Amid Hindutva Threat, Dalit Christians May Have a New Champion in Cardinal Poola

As the first national Dalit face of Indian Christianity, Poola brings hope. But symbolism alone isn't enough.

advertisement

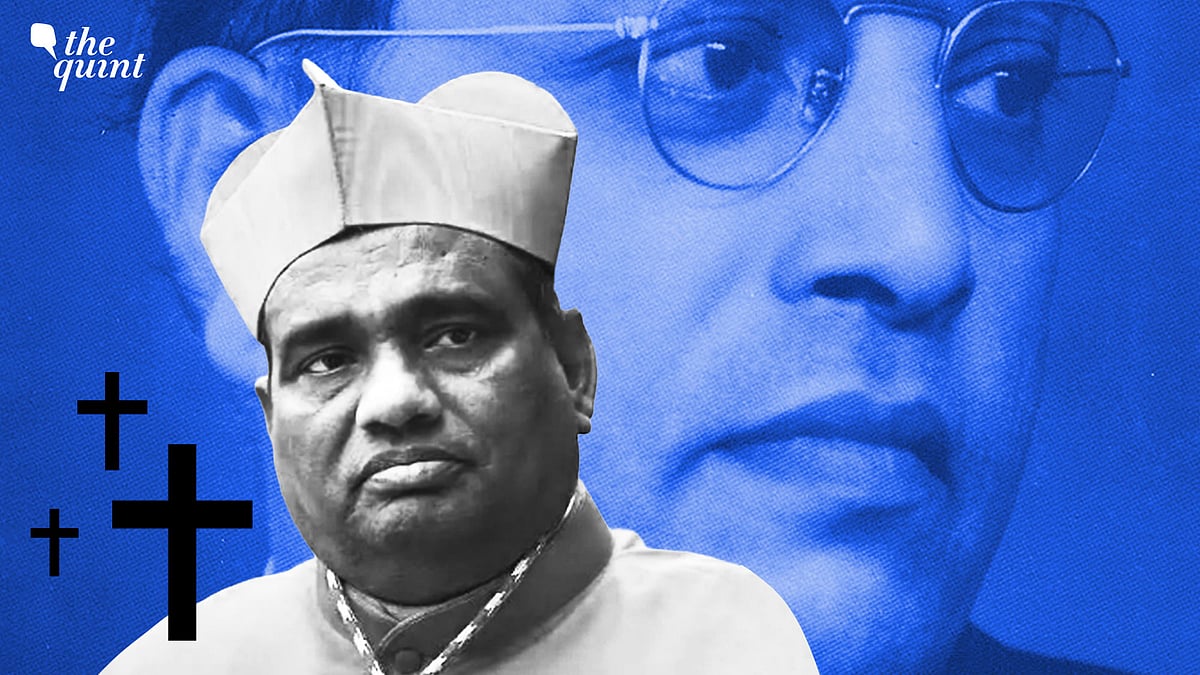

Anthony Poola, the Archbishop of Hyderabad, made waves in 2022 when he was elevated as a Cardinal by Pope Francis in the Vatican.

Now, on 7 February, he has been elected President of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India (CBCI), the first Dalit to become the national face of Indian Christianity, which in its 2,000 years in the land has imbibed its culture, and absorbed all the ills of its caste structure.

Caste has survived Gautama, Mahatma Phule, and Bhimrao Ambedkar. Poola’s ascendancy will not end caste in the Catholic Church, much less the nation, but it is far more than a symbolic gesture. It heralds transformative possibilities for the Catholic Church, as well as for Dalit Christians and other marginalised communities across India.

Caste in Indian Christianity

India’s Catholic population, estimated at around 20 million, comprises predominantly of the Latin Rite (approximately 70 percent) and the two “Oriental Rites”—the Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara Churches, both owing allegiance to the Pope in Rome, and centered chiefly in Kerala. In recent years, the Pope has permitted the two Oriental Rites to be present across india, essentially meaning that all three of these Catholic groups have equal rights and opportunities to establish institutions and churches anywhere in the republic.

Historically, Dalits, who constitute roughly 65 percent of Indian Catholics, and are almost entirely in the Latin Church, converted to Christianity seeking escape from the rigid caste system’s oppression.

Since its founding in 1944, the CBCI has functioned as the apex “supra-ritual” episcopal body uniting these three Rites. Yet, leadership has predominantly reflected upper-caste or non-Dalit clergy, mirroring broader societal inequalities.

The Catholic Church in India faces a dual legacy as both an agent of liberation and, at times, an enabler of caste discrimination. The CBCI’s 2016 Policy of Dalit Empowerment, though visionary, has encountered implementation challenges that must be addressed decisively.

In the Latin Catholic Church, which dominates northern and western India, Dalits form the majority in many dioceses but remain grossly underrepresented in leadership.

There has never been an internal caste census in the Catholic Church, or any other church, but it is estimated by those in the Dalit movement that out of roughly 180 bishops nationwide across all Rites, only about 12 are Dalit, a stark 6.7 percent. Tamil Nadu-Puducherry, with a 75 percent Dalit Catholic population, has just one Dalit bishop among 18.

Socio-Legal Invisibility of Dalit Christians

Poola’s presidency offers the church an opportunity to address these systemic inequities. In their many appeals to the Nuncio, the Pope’s ambassador and eyes in India, Dalit Christian leaders have called for mandatory Dalit appointments to episcopal vacancies. Poola’s leadership, therefore, aligns with the church’s Dalit empowerment policy, which recognises caste discrimination as a grave social sin.

His tenure could drive reforms enhancing pastoral outreach in Dalit-majority areas, especially where caste tensions have escalated to legal interventions, such as the 2025 Supreme Court case addressing discrimination in Tamil Nadu’s Kottapalayam parish.

In February 2025, the Supreme Court issued a notice regarding a Special Leave Petition filed by members of the Dalit Catholic Christian community from the Kottapalayam parish in the Kumbakonam Catholic Diocese of Tamil Nadu.

The Oriental Rites—the Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara Churches—present a different challenge. These churches have traditionally had a more homogeneous upper-caste leadership, and no Dalit bishops, despite some Dalit populations in their peripheries.

Experts say Poola’s position could foster inter-Rite dialogue, urging adoption of inclusive policies and broader access to education and healthcare institutions for Dalits. Although these Rites enjoy autonomy, their participation in the CBCI offers a platform for collaboration toward a more synodal and inclusive church, consistent with Pope Francis’s vision.

Moreover, there is a need to address intersectional discrimination faced by Dalit women religious leaders, who, despite comprising a significant portion of nuns, are often denied leadership roles. This holistic empowerment would represent a major step forward in dismantling caste and gender barriers within the church.

Poola’s election resonates beyond the Catholic fold, touching India’s entire Christian population of around 28 million, including Protestant and Orthodox communities.

The All India Catholic Union, a prominent lay Catholic body, has long denounced casteism and advocated for Dalit rights.

Such visibility strengthens inter-denominational solidarity, particularly as joint petitions and PILs before the Supreme Court seek Scheduled Caste (SC) status for Dalit Christians and Muslims.

These PILs, pending since 2004, argue that caste stigma persists despite religious conversion, a reality acknowledged by many but contested by the government, which maintains caste is exclusive to Hinduism. The court’s 2023 decision to proceed with adjudication emphasises the urgency of reform.

Surviving Hindutva and Anti-Christian Violence

Additionally, in a climate of rising anti-Christian violence linked to Hindutva nationalist rhetoric, Cardinal Poola’s election models inclusivity and minority representation, potentially easing communal tensions and reinforcing advocacy for religious freedom and minority rights.

Dalits face disproportionate hardships: they are overrepresented in prisons, underemployed, and experience higher poverty rates and lower literacy compared to national averages.

For instance, Dalits constitute 21.7 percent of convicts and 21 percent of undertrials despite being 16.6 percent of the population, indicating systemic bias in the justice system. Dalit women, facing multiple layers of oppression due to caste, gender, religion, and poverty, are especially vulnerable, as reflected by their high incarceration rates. Some among them are Dalit Christians, or “believers”, as they are more commonly known.

However, sceptics caution that symbolic leadership alone will not dismantle entrenched caste hierarchies without concrete policy action, enforcement of affirmative measures, and judicial outcomes favouring Dalit rights.

(John Dayal is a writer and activist. He is a former President of the All India Catholic Union. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)