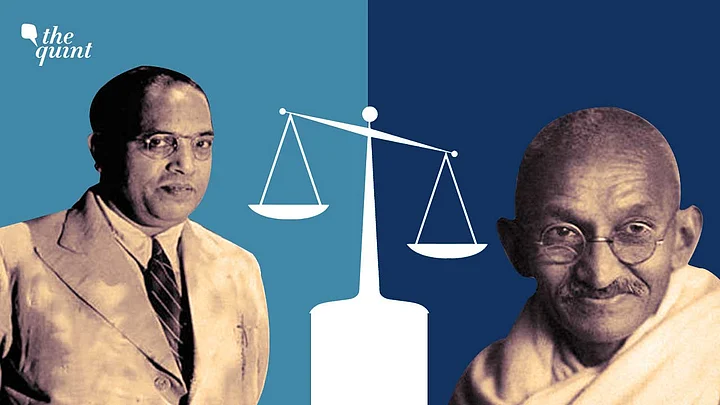

Babasaheb BR Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi represented the two ends of the political spectrum—particularly when it came to the social and economic questions facing the Indian society, which for Ambedkar, was marked with “graded inequality” of caste groups.

Graded inequality also means treating people as unequal beings based on their caste locations. Gifting the Indian Constitution to the people of India on 25 Nov 1949, his final speech representing the Committee entrusted to draft the Indian Constitution, Ambedkar spoke about this “graded inequality” of caste groups, governed by rules and rituals.

This speech can be of great value and context to read the consequences and implications of the recent Economically Weaker Section (EWS) judgement of the Supreme Court and what it means for justice in India. By justice, as we find in the Preamble of the India constitution, we mean social, economic, and political.

Hierarchy in Idea of Justice

The order of the three—social, economic, and political is significant and symbolic, not accidental. The importance of this order was also recently highlighted in a public lecture by P Sainath while inaugurating the Centre for Human Rights Studies at RV University where I teach.

That the social appears first before the two—economic and political—provides us with a clue to one of the central contradictions between Ambedkar and Gandhi on the question of social justice and destiny of modern India.

Freedom and justice compliment each other. Gandhi felt that political freedom should take primacy over the other two—social and economic, and that once, political freedom is achieved, we can easily address and attain economic and social freedom. But this choice of Gandhi of political over social is neither straightforward nor simple.

For Ambedkar, mind and soul’s emancipation “is a necessary preliminary for the political expansion of the people.” He argued that if power and domination in a society springs from social and religious domains, then reforming them becomes the first and necessary order.

The order of these three “social, economic and political” matters for social justice is hardly arbitrary. For him, putting political freedom first was also a tactic of the nationalist to de-politicise the social question and in this act, he charged Gandhi of being casteist in the guise of nationalism.

‘India: A Nation but Not a Society’

Without social freedom, the graded inequalities will continue to affect the minorities in India. Ambedkar had succinctly asked the Socialists in Annihilation of Caste: “Can you have economic reform without first bringing about a reform of the social order?”

This position of Ambedkar serves not just as a critique of the political man in Gandhi but also of the nationalist discourse in India which gave primacy to political freedom over social justice. Ambedkar, in this sense, belongs to the group of social reformers as Prathama Banerjee highlights in her recent, important work The Elementary Aspects of the Political.

For Ambedkar, the social question was the “first question of modern India," writes Banerjee. This India, Ambedkar argued, is perhaps a nation but not a society because after all, India is a ‘hierarchical network of caste communities sans sociability.

Ambedkar argued in Annihilation of Caste that sharing habits and customs, beliefs, and thoughts or mere physical proximity doesn’t guarantee society. His focus on social justice hardly needs any justification or qualification, for the life of a minority, even today, is marked by routine and spectacular violence in India. Caste, for him, is an ‘negative’, ‘old enemy’ of India and ‘anti-national’ for it generates jealousy and antipathy.

How the EWS Judgement Contradicts Social Justice

Reservations for minorities are safeguards to correct historic wrongs. It is meant to correct those social injuries that Indian social structure and society impose on its religious and linguistic minorities.

The EWS judgement which paves the path for reservation for socially non-minority groups based on economic criteria, will critically undermine the ethos of social justice in India— a society with a hierarchical social structure. This will pave the path to the persistence and solidification of graded inequalities by excluding the ST, SC and OBCs from its purview.

In his speech, he delivered while handing the constitution, Ambedkar had expressed multiple anxieties. First, was regarding India’s freedom itself and secondly, of India’s constitution. These anxieties were expressed with the misuse of freedom and the power the constitution will grant us, potentially paving the way to dictatorship.

One of the three things he mentioned to maintain democracy was an appeal to not be content with political democracy but instead, seek for social democracy. In order to have and maintain social democracy, Ambedkar opined, one has to recognise liberty, equality and fraternity as the principles of life and as an inseparable and interrelated trinity.

Ambedkar carefully outlined that “[]…there is a complete absence of two things in Indian Society”. The two absences he was referring to were of equality and fraternity. Continuing his speech, he said, “on the social plane, we have in India a society based on the principle of graded inequality.” Lack of mobility within caste groups shows us that liberty is an ideal at best, and we are far away from achieving it. If these issues weren't solved, he felt that both freedom and the constitution would be lost.

How will Ambedkar see the EWS judgement which has blown up the structure of political democracy? If not more, to our collective horror, his anxieties have come true. Decades of repair of Indian society and efforts and sacrifice of so many well-meaning individuals who fought for social justice have been undermined by this judgement.

Does the EWS Policy Secure the Socially Disadvantaged?

We all know that the “economic” criteria which has now become a primary criterion for reservation with EWS, will capture many other domains of education and employment. Furthermore, there is a danger of turning economic and social disabilities/backwardness as equal types of social inequalities which they are not. It will blunt the very idea of positive discrimination that seeks to grant upward social mobility and social justice. With this judgment, the very idea of justice, “social, economic and political,” is broken at its heart.

What is worse, that even as a policy, EWS is poor and doesn’t really address the issues of our economy. EWS doesn’t really increase the pie, in fact, the share of the pie gets smaller for the disadvantaged. It gives more room for the economically backward who otherwise command higher social status and rank.

This policy also diverts our attention from the real questions and the crisis that our economy is facing, characterised by joblessness and job losses. The real intervention will be to increase the pie—something that American political scientist Barrington Moore Jr. once noted.

The intervention in a crisis and with a growing population should be to increase social security and availability of goods and services. In other words, more hospitals, employment, scholarships, housing, schools, etc. If the government is really inclined to provide economic justice, increasing each segment of the economy should be the priority.

EWS is a graveyard of constitutional democracy in India and a “fresh injustice based on past disabilities” for the socially and educationally disadvantaged.

It is an anti-minority and anti-national judgement that goes against the ethos of justice and directive principles of our constitution. Any agreement to this judgement is casteist and essentially a legal promotion of social hierarchy in the name of economic justice. Furthermore, in the guise of economic justice for economically backward non-minority groups, there is an attempt to take political revenge on the real minorities and destroy the basis of social justice in India, which, without reservation for its absolute minorities, is a farce at best and a robust step forward towards an ideal Hindu rashtra.

To conclude with what Ambedkar said: “Turn in any direction you like, caste is the monster that crosses your path. You cannot have political reform, you cannot have economic reform, unless you kill this monster.” EWS breathes new life to this monster.

(Suraj Gogoi is an Assistant Professor in the School of Liberal Arts and Sciences at RV University, Bengaluru. The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not reflect or represent his institution. Further, The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the author's views.)