Appasaheb Kothule, 45, wants to sell two of his bulls. But he can’t. Qaleem Qureshi, 28, wishes he could buy bulls. But, he can’t do that either.

Kothule has been visiting various bazaars for over a month now. He has attended all the weekly markets held around Devgaon, his village, roughly 40 kilometres from Aurangabad city, in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra.

He tries his luck at the Adul marketplace. “My son is getting married and I need some money,” he says.

Nobody is willing to pay more than Rs 10,000 for the pair. I should get at least Rs 15,000 for them.Appasaheb Kothule, farmer from Marathwada region

Meanwhile, Qaleem Qureshi sits at his beef shop in Aurangabad’s Sillakhana area, mulling over ways to revive his dwindling trade.

I used to do business of Rs 20,000 a day (with earnings ranging from Rs 70-80,000 a month). Over the past two years, it has declined to a fourth of that.Qaleem Qureshi, beef shop owner, Aurangabad

Cattle: Insurance for Farmers

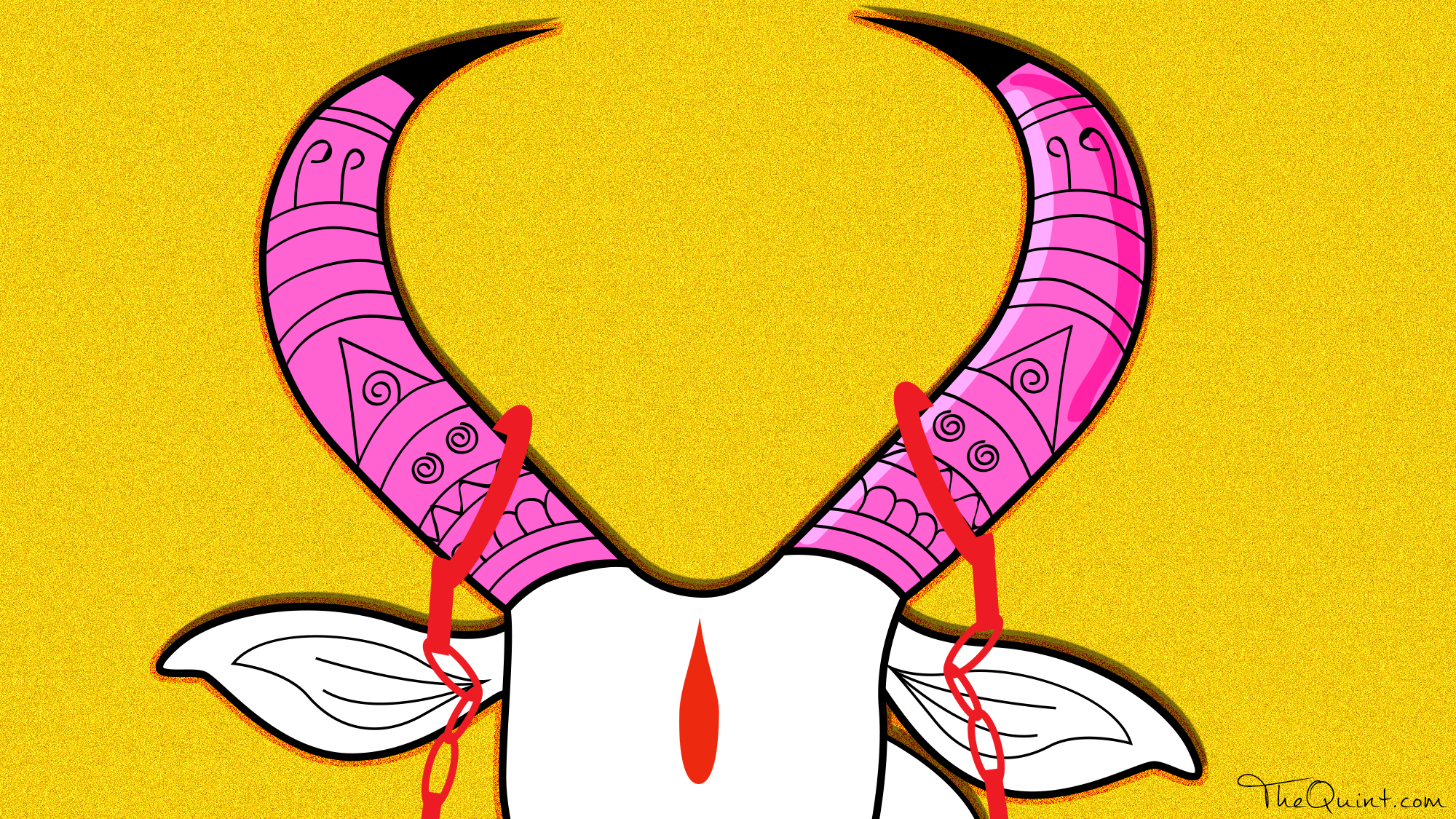

The beef ban in Maharashtra is a little over two years old. By the time Devendra Fadnavis of the Bharatiya Janata Party became the chief minister in 2014, the agrarian crisis had deepened under the previous Congress and Nationalist Congress Party regimes.

A lethal combination of rising input costs, fluctuating rates for crops, water mismanagement and other factors had set in motion widespread distress. As a result, tens of thousands of farmers committed suicide. Fadnavis managed to intensify the crisis by extending the prohibition of cow slaughter to bulls and bullocks in March 2015.

Also Read: Cattle Regulation to Hurt Rural Economy, Affect Marginal Farmers

The bovine is central to the rural economy and the ban has had a direct impact on businesses that depend on cattle. It has equally impacted farmers who, for decades, used the animals as insurance – they traded their livestock to raise instant capital for marriages, medicines, or an upcoming crop season.

Kothule, who has five acres of farmland where he cultivates cotton and wheat, says his finances have been hit by the ban. “These two bulls are only four years old,” he says, pointing to his tethered animals.

Any farmer would have swiftly bought them for Rs 25,000 a few years ago. Bulls can be used on farmlands until they are 10.Appasaheb Kothule, farmer from Marathwada region

Few Buyers for Cattle

But now, farmers are reluctant to buy cattle even though the prices have plummeted, knowing it will be difficult to get rid of them later. “I have spent a few thousand rupees in transporting the bulls from my home to various bazaars,” says Kothule.

Adul is four kilometres away, so I walked with my cattle. Other weekly bazaars are in a 25-kilometre radius, so I have to hire a bullock cart. I already have a debt burden. I need to sell these bulls.Appasaheb Kothule

As we talk, Kothule keeps a desperate eye out for buyers. He reached the market at 9am. It is now 1pm, and the sun is beating down on him. “I have not even had water since I reached,” he says, adding, “I cannot leave the bulls alone even for five minutes for fear of missing out on a customer”.

What Happened To the Cattle Shelters The Govt Promised?

Around him in the bustling maidan, with temperatures touching 45 degrees Celsius, various farmers are trying everything possible to crack a deal. Janardan Geete, 65, from Wakulni, 15 kilometres from Adul, is getting the horns of his robust bullocks sharpened to make them look more attractive. “I bought them for Rs 65,000,” says Geete. “I will be happy to settle for Rs 40,000.”

Kothule says the growing water shortage in Marathwada and rising fodder costs have made it more difficult to maintain livestock. Added to this is a lack of cow shelters.

When Fadnavis imposed the beef ban, he promised to establish shelters. Farmers were told they could donate their cattle to these shelters instead of bearing costs of maintaining animals that could no longer work on their farms. But the shelters have not materialised, dealing the farmers a double blow.

Farmers cannot raise money by selling their livestock and are stuck with the animals even after they become unproductive.

“How can we maintain our old livestock when we cannot even properly provide for our children? We spend Rs 1,000 per week on each animal’s water and fodder,” Kothule says.

Rural Economy Hit

Many others across the rural economic spectrum have been hit by the beef ban. Dalit leather workers, transporters, meat traders, those who make medicines from bones, have all been hit hard.

Before the ban, around 3,00,000 bulls were slaughtered in Maharashtra every year. Today, the slaughterhouses lie idle, while entire communities are battling economic distress. At Sillakhana, which hosts close to 10,000 Qureshis – a community that traditionally works as butchers and cattle traders – the impact is palpable. Qaleem has had to sack a few of his staff. “I have a family to feed,” he says. “What else could I do?”

“I used to make at least 500 rupees a day. Now I do odd jobs. The income is not guaranteed. There are days when I have no work,” says Anees Qureshi, 41, a loader in Sillakhana.

Also Read: Ban on Cattle Slaughter Is a Direct Attack on Right to Occupation

The beef ban has compounded the woes of the industry, which was already grappling with the growing agrarian crisis. People from villages began migrating in large numbers in search of work, resulting in a substantial dip in the local beef consumption levels, says Qaleem.

He says that his shop, which his family has owned since his great-grandfather’s time, is all he has. “Our community is not very well-educated (and cannot easily shift to other work),” he says. “We sell buffalo meat now. But people do not like it as much and the competition with other meat products is stiff.”

Beef forms a major part of the diet of the Qureshis, as well as various other communities, including the Dalits – it is a relatively cheap source of protein.

Replacing beef with chicken or mutton means spending three times the amount.Qaleem Qureshi

Mounting Debt

At the bazaar in Adul, Geete, who was sharpening the horns of his cattle, is one of few smiling faces. A farmer has agreed to buy his animals. Dyandeo Gore looks at him with envy. Gore has walked seven kilometres to Adul with his bull – the last of seven, which he sold over the years. His debt of around Rs 6 lakh has magnified in five years. By selling his last bull, he hopes to raise money ahead of the cropping season.

Nature does not support us. The government does not support us. Wealthy businessmen do not commit suicide. Debt-ridden farmers like me do. It is a daily misery. I do not know of a single farmer who wants his son to be a farmer.

The 60-year-old Gore goes from market to market, in the heat, on foot because he cannot afford transportation. “If I fail to sell him today, I will go to another bazaar on Thursday,” he says. “How far is that?” I ask him. “30 kilometres,” he says.

(The writer is special correspondent with LA Times. He can be reached at @parthpunter. This story was originally published on People's Archive of Rural India on 1 June 2017.)