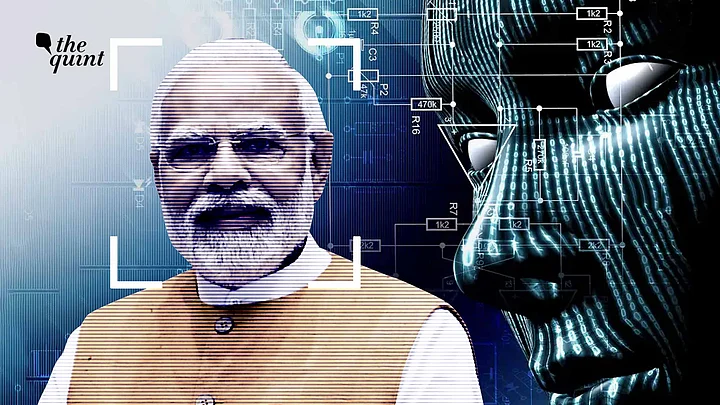

Deepfakes of celebrities and high-profile figures have set off panic bells in India, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently raising the alarm over the threats posed by the rapidly evolving technology.

If there were any doubt, the proliferation of AI-generated deepfakes is a real issue with the potential to inflict serious harm. Then it's probably a good thing that the prime minister has recognised it as a "new" and "emerging" crisis.

So, how do we fix it? In a meeting with representatives of OpenAI (the company behind generative AI tools ChatGPT and DALL-E), PM Modi said that he had suggested adding labels to deepfakes, similar to anti-tobacco warnings.

But that's not really how it works, fact-checkers pointed out to The Quint.

Catch Up: Centre Gets Cracking (Down) on Deepfakes

Amid the mounting concerns over deepfakes, the Centre is contemplating new legislation. "We will start drafting the regulations today itself and within a very short timeframe, we will have a separate regulation for deepfakes," Union Minister of Electronics and Information Technology Ashwini Vaishnaw said in a press conference on 23 November.

In particular, Vaishnaw revealed that the regulation would levy penalties on users who create or upload deepfakes. Provisions to help users tell deepfakes apart from original content are also likely to be part of the new legislation. A "clear and actionable plan" is also being drafted, focusing on:

Detection (of deepfakes)

How to prevent the spread of misinformation

How to strengthen reporting mechanisms (such as in-app reporting mechanisms)

Increasing awareness

The Centre's decision to frame new legislation came after a meeting with representatives from Meta, Google, YouTube, X (formerly Twitter), Microsoft, Amazon Web Services, Snap, Sharechat, Koo, Telegram, and industry body NASSCOM.

IIT Jodhpur computer science professor Mayank Vatsa and IIT Ropar data science professor Abhinav Dhall also attended the meeting, according to Hindustan Times.

Another meeting with social media platforms is reportedly on the cards in the first week of December.

Expand

'Not Foolproof', 'Can Be Cropped Out': Fact-Checkers on Deepfake Labels

"Labels can be cropped out of a photo or trimmed from a video," Karen Rebelo, the deputy editor at BOOM Live, a fact-checking organisation that's based in Mumbai, told The Quint.

However, it also depends on how the labels are incorporated.

"As far as labels that are invisible to the human eye but can be detected by other software go, most social media platforms and messaging apps strip out metadata," Rebelo said.

Metadata comes embedded in the image or video file and generally comprises identifiers such as creation date, location, persons or products shown, and other details, according to The International Press Telecommunications Council (IPTC).

Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Slack have been known to partially scrub metadata from uploaded content. "So unless these companies create a label that can somehow bypass that process, I don't know how helpful labels will be," Rebelo added.

"Labelling AI images, which is often called ‘watermarking’, has the potential to help people know what online content is real and what is not. But it is not foolproof," said Ilma Hasan, a senior editor at Logically Facts – the independent fact-checking unit of AI tech company Logically.

"Even if images are watermarked, those markers can be removed. You can already find software on the dark web that does this," Hasan said.

On a side note, labelling content made by AI is also something that Adobe, Microsoft, Google, and others are pushing for through the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA). But, as Hasan pointed out, open-source AI tools that aren’t built by the big AI companies would sit outside such initiatives. "They can’t be forced to use them," she said.

Hence, efforts to develop labelling or watermarking should continue but they cannot be the mainstays of any strategy or framework to tackle deepfakes, Hasan added.

If Not Deepfake Labels, Then What?

"An effective strategy should give greater emphasis to identifying the types of coordination and tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) that disinformation actors (and the AI models they train) use to actually get that content in front of audiences via social media networks," Logically Facts' Ilma Hasan said.

She also appeared to be on the same page as PM Modi on the role of the media in tackling deepfakes.

"There is real potential for tailored media literacy programmes that trigger interventions when online behaviours associated with disinformation are identified. This would help in situations where no label has been applied, or it has been removed," Hasan opined.

“We should educate people, through our programmes, about what a deepfake is, how big a crisis it can cause, and what its impact can be,” Modi had said in his 17 November speech at the BJP headquarters in New Delhi.

The media has a legacy of being taken seriously and they should take on the responsibility of creating awareness, the prime minister had further urged.

Deepfakes Are Getting Easier To Create, Harder To Catch

Even as a viral deepfake of actor Rashmika Mandanna snowballed into a major regulatory concern in India, people in the United Kingdom were getting their own taste of AI-generated deception.

In deepfaked audio clips posted online, London Mayor Sadiq Khan was heard calling for the First World War Remembrance Day to be postponed as it clashed with a pro-Palestinian march that had been organised on the same day.

"Although the wording of the clips is too extreme to be plausible, both do reflect the intonation of the London mayor’s voice, demonstrating the level of online fakery that can be achieved," The Guardian reported.

"With generative AI tools becoming increasingly sophisticated, we can anticipate the quality of the content they produce improving, and audio and video of influential people such as political leaders being used to spread disinformation or push certain narratives – potentially triggering strong reactions," Hasan said.

While it's becoming easier to create a deepfake, what's more troubling is that it's also becoming harder for fact-checkers to debunk them. "In the last 12 months, this [deepfake] technology has rapidly outpaced any sort of detection tools or methods that are out there," Boom's Karen Rebelo said.

"Currently, we have a system where we are using a lot of other ways to tell that something didn't happen or something is not true. For instance, we try to reach out to the source, or we say that this is not logically possible," she explained.

But in terms of the [deepfake detection] tools that are out there, they are not very reliable as they give a lot of false positives, Rebelo opined.

Additionally, out of the various types of synthetic media, Rebelo singled out AI voice clones as being "nearly undetectable" since they don't sound mechanical or robotic.

"And the danger is not only in the field of misinformation as [AI voice clones] can also be used to defraud people and scam them into losing their hard-earned money. So it opens up a whole can of worms," she added.

The Problem With Equating Deepfakes to Misinformation

While speaking about deepfakes, PM Modi remarked on how he'd come across a manipulated video of him playing garba. “I recently saw a video in which I was playing garba... it was very well done, but I have never done garba since school,” he said.

However, the video that Modi likely believed to be a deepfake turned out to be an authentic clip featuring Vikas Mahante, the prime minister's doppelganger.

The confusion around Modi's garba video raises another important question: As deepfakes become synonymous with misinformation, what are the chances of real videos being labelled and dismissed as fake?

That possibility actually has a name – liar's dividend, a phrase coined by two law professors for when deepfakes undermine people's trust in all content regardless of their authenticity.

And the liar's dividend of deepfakes can be leveraged by politicians to dismiss anything that's true but inconvenient for them, according to fact-checkers.

"What will happen is that as this deepfake technology gets better and better, your politicians can always come around and call everything a deepfake, and say it's not true," Rebelo said.

She further pointed out that it could happen to a news organisation that publishes a sting report where there's an audio recording or video of a politician caught doing something.

Something of the sort has already happened in India, when in July 2023, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) leader Palanivel Thiagarajan claimed that damning audio clips of him accusing his own party of corruption were fabricated using AI.

There's also a degree of ambiguity on what is and isn't a deepfake. "When we are talking about deepfakes, we are specifically referring to any synthetic videos, images or audio that has been created using deep learning algorithms," Rebelo said.

"But that's another issue. Everyone is calling anything and everything a deepfake. There's still old-school Photoshop and lots of ways to manipulate content," she added.

When asked if we need a better definition of deepfake, Rebelo said that the terminology was bound to evolve. "There are misinformation researchers who are looking at what's playing out right now, not just in India but everywhere in the world," she further said.

Another aspect caught in the tide against deepfakes in India is the ethical usage of such technology. "Deepfakes might not necessarily always be used to spread misinformation, it may be used to reach wider audiences, to create art or for entertainment purposes," Ilma Hasan said.

For instance, deepfake dubbing can be used to help translate movies and TV shows into other languages without making it seem like the actor's lip movements are off.

The healthcare industry has also seen positive use cases of audio deepfakes, with doctors and researchers using it to help patients regain their natural-sounding voice.

However, it remains to be seen whether or not the government's regulatory response to deepfakes considers their potential to be used for good.