(Spoilers for Laapataa Ladies but also, why haven't you watched it yet?)

“This is my friend Deepak Kumar. He was returning home with his bride last night and lost her on the way,” laments a man sitting in a police station. The cop replies, “I've tried for years but I can't seem to lose her.”

It plays out like the typical husband-wife jokes on WhatsApp – a staple of the patriarchal society we live in. Who doesn’t remember the ‘biwi aur mobile main kya farak hai?’ (What’s the difference between a wife and a mobile phone) jibes?

This scene from Laapataa Ladies is enough to illustrate what stood out to me the most about the film – its dialogues.

The film is fiercely feminist in a way that makes you listen. Oftentimes, feminism is either treated as a dirty word in Indian cinema or it’s spelled out without any actual effort at nuance.

It’s all well and good to have characters yell, “Smash the patriarchy!” but films like Laapataa Ladies take a deeper, more incisive, look into the world women live in.

But First, Some Context

Two newlywed couples are travelling on a train – the main talking point during the journey is the dowry they received. The nonchalant way the discussion happens is telling in itself, but so is the way one of the mothers-in-law points out that her son’s suit is better to signify that that somehow makes them better.

While one of the grooms is making a hasty exit, the brides get ‘exchanged’.

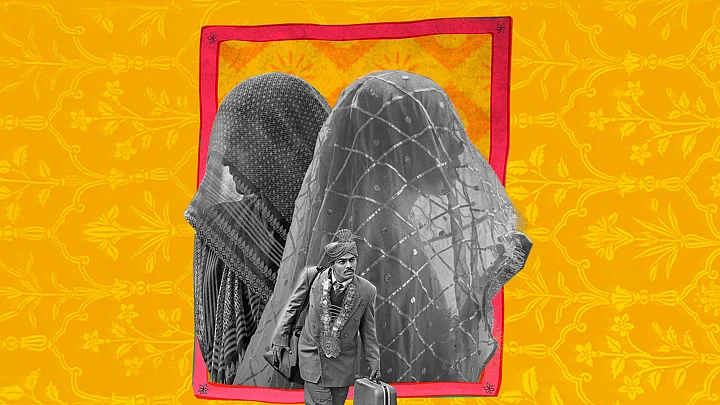

One of my favourite scenes from the film follows – as the duo travel to his village, there’s a shot through the woman’s veil. We see how the only things she can see clearly are her feet and the ground right in front of her. She has no way of knowing where she’s going or who she is going with. Her entire identity too is hidden.

The two brides in question are Phool and Jaya – both starkly different people. At Deepak’s house, Jaya starts a quiet revolution of sorts, and she does that simply by asking questions. When her sister-in-law says she doesn’t draw anymore, Jaya asks why. When she says she doesn’t have anyone to talk to because her husband isn’t in town, Jaya simply says, “Talk to me”.

'My Husband Isn't Here, Who Do I Talk to?'

For the longest time, Jaya's sister-in-law doesn’t speak in the film. Jaya is seemingly the first person to actually try to find out why.

"Bablu ke papa yahan hai nahi, baat kisse karenge hum? (My husband isn’t here, who will I talk to?)" she asks. Her identity in the house is tied to her husband – in his absence, talking to anybody else wouldn’t be ‘proper’.

This mentality is something that contributes to the isolation women feel. In that same vein, this idea actively discourages female companionship and solidarity. It is unjustly believed that it is the woman’s ‘duty’ to make sure all the chores in the house are done – if she goes out to meet her friends or family, she will be asked, “Ghar ka kaam kaun karega? (Who will do the work around the house?)”

Even beyond that, a woman socialising is often frowned upon – she must remain meek and submissive; someone who can easily shrink into the background.

Women are rarely able to build support systems for themselves for this same reason – who do they turn to? Laapataa Ladies doesn’t necessarily spell any of this out, but the subtext is clear.

That’s perhaps why it is especially heartwarming to see Deepak’s mother turn to her mother-in-law and ask, “Do you think we could be friends too?” only to be greeted with a hearty ‘yes’. This idea of a mother-in-law and daughter-in-law always being at odds with each other is deeply rooted in patriarchy as well. Sometimes it's generational trauma manifesting as internalised patriarchy – and other times it’s a result of society constantly pitting women against each other.

And at every turn, there’s more to Jaya than meets the eye – for instance, she has a knack for farming as well. When she offers a suggestion to save their crops, Deepak’s family doesn’t instantly shoot her down or mansplain their way out of it. They take her seriously.

Of Feminism, Family, and the 'Lonely Cat Lady'

Then there’s Phool – ‘abandoned’ by her husband, she wanders at a random train station. After spending a night in the washroom, she meets a man who takes her to Manju mai (Chhaya Kadam).

Manju mai is a character social media trolls would call the ‘lonely cat lady’ – except (like everyone else who gets that tag), she’s anything but. Manju is content with the life she has built for herself and her grief stems from her past more than her present.

With Manju’s story, Laapataa Ladies touches upon domestic violence and the need for agency.

Manju, having left an abusive marriage, now runs a tea stall near the station. She is much less hopeful about Deepak’s return than Phool.

One thing I often hear feminists say is, “We stand on the shoulders of giants”. In Laapataa Ladies, this phrase is realised through Phool and Manju’s equation. Phool is convinced that her mother trained her well with all the skills except, as Manju points out, these are skills she needs to be an ‘ideal wife’. While she can sustain herself inside a house, she was never taught how to survive outside those four walls. Phool can’t even name the town her husband is from.

While Jaya is trying to fulfill her dreams, Phool is attempting to regain agency over her own life. This ‘agency’ permeates the entire film.

Often people say that feminism is attacking the ‘family’ though that couldn’t be farther from the truth. Instead, the basic tenets of feminism question the status quo. They question why patriarchy pushes people into gender roles without giving them an actual choice.

What if a man wants to stay back home while his partner goes out and earns? What if a woman doesn’t want to take the lion’s share of the household chores and instead wants to earn for her family? What if a couple decides to split their tasks and responsibilities 50-50?

Everything boils down to the matter of ‘choice’ and Laapataa Ladies presents this idea through the opening premise – marriage.

The film doesn’t insinuate that Phool hates the idea of marriage just because she has regained her agency – the only thing that changes is that she realises that a marriage must be an equal partnership. She realises that she is ‘allowed’ to have a life outside of her husband and his family. Wanting to stay with Deepak is her choice. On the other hand, rejecting marriage and wanting to pursue a career is Jaya’s choice. Neither is presented as being superior to the other.

'Are We Going to Start Making Dishes Women Like Now?'

Over and over again, Laapaata Ladies talks about the need for female companionship and individuality. The film makes you wonder how many times we view women as recipients of care instead of caregivers. When Jaya suggests to Deepak’s mother that she should cook a dish she loves, the latter finds the idea incredulous. This brings me to my favourite dialogue from the film (distressingly so), “Ab kya auroton ke pasand ka khaana banega? (Are we going to start making dishes women like now?)”, she asks with a laugh.

So often I’ve watched women toil away, cooking for their families and making dishes their loved ones like but rarely have I seen them pick a dish they do. We say that ‘women work 24*7’ but do we actually think about what that means? Do we ever take stock of women’s needs, let alone attempt to fulfill them?

The idea of women taking care of people around them is so ingrained in us that we tend to forget that the people around them also owe them the same grace.

This is evident even in the way Deepak's mother asks, "Khaane ki taareef kaun karta hai?" Despite the fact that she has perhaps been cooking for the family for years, Jaya is the first person to appreciate her cooking skills. We have multiple (too many I would say) shows centered purely around cooking as a skill - how do we as people sit and 'ooh' and 'aah' at Masterchef dishes but forget to appreciate the food we eat at home?

But Laapataa Ladies’ social concerns extend to the men as well, specifically Deepak. He is visibly distraught about being separated from Phool – and can’t wrap his head around the fact that nobody else seems to be equally affected. People are more concerned about what Phool’s disappearance says about Deepak’s masculinity. His friends ask him why he can’t just ‘replace Phool with Jaya’ which leads to a massive argument.

'Just Kidding'

A discussion between Deepak and his friends is an astute exploration of privilege. When Phool is alone at the station, anyone who understands how the world works would feel a lingering sense of dread. Allow me to digress for a second. In the Janhvi Kapoor-starrer Mili, Mili is trapped in a freezer and doesn’t make it home at night. Instantly, her character is questioned – the police ask if she’s run away with someone. The sheer amount of danger she could be in pales in comparison to the need to prove she’s ‘moral’ and consequentially ‘worth’ looking for.

Similarly, while we know Phool is safe, people back at Deepak’s village don’t. And yet, Deepak’s friends theorise about what could’ve happened to her – the possibility of sexual violence is implied only for them to wonder if Deepak should even continue looking for her in that case.

As Deepak rages, his friends say they were ‘just joking’. A very real and harrowing possibility becomes a ‘joke’ because they have the privilege to do so; a privilege that is also granted to them by a patriarchal society.

As the film comes to a close, someone tells Jaya, “Don’t apologise for having a dream”. It feels a little on the nose but it’s just as important to hear, especially considering how omnipresent guilt is in women’s lives – the guilt of deciding to balance motherhood and a professional career, the guilt of putting themselves first, the guilt of choosing to not marry or have children, or the guilt of simply making their desires known.

When you watch a film like Laapataa Ladies, the premise can feel so simple – and that is exactly why a film like it is important. It’s important to see characters like Phool, Jaya, Manju, and Deepak on screen – to remind us that when oppression is omnipresent, revolution becomes necessary. And the subtle language of feminism in Laapataa Ladies does just that.