If Aravalli Is Lost, Can North India Survive?

This isn't just a failure of administration, but a failure of a society that has forgotten how to understand nature.

advertisement

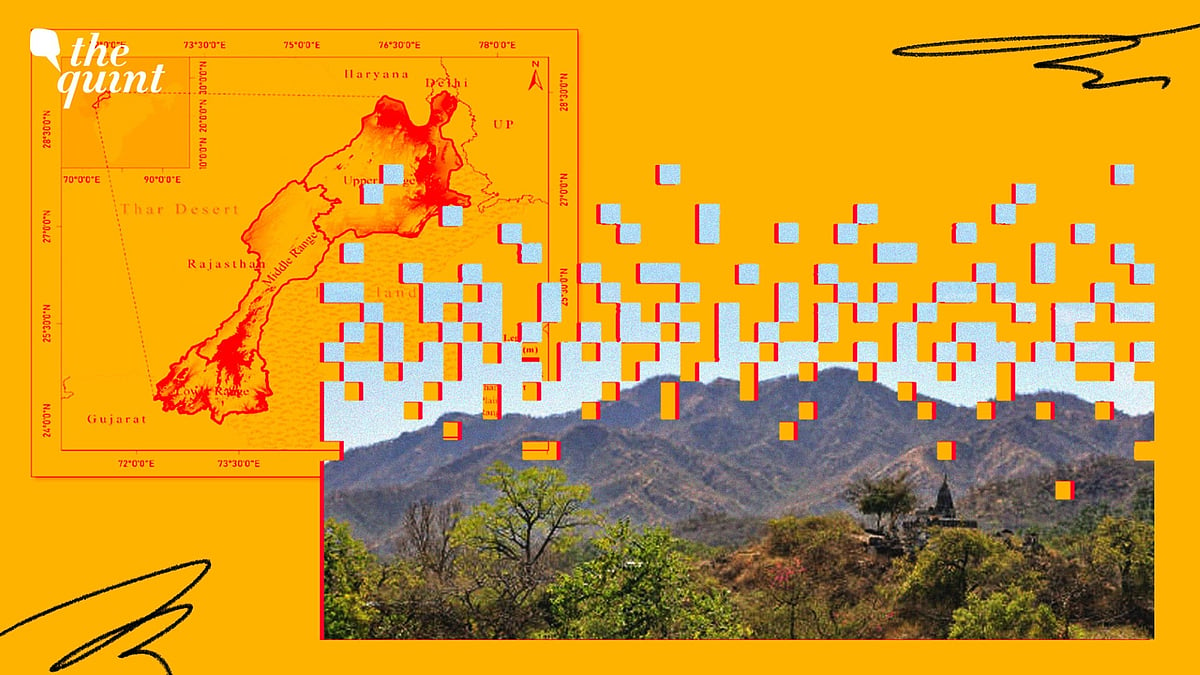

If you look closely at a map of India, a discontinuous, elongated mountain chain comes into view, stretching from western to northern India, fragmented in places, and nearly invisible in others.

It takes its first silent breath near the Delhi Ridge, moves southward across the rocky plateaus of southern Haryana, traverses the vast, sun-scorched landscapes of Rajasthan, and finally comes to rest quietly near Ahmedabad in Gujarat.

This mountain range is the Aravalli. Shaped by billions of years of tectonic upheaval, erosion, wind, rain, and time, it stands as one of Earth’s most ancient natural guardians. Its existence is so old that its rocks still carry the dust, ash, and memory of the planet’s formative epochs.

Like an elderly, contemplative sage; quiet, restrained, and enduring; the Aravalli has long stood watch over North India’s climate, groundwater, winds, and ecosystems.

Redefining Mountains by Measurement, Not Meaning

On 11 December (on World Mountain Day no less), as the Supreme Court ruled that only hill formations exceeding 100 meters in height would qualify for protection under regulations concerning the Aravalli range, that moment marked the beginning of a profound environmental tragedy.

As a climate scientist, it is evident that this failure is not merely administrative or technical.

It reflects a deeply flawed worldview one that attempts to reduce nature to land parcels and elevation thresholds, measuring ecological systems with a ruler rather than understanding them as living processes.

I have worked on mountain climate change across different regions, where mountains are often classified using thresholds of 500 meters or even 1 kilometer above sea level.

The lower slopes, foothills, and transition zones—often lying well below these arbitrary heights—are where vegetation regulates heat, where moisture is stored and recycled, where biodiversity concentrates, and where hydrological processes are most active.

Peaks may qualify as mountains on paper, but it is the lower and mid-elevation landscapes that enable mountains to function as climate systems.

A mountain range is, therefore, not defined by height alone. Yet, we continue to judge its value by numerical elevation, and in doing so, we reveal the starkest expression of our collective failure—mistaking measurement for understanding, and classification for wisdom.

The Aravalli is a Climate System, Not just a Landform

Mountain ranges, especially one as vast and spread out as the Aravallis, are the backbone of climate regulation, groundwater systems, ecosystems, and life itself.

The significance of the Aravalli cannot be measured in meters. When we imagine mountains, we think of peaks, slopes, mist, rain, and harsh weather. But the true importance of a mountain range lies not in its visible summits, but in its geological history, its capacity to regulate climate, and the hidden movement of water through its porous rocks.

The Aravalli is among the most critical stabilising forces of North India’s climate. Standing at the edge of the Thar Desert, this ancient mountain barrier slows, deflects, and weakens the hot, dry, dust-laden winds from the west. Its rocky ridges reduce wind speed, alter airflow, and prevent desert dust storms from sweeping directly into eastern Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi. Because of this natural barrier, the harsh desert climate does not fully engulf North India.

Climate scientists have repeatedly warned that if the Aravalli collapses, Delhi’s climate could shift toward semi-desert conditions within decades.

This is not an exaggeration. Large sections of the Aravalli foothills in Haryana and Rajasthan have already been flattened, quarried, and deforested.

The result is unmistakable: rising dust levels in Delhi, a 3-4°C increase in local temperatures, and increasingly erratic rainfall patterns. Numerous scientific studies now identify the degradation of the Aravalli as a major contributor to Delhi’s extreme air toxicity.

Though not as tall as the Himalaya, its slopes generate micro-scale atmospheric moisture; its vegetation retains humidity; and heat exchange between its rock surfaces and the atmosphere moderates daily temperature extremes.

Its intervention in the movement of monsoon winds is quiet yet decisive.

Temperature-pressure contrasts formed along its ridges bend wind trajectories, alter cloud movement, and help organise the monsoon flow toward the Himalaya.

The behaviour of the North Indian monsoon, its rhythm, variability, and spatial structure, depends on this invisible guidance. The Aravalli is the silent, stabilising thread in an extraordinarily complex climatic system.

The Aravalli, Delhi-NCR’s Hidden Water Source

Yet the most critical impact of the Aravalli lies beneath the surface, in its groundwater system.

From the outside, the range appears dry and austere. Inside, however, it sustains a slow, persistent flow of water.

Natural fractures within its rocks—fractured rock aquifers, form the foundational structure of regional water balance.

Rainwater does not simply run off the surface; it disappears into these fractures, percolates downward, and gradually becomes groundwater that sustains cities.

And how do we respond? We blast the rocks through mining, flatten the foothills for real estate profit, and strip away forest cover.

With each blow, the Aravalli’s capacity to store water diminishes. Once fractured aquifers are destroyed, they do not regenerate.

Their loss marks the collapse of groundwater itself. Borewells dry up, lakes shrink, and the seeds of future water scarcity are sown today.

The Aravalli is not only a climate regulator or a water reservoir; it is an exceptional biodiversity corridor.

Located at the ecological boundary between desert and forest, it supports a remarkable array of species: leopards, foxes, hares, peafowl, vultures, medicinal plants, and hundreds of grass species.

Each component of this ecosystem is interdependent. When hills are flattened, the entire ecological chain is disrupted. What was once a living, resilient landscape is reduced to a barren, lifeless expanse.

The Most Alarming Aspect of This Crisis is Human Perception

We have forgotten how to see mountains as mountains. To us, they have become mere land parcels or sites for construction, excavation, or “development.”

This mindset reflects not only ignorance of the Aravalli, but also a deeper ignorance of ecological systems as a whole.

When they collapse, humanity pays the price—through droughts and floods, rising temperatures, toxic dust, respiratory illness, heatwaves, and, most ominously, a growing tide of climate refugees.

The cities of North India that are now struggling under extreme heat are not facing isolated problems; they are living in the shadow of the Aravalli’s decline.

Rising temperatures in Delhi, persistently hazardous air quality, and escalating dust concentrations are all directly linked to the degradation of the Aravalli.

In the Gurugram-Faridabad region, the leveling of its slopes has disrupted natural airflow, dismantled heat barriers, and turned Delhi into a massive urban heat island.

Delhi, already the world’s most polluted capital, could become a dust-choked, semi-arid city, with groundwater levels dropping to 500 feet, rendering tap water a relic of the past.

International research shows that the human body cannot survive wet-bulb temperatures exceeding 50°C; beyond this threshold, the body’s thermoregulatory system fails. North India is now approaching this catastrophic boundary, and the destruction of the Aravalli is the single greatest force pushing it closer.

What Is Unfolding in the Aravalli Is Not an Isolated Regional Anomaly

This crisis is no longer anecdotal; it aligns precisely with how global climate science understands the vulnerability of mountain systems, and is firmly embedded in global climate science.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has repeatedly emphasised that mountain systems are among the most climate-sensitive regions on Earth, functioning as critical regulators of regional climate, water availability, and ecosystem stability.

Though not a high-elevation range, the Aravalli fits this framework: a low-elevation mountain system whose degradation intensifies heat extremes, accelerates groundwater loss, destabilizes monsoon patterns, and weakens natural climate buffers for millions downstream.

The IPCC warns that when such systems are fragmented by land-use change, mining, or urban expansion, their climate-regulating capacity collapses rapidly, with recovery taking centuries if at all.

The ongoing destruction of the Aravalli is therefore not merely a regional issue—it contravenes fundamental scientific understanding of climate adaptation.

The Picture Is Grim, but It Is Not Irreversible

Change is possible, but only if we transform how we perceive mountains. Mountains are not obstacles to development; they are the foundation of sustainable development.

Viewing an ancient structure like the Aravalli through the lens of real estate is an act of profound ignorance.

Its protection must be placed at the center of decision-making by governments, industries, political systems, and citizens alike, because when the Aravalli survives, the region survives. When the region survives, civilisation endures.

We stand today at a decisive crossroads. Science, society, policymakers, and citizens must respond together.

The Aravalli is not just another landscape; it is the lifeblood of North India. Protecting it is an act of self-preservation. Every blow struck against it is a wound inflicted on our future. Every step taken to protect it is a path of light for generations to come.

This ancient, silent mountain guardian still stands solemn, patient, and bearing witness to billions of years of Earth’s history.

The question is simple, and urgent: Will we finally learn to understand it, or will we destroy it and carve the path to our own collapse?

(Dr Pratik Kad is a Climate Scientist, currently working as a PostDoc at NORCE Research in Bergen, Norway. He is an affiliated member of the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research.This is an opinion piece and views expressed are the author's own. The Quint does not endorse nor is responsible for them.)