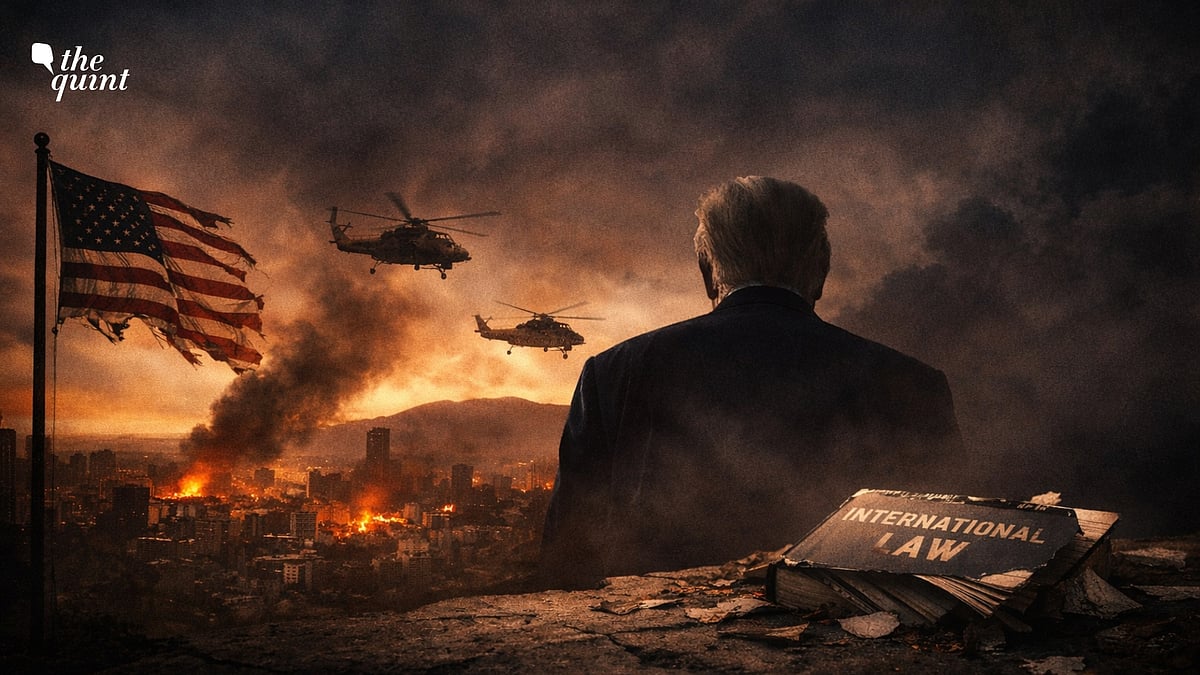

End of American Pretence: How Trump Shred International Law in Venezuela

The “Donroe doctrine” has unfolded an exercise of naked power to keep the West under American dominance.

advertisement

There is a curious coincidence in Donald Trump describing the events of Saturday, 3 December as “an extraordinary military operation in the capital of Venezuela.” On 24 February 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin termed his action against Ukraine as “a special military operation.”

Both probably wanted to play down their blatant violation of the sovereignty of another country—Russia sought to annex Ukraine, while the US now says that it will be "running" Venezuela for the foreseeable future. The New York Times has had no hesitation in calling Trump’s actions as “latter-day imperialism”.

Imperialism Rebranded as Order

The consequences of Putin’s actions in Ukraine are there for all to see—hundreds of thousands of people killed and large areas of Ukraine devastated. The effects of the American invasion will unfold in the coming period. Hopefully, they will not be as devastating, but you can be sure they will be equally consequential. For one, they have already helped bury the Western vanity that the world runs under the “international rule of law.”

Trump has said that the US “will run the country” and he even declared that the US is not afraid to put boots on ground. But his hopes seemed to be centered on Venezuelan Vice-President Delcy Rodrigues who Trump claimed would cooperate with the US.

From Monroe to ‘Donroe’ Doctrine

Trump has ascribed his actions to the 19th century "Monroe Doctrine". But that was aimed at preventing the further colonisation of the Americas by European countries. What has been termed as the "Donroe Doctrine" instead has unfolded an exercise of naked American power to keep the Western Hemisphere under American dominance.

Further, the kidnapping of a head of state violates a major principle of customary international law that gives substantial immunity to them. This immunity is recognised by the US Supreme Court, going back to an 1812 opinion.

Illegitimacy Is Not a License to Invade

Let’s be clear, the Maduro regime was illegitimate, despotic, and corrupt, and had forced millions of Venezuelans into exile. But that does not give the US any right to replace it by one of its choosing. Such a principle would undermine the basic principle of international law—sovereignty of states which is a basic principle of international practice and law.

The UN views state sovereignty as its basic founding principle and under Article 2(1) of its charter it is committed to the “sovereign equality of all its members”; and Article 2(4) says states cannot use force on the sovereign territory of another country without its consent, except for self-defence and then, too, with UN consent.

What If the Tables Were Turned?

Surely, it would mean that if the US expects that it can “arrest” the head of another sovereign state under its domestic laws, that same privilege should be available to those countries to conduct a similar action against a US president for, say, war crimes in Afghanistan and Iraq. And just what example is the US setting to China which is preparing its military to seize Taiwan which is not even a state under international law?

The US Constitution is clear that the Congress must approve of any act of war. Over time, presidents have pushed this boundary but none so blatantly as Trump. Debates in Congress, or for that matter a parliament, are crucial for the functioning of a democracy. A debate in the Congress would have showed up the flimsy nature of the Trump administration’s justification for its actions.

Narco-Terrorism: A Selective Outrage

Take the issue of narco-terrorism. This is a bit rich coming from an administration that recently pardoned Juan Orlando Hernandez, former president of Honduras from where he had run a major drug operation between 2014-2022.

Follow the Oil

Maduro does not figure in the report, and the only reference to Venezuela is to the Tren De Aragua a somewhat minor gang founded in a state in the north-central part of the country. In his press conference, Trump said that Maduro was the boss of the Cartel de Los Soles which does not figure in the report at all.

Why the US did what it did is staring us in the face: oil. A good old-fashioned imperial venture that once motivated policy in the Middle East, is back in America’s reckoning. Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves in the world amounting to 303 billion barrels. At its peak, the country produced 3.2 million barrels per day (bpd), current production is down to 1 million bpd.

Now Trump has announced that the US would operate and control the Venezuelan oil industry “until such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition,” adding at another point that “we’re going to take back the oil that, frankly, we shoulda taken back a long time ago.”

Global Stakes, Global Companies

Incidentally, the Venezuelan industry may be owned by the government, but a number of companies, including the ONGC Videsh, are working there through joint ventures. These include American-owned Chevron which accounts for a significant proportion of Venezuela’s output. Chevron works under a special license, which was renewed by the Trump Administration in December. Among the other companies are TotalEnergies of France, Repsol of Spain, Eni SpA of Italy, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) and so on.

Unlike the Afghan or Iraq invasion, the US has for once spelt out what it plans for the day after. But the idea—of running a large nation and presumably transitioning it to a democracy—is outlandish and could well end up in the same way that the US’ other 21st century regime-change ventures led it to.

(The writer is a Distinguished Fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. This is an opinion piece and all views expressed are the author's own. The Quint does not endorse or is responsible for it in any way.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined