In the old millennium, especially between late 1940s till the 1970s, we were told that the ‘gharelu ladki’ is the good girl and the other kind that dressed outlandishly and came back home late was the bad girl. The home is where the kitchen is. We idolized the brooding heart-broken lover or the sympathy-evoking metro tramp. The struggler is the one we were told to be like. No wonder our cinema reflected this.

And then when a filmmaker comes along and dusts away life’s worries, makes an unemployed hero hop-skip down valley greens, go chasing after women armed with back-packs of sunny melodies, clothes the leading ladies in sleeves tops and tight trousers, legitimizes their dancing the away in elite clubs to piquant scores, he is likely to titillate the unexpressed dreams. And when the same filmmaker keeps getting blamed for ‘rehashing’ the same formula successfully, his name is most likely to be Nasir Husain.

The title of Akshay Manwani’s book “Music, Masti, Modernity – The Cinema of Nasir Husain” itself is like a gleaming brass nameplate about the content within. Manwani traces Nasir Husain’s family background and establishes how the milieu of Bhopal/Lucknow that Husain grew up in shaped his thought process, including Husain’s age-old fondness for English literature and Urdu poetry.

Manwani also links Husain’s own impish and spendthrift boyhood to the profiles of heroes that that Husain chiseled out later. The book details out Husain’s formative days in the industry and the value gained in his apprenticeship at Filmistan, especially from his mentor and guide S Mukherji.

The book points out the nuances in character of Dev Anand as painted by Nasir Husain in Jab Pyar Kisise Hota Hai vis-à-vis the commonly known noir Dev Anand of Jaal and Baazi. Manwani delves deep into the characterization of the hero in each of Husain’s films right from Munimji, Paying Guest, the one-off Baharon ke Sapne, the “dual-track” heroes of Yaadon ki Baaraat, the dancing heroes of Tumsa Nahi Dekha, Hum Kisise Kum Nahin and the shifts to the contemporary youth in late 1980s demonstrating a sharp sense of observation as well as a comfort with the genre and language.

He underlines Husain’s re-casting of heroes into feather-light, carefree, musical young gents, shifting away the heavy-weighted serious ones, all the while plaiting along the genealogy and sources of inspirations.

Likewise the story tracks the modernity of the heroine whose frequenting of clubs and dance floors in modern attire (Pyar ka Mausam, Teesri Manzil) does not make her a fallen woman. The author confidently tables contrarian views by different people on the Husain heroine and layers them with his own views on how Nasir Husain created the modern, liberated day-to-evening girl like Sunita rather than creating the outlier superwoman like in Mehboob’s Mother India.

Manwani’s spots trends across films like the red sweater, the hero’s unsteady employment, the hill stations, the use of English dialogues at rather unexpected junctures, the inter-changing of ‘husn’ and ‘ishq’ in the signature couplet at the start of every NH film…. these once again speak of sharp observation.

The narrative of Music, Masti… also posits Nasir Husain’s bas-relief in the prevailing industry landscape; for example, the reasons for which the year 1957 was significant for the Bombay film industry– Husain’s directorial debut in Tumsa Nahi Dekha being merely one of them.

Manwani also strikes a balance in attributing to Husain the credit for ‘stylizing’ rather than for ‘patenting’ some of the milestone features in Husain films e.g. train songs with the hero outside the train or on its rooftop as opposed to the earlier train songs inside the locomotive. Manwani fittingly dedicates a chapter to the RD Burman-Nasir Husain partnership that lasted 20 years and acknowledges RD as one of the pillars of NH’s success run.

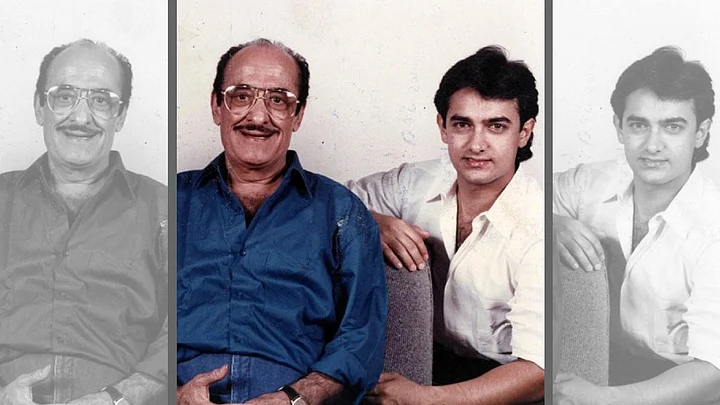

After the Burj Khalifaic success of three blockbusters of the 1970s, the unexpected fall and Husain’s resultant loss of self-confidence and withdrawing into a shell is told rather poignantly, showing his human frailty. And then the comeback as a family – father, son and nephew – in Qayamat se Qayamat Tak and Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar, the finale of a major cine award and the inevitable exit to an even sunnier world.

The book consists of extensive interviews and quotes from a diverse cross-section of people ranging from film historians, journalists to Nasir Husain’s family members (including Aamir Khan and Mansoor Khan), actors etc, underlining the extent of research done. It also contains behind-the-scene trivia on how certain scenes were shot, the camera angles, the heat generated within the studio, the “Wills” cigarette ad, the balloon-flight etc. It is easy to read and despite the analyses, does not slow down the reading pace. Intendedly or otherwise, the book flows like a Husain film.

One would have wished for the following insights in the book which are missing (especially given that music was one of Nasir Husain’s strengths):

- Why did Nasir Husain shift back and forth from OP Nayyar in Tumsa Nahi Dekha to Usha Khanna in Dil Deke Dekho and then back to OP and then to Shankar-Jaikishen?

- Why did Kishore Kumar never feature as a key singer in NH’s scheme of things? Even post Rafi’s demise, one never saw Kishore as the lead male singer.

A few other observations:

The musical success of Khazanchi (1941) has been proffered as the reason for the old-guard studio system breaking up. This is debatable. The studio system broke-up with people beginning to leave one of the biggest studios - New Theatres, Calcutta in the early 1940s. Another trigger was Ashok Kumar signing up for a film outside of the Himanshu Rai-owned Bombay Talkies in 1943.

At times, the statements sound repetitive. One specific example - two adjacent chapters titled “Phir Wohi Dil Laya Hoon” and “Sar Par Topi, Girls on Trees...” could have been clubbed for better punch.

Also, one feels that Nasir Husain has been oversold as a success factor in Munimji and Paying Guest in which he was the co-dialogue writer and scenarist/dialogue writer respectively. These films were made by Subodh Mukherji. Conversely speaking, why would a lion’s share of Caravan’s success not be attributed to Sachin Bhowmick who wrote the screenplay for the film? Here is where the biographer takes control from the author. Also, the episode of Vijay Anand being asked to direct Baharon Ke Sapne initially and then being asked to take control of Teesri Manzil instead is debatable as the timelines don’t match. Baharon Ke Sapne commenced months after Teesri Manzil did.

But, by and large, Akshay Manwani has remained objective and unbiased throughout. One agrees with Manwani that Nasir Husain, because of his sunny-side-up movies may never feature alongside the serious and social-message laden ones. But if movies are about elegant entertainment garnished with subtle messages, then the Nasir Husain recipe is the taste that lingers…

And “Music, Masti, Modernity – The Cinema of Nasir Husain” is a good, tangy appetizer.

(Balaji Vittal is the co-author (along with Anirudha Bhattacharjee) of the President's Gold Medal Award winning book "RD Burman: The Man, The Music" and "Gaata Rahe Mera Dil - 50 Classic Hindi Film Songs" which won the Best Book Award at MAMI 2015)