More than two decades ago in 2003, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in Madhya Pradesh on the promise of sadak, bijli aur pani, routing the Digvijaya Singh-led Congress by projecting itself as a party of efficient governance. Good roads, uninterrupted electricity, and, crucially, safe drinking water were held out as guarantees of a new administrative culture.

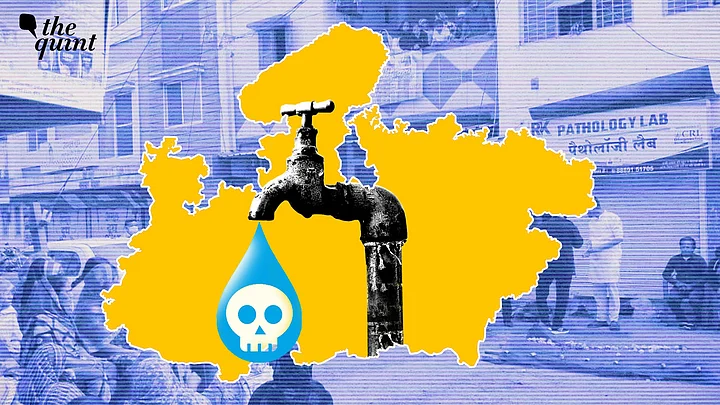

Twenty years later, all three promises still limp along—but it is water, the most basic public necessity, that has now turned deadly in Indore, the state’s most celebrated urban success story.

At least 15 people have reportedly died after consuming contaminated drinking water in Bhagirathpura, a densely populated, economically weaker locality of Indore—a city that has been branded India’s cleanest since 2017. However, the official figure of death is four.

Spurious Water in Indore

More than 200 residents have been hospitalised across 27 hospitals, with families spending frantic nights attending to the sick as fear ripples through the neighbourhood. The crisis began late night on Monday, 29 December, when residents started vomiting violently, followed by high fever and dehydration. By morning, the scale of the tragedy was impossible to deny.

Among the dead is six-month-old Abhyan Sahu. His mother, Sadhna Sahu, a private school teacher, simply confirms the loss: “I have lost my son.”

His father, Sunil Sahu, who works from home, is more direct. He tells The Quint: “It was the contaminated water that took his life.”

Bhagirathpura, home to around 15,000 people, has scarcely a household untouched by illness. This was not an isolated accident; it was gross negligence amounting to a criminal act.

The residents also said they had been raising the issue for long but in vain. During a visit to the affected Bhagirathpura area on 1 January, residents surrounded Kailash Vijayvargiya, local MLA and also minister for urban administration and development (UAD), telling him: "Kai dino se dooshit paani ki shikayat ki ja rahi hai lekin kisi ne sunvaai nahin ki" (For days, we complained about contaminated water, but no one listened). The minister faced protests as well as public anger.

Preliminary findings suggest that the water supply line was contaminated by sewage, allegedly due to leakage from a toilet constructed at a local police check post.

The implications are damning: failure of engineering safeguards, lack of routine inspection, and the absence of real-time water quality monitoring. These are not unknown risks. "They are textbook urban governance failures," a senior government official in the state secretariat told The Quint.

Not the First Complaint

The official response followed a predictable script. Under public pressure, a show cause notice was served to Dilip Yadav, Commissioner of Indore Municipal Corporation, and Additional Commissioner Rohit Sisonia was transferred. However, late in the night, the Commissioner was transferred, and Sisonia, along with incharge superintendent engineer Sanjeev Shrivastava, were suspended.

Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Mohan Yadav, who is also incharge of Indore district (every district in the state has an incharge minister to supervise the administration), announced administrative action. The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has sought a response from Chief Secretary Anurag Jain within two weeks.

But even as families grieve, the state has appeared eager to narrow culpability. Sanjay Dubey, Additional Chief Secretary, Urban Administration and Development, stated that while nine deaths have been reported, “based on post-mortem reports, at present only four can be attributed to contaminated water.”

This is not an isolated lapse in Indore, nor in Madhya Pradesh. Neither was this the last warning.

In late 2025, at least six children aged between three and 15 undergoing treatment for Thalassemia at government hospitals in Satna tested positive for HIV, allegedly due to contaminated blood transfusions. The blood bank incharge was suspended, but the episode laid bare chronic failures in donor screening, storage protocols, supervision, and independent audits—the invisible architecture of public health safety.

That same year, Madhya Pradesh witnessed another devastating scandal: the deaths of around 24 children after consuming contaminated Coldrif cough syrup. The syrup was found to contain diethylene glycol (DEG), a toxic industrial solvent known to cause acute kidney failure.

Once again, the victims were children whose families trusted government-supplied medicine. The response—suspension of a government paediatrician—reduced a multi-layered regulatory collapse to individual fault.

Taken together—poisoned water in Indore, rats in a neonatal ICU, HIV infections through blood transfusions, and toxic medicine killing children--these are not coincidences. They point to a systemic collapse of monitoring, supervision, and accountability. The state intervenes not to prevent harm, but to manage outrage after lives are lost.

Govt Missing Amid Political & Administrative Lapses

The ambitious Narmada water supply project in Indore is among the party’s most advertised achievements, prominently featured alongside flagship schemes like Ladli Behana Yojana. Kailash Vijayvargiya has represented the area for decades. If even Indore cannot guarantee safe drinking water, the claims of governance elsewhere ring hollow.

Former Chief Minister Uma Bharti broke ranks to call the incident a "mahapaap". She wrote on X, “It is not only the mayor. The government and administration are responsible. All those responsible, from top to bottom, should be punished. The value of life is not Rs 2 lakh.”

Her words cut through the ritual of compensation announcements that too often replace accountability.

Despite repeated claims of lifting Madhya Pradesh out of the so-called 'BIMARU' category, the state continues to fail on core human development indicators—foremost among them, safe potable water.

Under Article 21 of the Constitution, the right to life includes the right to health and safe living conditions. When the state supplies water, blood, medicine, or hospital care, it assumes constitutional responsibility for their safety. These deaths are not misfortune; they are governance failures.

The tragedy of Bhagirathpura was foreseeable, preventable, and therefore indefensible. Cleanliness rankings and promotional campaigns cannot mask corroded pipes, vacant posts, lax inspections, and a culture of denial.

Indore’s poisoned taps have stripped the sheen off official narratives. Until accountability travels upward—beyond suspensions and transfers—and systems are rebuilt with seriousness, sadak, bijli aur pani will remain political slogans, not constitutional guarantees.

(Deshdeep Saxena is an independent journalist reporting on news and politics from Madhya Pradesh.)