The recent attack on Bangladesh’s iconic national monument ‘Dhanmondi 32’ — the house where the nation’s founding father, ‘Bangabandhu’ Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, lived and died — has left many within and beyond Bangladesh with a sense of foreboding. On 5-6 February, the building, which also housed the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum, was allegedly vandalised and torched by a mob.

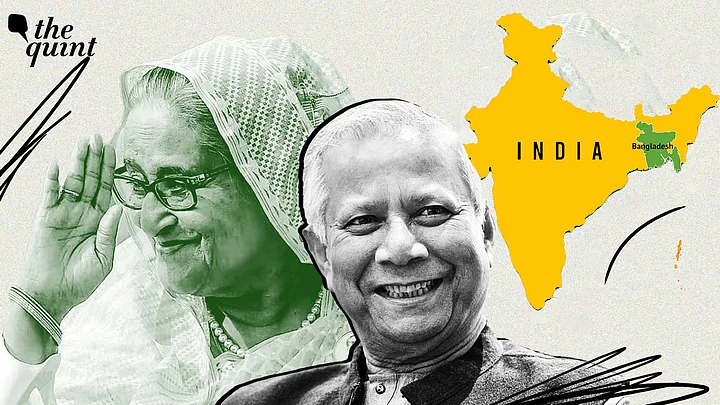

As striking images of the demolition spread, news of further attacks on buildings associated with Rahman and his followers, as well as Sheikh Hasina, the ousted leader of Bangladesh and Rahman's daughter, surfaced. The message seemed to be clear. The Bangladesh that Rahman and his followers envisaged and built would no longer be celebrated. Or even allowed to exist.

The apparent rise of conservative forces garbed as political opposition in Bangladesh since Hasina’s departure has raised concerns both within the country and India, its biggest neighbour with which it shares a long and porous border.

The clampdown on dissenters and Hasina supporters is evident in the arrests and persecution of Awami League leaders, attacks on their homes and associated properties, and detention of artists and journalists like Shahriar Kabir, who had advocated for punishment for war crimes against humanity committed during the 1971 Liberation War.

More recently, poet and essayist Sohel Hasan Galib was allegedly arrested by police, as per local news reports, on undefined charges. Earlier this year, former Bangladeshi journalist Farzana Rupa who, along with her husband and fellow-journalist Shakil Ahmed, is facing murder charges over the death of a protester last year, sought justice in court, accusing the authorities of "harassing" journalists by implicating them in murder cases.

Such trends could be the foretelling of shifts in South Asian geopolitics, already on the churn following US President Donald Trump's re-election.

Hasina’s supporters and many experts in India believe she was thrown out of power by a conspiracy hatched by the US in collusion with her opponents. The possibility of her conservative political opponents using the students’ protests as an opportunity to springboard a more militant and violent movement against Hasina cannot be ruled out.

However, independent observers say it was the growing resentment of her opponents and the general people that led to her overthrow.

Hasina claimed she fled the country to escape an assassination attempt that her long-time rival and head of the current interim government, Mohammed Yunus, masterminded. The Bangladeshi government has since reacted to the statements she made in India, cautioning that such statements were evoking a sharp reaction from some in Bangladesh.

From Hasina to Yunus

In her tenure, Hasina was credited with turning Bangladesh into a stable and fast-growing economy in Asia. The social indices of Bangladesh made impressive progress and women’s participation in different professions, including in the security forces and the army, increased significantly.

The leader nevertheless possessed an authoritarian tendency, and in her rule, the space for opposition and dissent shrank alarmingly. Several charges of extra-judicial killing and illegal confinement of detractors by her are now coming to the surface. From 2018 onwards, Hasina was accused of manipulating elections and unleashing her security forces and armed supporters to turn verdicts at the ballot in her favour.

The US had imposed sanctions on her for democratic backsliding and forced her to hold free elections. Though Hasina managed to win the 2024 election that was boycotted by the Opposition, she faced a major crisis soon after in July when a peaceful student protest turned violent and a number of protesters died in police firing.

The rivalry between Hasina and Yunus dates back to 2007 when he started showing political ambitions after his success at the Grameen Bank — and his microcredit policy received global attention. Hasina resisted the move, accusing Yunus of being an interloper imposed by the Americans. As Prime Minister, Hasina had filed a number of cases against Yunus for labour law violations and other offences when he headed the Grameen Bank.

Yunus, a globally renowned economist, was brought to head the interim government to put the economy on a growth track and stabilise the country in the throes of Hasina’s departure. So far, he has failed to improve the situation. Inflation has reached 10 percent and prices of food and other essential items have remained high. The near collapse of the law-and-order situation and the rising crime rate have alarmed people both within and outside the country.

The arms that were looted from police stations during the anti-Hasina protests are yet to be recovered and are in wide circulation among criminal gangs. The police, used by Hasina to suppress the protest, are discredited and lose all trust and confidence of the people. They are unable to assert authority against criminals.

The lack of stability has affected investors’ confidence in Bangladesh and Trump’s policy of withholding developmental assistance has added to the economic woes. Yunus has called for a reform of the country’s political and economic structures to repair the damage done by Hasina’s government.

Several committees have been formed to reform various aspects of the government like political, judicial, economic, finance and banking, security and police. Yunus has announced that elections will be held after the reforms. This has put him in direct confrontation with political parties, like the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the second largest party in the country after Awami League.

The BNP has been out of power for more than 16 years and is keen to return to running the country. The party’s leaders feel that in the absence of Hasina, the party has a strong chance of forming the next government. It has been pressuring Yunus to hold early elections and leave the implementation of reforms to an elected government.

Politics of Polarisation: Then and Now

Some feel Yunus is delaying the election to give the student leaders time to prepare and launch their own political party that can put up a stiff challenge to the BNP. However, in the face of sustained pressure, Yunus has announced that elections will be held by the year's end. Observers feel the forthcoming election will be one of the most polarised elections in Bangladesh between the secularists and the conservatives which might jeopardise the secular aspects of the Bangaleshi Constitution, a legacy of Mujib.

The 1972 Constitution has democracy, secularism, socialism, and nationalism as its basic tenets and was passed with overwhelming support after wide consultation with all political parties. However, the Jamaat and other conservatives who collaborated with Pakistan and opposed the creation of Bangladesh were excluded from consultations.

Mujib had a long history of confrontation with the Jamaat that began when he was in the forefront of the “Bhasa Andolon” (language movement) of the 1950s. The success of Bengali’s inclusion as a national language was the first victory of Bengali nationalism in a Punjabi-dominated, Urdu-speaking Pakistan.

The Jamaat opposed the liberation movement that led to Bangladesh’s creation from Pakistan in 1971 — a struggle that received India’s blessings and support. On the other hand, Mujib was also accused of turning into a dictator soon after. In 1975, he launched the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL), a political platform that observers described as a “political front and dictatorship” to marginalise his critics. In August that year, Mujib and most of his family were killed by a group of army majors. Hasina and her younger sister managed to escape the attack since they were visiting Germany with her husband. She was given refuge in New Delhi and stayed there for six years before returning to Bangladesh to start her political life.

Hasina hanged many Jamaat leaders for “war crimes” as well as some of her father’s assassins. She had kept the so-called ‘Islamist’ groups under check, though her methods were often questioned by human rights groups. In her absence, there is now a steady rise of conservative forces, who are setting the political agenda.

This has started worrying even Hasina’s critics. Three student leaders of the ‘July protests’ who are in the interim administration as key advisors to Yunus are believed to have affiliations with prominent conservative groups like the Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI) and the Islami Andolon (IA).

Student leaders who have been relentless in their attack against Mujib and Hasina have demanded a new Constitution to replace the 1972 Constitution, a move that has been opposed by most political parties.

While the Yunus government justified the demolition of Mujib’s residence as people’s reaction to the “wild allegations” made by Hasina in India, the government’s failure to stop the vandalism has led many to question Yunus' ties with the conservatives. Moreover, controversial moves like the countrywide drive called “Operation Devil Hunt” by the interim government to weed out "criminals" have further been seen by political observers as moves targering Awami League supporters.

The Jamaat and other conservative parties have held several meetings in recent months to form a broad coalition to push for an Islamic State in Bangladesh.

Many in the country fear that in the zeal to erase the legacy of Mujib’s regime, his critics may end up jeopardising (or supporting forces that want to change or modify) the secular character of the Bangladesh Constitution.

Regional Fallout: India, Pakistan

Hasina’s loss has been a big setback for India’s regional geopolitics. She was a dream partner for India and under her rule, the two sides saw the most cooperative period in Indo-Bangladesh relations, something that significantly increased since the Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government came to power. There was cooperation on projects for mutual benefit and there was a promise of enhanced connectivity for a wider market and investment and to bring India’s Northeastern states closer to the mainland.

On the other hand, Pakistan, which had been marginalised for long under Awami League governments but tried to return to mainstream under non-Awami regimes, may stand to benefit from the pro-conservative shifts in Bangladeshi politics. Though the country is currently facing a prolonged political and economic crisis and busy dealing with extremism in Balochistan, India fears it can come back if pro-Pakistan conservatives dictate the moves in Dhaka.

India wants stability in Bangladesh. Since Myanmar is already facing violence and unrest that has already affected Manipur and other states, India does not want a similar situation in Bangladesh. The porous border between the two countries can pose a security challenge for India if there is instability in Bangladesh. Delhi is worried about attacks on Hindus in Bangladesh as this can start an exodus of people to India. It has tried to reassure Dhaka that Delhi wants a cooperative relationship with Bangladesh.

Provocative commentaries from the two sides on social media have, however, led to a tense situation and will continue to affect normalisation of bilateral ties. India hopes an elected government in Bangladesh can start serious and sustained engagement that can benefit both. Meanwhile, it will try to maintain a cordial and working relation with the interim government of Yunus.

Hasina’s presence in India, however, is likely to be a sore point between the two sides. Even as the relentless hounding of Hasina's supporters in Dhaka may fuel further statements from the ousted leader, her outbursts will continue to strain ties between India and Bangladesh.

A big question remains on Hasina as the jury is still out about her future and relevance of the Awami League in Bangladesh. But as the euphoria about the July protests dies down and the anti-Hasina sentiments fade, any future government’s failure can help rebuild a positive image of Hasina. Whether it will be strong enough to pave the way for her return will remain a matter of speculation for a long time. But there is no doubt that the coming months will be crucial for Bangladesh as it can indicate the direction the world’s fourth largest Muslim country is headed for.

(Pranay Sharma is a commentator on political and foreign policy-related developments for over four decades. He has held senior editorial positions in leading media organisations and now works as an independent writer. This is an opinion piece. The views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)