“I think I made the mistake of going to the courts. First, the Supreme Court let us down, and now the sessions court has let us down. I think they don’t want to give justice to families of victims of Uphaar tragedy. Courts are not for ordinary citizens. I am shocked by what happened today."

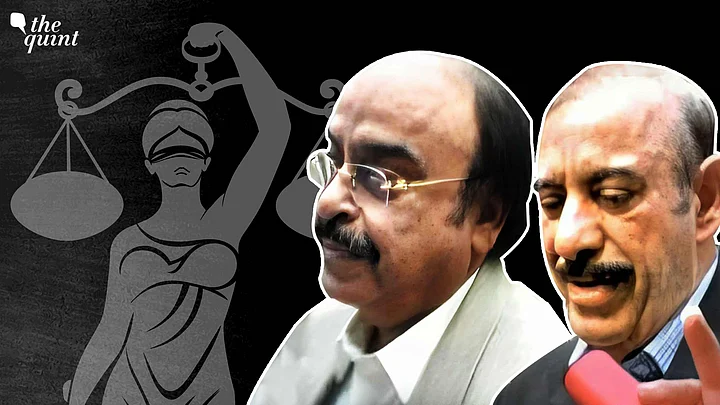

It is difficult to disagree with Neelam Krishnamoorthy, who lost her two children in the Uphaar fire tragedy back in 1997, when she said these words just after a Delhi court last week reduced the sentences imposed on Sushil and Gopal Ansal in the evidence tampering case against them.

The two had been sentenced to seven years' imprisonment and fined Rs 1 crore each by the trial court back in October 2021, after they'd been convicted under Sections 201 (evidence tampering) and 409 (criminal breach of trust by a public servant) of the IPC read with Section 120B (criminal conspiracy).

The case arose after it was discovered in 2002 that the Ansals had conspired with a judicial officer to tamper with the evidence against them in the main case over the deaths of 59 people in the Uphaar fire tragedy.

The convicts filed an appeal against their conviction and sentence. While sessions judge Dharmesh Sharma upheld the convictions and the fines imposed on them, he reduced their jail time to the amount of time they had already spent in custody (ie, 8 months).

For the Association of Victims of Uphaar Tragedy (AVUT), of which Krishnamoorthy is chairperson, this was a bitter blow to their quest for justice against the Ansals, who had only been charged and convicted in the main case regarding the fire in the cinema under Section 304A of the IPC (causing death by negligence), rather than any of the more serious offences.

The two had originally been sentenced to two years' imprisonment in that case, which had been reduced to one year by the Delhi High Court. The Supreme Court allowed Sushil Ansal to end his imprisonment three months early due to his age and ailments, while Gopal Ansal had to spend the full year.

While both were still required to pay a substantial fine (Rs 30 crore each) to fund a trauma centre in Delhi, the court's verdict had nonetheless seemed a bit of an exceptionally lucky break for the Ansals, who had not only not been charged with a serious offence, but not even been made to go through the full punishment possible for the lesser one.

The new decision by the sessions judge on 19 July means that the two businessmen, who had not only played fast and loose with fire safety in their cinema hall but also tried to destroy the evidence of their misdeeds, spent an even shorter time in jail – even though the maximum punishment the court could have awarded them this time was much higher.

While it is not incorrect for a court to consider relevant mitigating factors when imposing a sentence on an accused – old age and serious medical ailments are valid mitigating factors – the decision of the court is extremely questionable on law. Here's why.

A Strange Understanding of Double Jeopardy

As mentioned earlier, there were two main offences that the Ansals and their conspirators were charged with: Sections 201 (evidence tampering) and 409 (criminal breach of trust by a public servant) of the IPC.

The conspiracy involved both these offences, as a public servant was induced to commit criminal breach of trust, so as to tamper with the evidence.

The sessions judge does appear to have got it right in reducing the Ansals' sentence for the evidence tampering charge.

According to Section 201, if the maximum punishment for the offence in connection with which evidence was tampered, is less than ten years' imprisonment, then the punishment for tampering with the evidence can be up to one-fourth the punishment for the original offence.

The Ansals had sought to tamper with the evidence in the case against them under Section 304A of the IPC. The maximum punishment for this offence is 2 years, and so the maximum punishment that could be imposed under the Section 201 charge was six months' imprisonment – the trial court had imposed a three year jail term.

Reducing the sentence of the Ansals to time already spent in this regard was, therefore, understandable and correct in law.

Unfortunately, this makes a lot less sense when dealing with the other offence they were convicted of: conspiracy to commit criminal breach of trust by a public servant.

Under Section 409 of the IPC, the punishment for criminal breach of trust by a public servant is life imprisonment (it's ten years if a banker or other private agent). This means that the punishment for conspiracy towards this is also life imprisonment.

That was what was on the table for the Ansals in this case. The trial court which passed the original order of sentence did not have the power to pass an order for life imprisonment, and picked a fairly reasonable sentence of seven years' imprisonment instead.

While the judge's reasons to reduce the sentence for the offence of evidence tampering under Section 201 of the IPC make sense, the reasoning employed to say that a reduced sentence for the offence of conspiracy to get a public servant to commit criminal breach of trust is nothing short of bizarre.

Here's what the judge writes in para 24 of the order:

"Now, though Section 409 of the IPC is visited with maximum punishment up to the life or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, the proportionality test in criminal jurisprudence applied in the instant case by no stretch of imagination could be such applied in manner so as to make the appellants Sushil Ansal and Gopal Ansal suffer greater punishment for what they have actually served for commission of offences in the main Uphaar Case, since that would be in the realm of “double jeopardy”. What can not be directly, can not be enforced indirectly by the Prosecution since that course of action would be patently unconstitutional."

What the judge is saying is that the punishment that the Ansals are to be given for criminal breach of trust in connection with the main Uphaar case (ie, where they were convicted for death by negligence under Section 304A of the IPC) cannot be more than the punishment they received for the main Uphaar case, because that would amount to 'double jeopardy'.

Unfortunately, there is no legal basis for this proposition.

"Double jeopardy is a principle in criminal law which means that if a person has been put on trial for a particular offence and then convicted or acquitted, they cannot be put on trial for the same offence again," explains senior advocate Vikas Pahwa, who represented the AVUT in the case.

"But the two cases here are separate, and arise out of a different set of facts. The first case was about the negligence and issues related to the fire tragedy itself, while the second case was about their attempts to destroy evidence against them. As a result, the principle of double jeopardy will not be applicable."

While Pahwa did represent the victims' association in this case, he is absolutely right, as any definition of double jeopardy in case law or even a legal dictionary would confirm.

The sessions judge complains that the trial court appears to be looking to punish the convicts for the main Uphaar fire tragedy, but ironically he is the one who wrongly conflates the two cases, and completely fails to understand one of the basic rules of criminal law.

There is no legal principle that the punishment for an offence arising out of actions in connection with earlier offence has to be less than the the punishment for the original offence.

That only applies in the case of the evidence tampering charge, not across the board. Given the second offence was getting a judicial officer to commit criminal breach of trust and help engage in tampering with evidence before the courts is, quite obviously, an incredibly serious offence, and needs to be treated with an appropriate degree of seriousness, which the sessions judge failed to do.

Delay, Age & Illness Are Mitigating Factors – But to What Extent?

The sessions judge also looked at mitigating factors which have to be considered when deciding the sentence, and finds that the lower court had failed to consider these properly in this case.

He notes that "there is substance in the plea raised by the learned Counsels for the appellants that the impugned order on sentence has left out just, fair and humane considerations while awarding the impugned sentence in complete disregard to the mitigating circumstances such as age, ailments and the sufferance of protracted trial for now almost 20 years each of the appellants."

According to the sessions judge, the order of the lower court on sentencing "absolutely sidelined the criminal jurisprudence on sentencing that envisages punishment in proportion to the crime committed and sentence with the avowed object of deterrence and reformation".

But while it is good to see the courts go into these questions, one has to ask to what extent this should lead to a reduction in sentence, when the punishment under Section 409 – of life imprisonment no less – was still on the table.

The delay in the trial's completion is a tricky one. This is often because of the problems with the criminal justice system, but in this case, was also delayed by the multiple rounds of cases before the courts regarding the main case, including three decisions of the Supreme Court, which only ended in 2017.

For the Ansals to claim this should lead to a reduction in sentence is a bit rich, especially since, and this is worth remembering, they were trying to subvert the course of justice.

When it comes to old age and ailments, depending on the offences in question, the courts have not shown leniency to undertrials, let alone convicts, solely on this basis, as we saw with the death of Father Stan Swamy while awaiting trial in the Bhima Koregaon case, or with Sajjan Kumar's case over his conviction for his role in the anti-Sikh pogrom in 1984.

While we certainly don't want to see elderly and infirm people kept in jail out of a sense of vindictiveness, there has been no proof of reformation of the Ansals – indeed, as Neelam Krishnamoorthy has pointed out, they even lied on affidavit about the Rs 30 crore they contributed towards a trauma centre, claiming it was compensation rather than a court-ordered fine.

What is the message sent out to all other rich and powerful people who try to get the evidence in cases against them destroyed or tampered with, when those caught red-handed after getting public servants to do their dirty work, walk away with a mere eight months in jail?

The other question that needs to be asked in this context relates to the extent of this as a mitigating factor. Ok, the person is old and has severe ailments, so their sentence needs to be reduced, but by how much?

If the original sentence which could be imposed was one or two or even three years, then reducing the sentence to eight months is understandable. Even when the Supreme Court decided to factor in Sushil Ansal's age and ailments when reducing his sentence in the main Uphaar fire tragedy case, it accepted the reduction of his sentence from two years to one year (and accepted nine months as sufficient).

Life imprisonment or a longer punishment was never on the table in that case, but it was in this case. By no stretch of the imagination or any case law on mitigating factors does it seem fair to mitigate a possible sentence of life imprisonment – already down to seven years because the trial court didn't have authority to order a greater sentence – down even further to eight months.

The order of the sessions judge is yet another demonstration of the need for sentencing guidelines in India, something which has been suggested by Law Commission reports since the 1970s and multiple judgments of the Supreme Court.

Most courts fail to take appropriate mitigating factors into account when deciding sentences, but as this case shows, in the rare cases that they do, there are no benchmarks that they have to follow, allowing a confusing degree of discretion.

A good set of sentencing guidelines would help ensure that the courts are not only reminded of relevant mitigating factors, but would also know to what extent these can reduce a sentence, to prevent the justice system from becoming a mockery, and allowing the rich and influential to game it.