“Many opinions, just as many paths”

- Ramakrishna

“And the haters gonna hate, hate, hate, hate, hate”

- Taylor Swift

The Aditya Dhar-directed Dhurandhar's four-minute trailer, promising a cross between an Indian spy film and a Pakistani gangster drama, begins with an incendiary scene of a Pakistani army major brutally torturing a man—while adding that this is what he wishes to do to India, bleed it by a thousand cuts. Expectedly, the trailer has drawn both praise and ire.

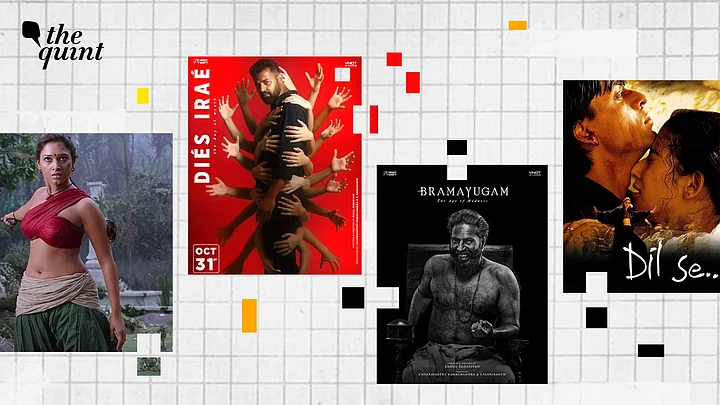

Caught in the middle, however, are aesthetes, having to reconcile a film's low-grade politics with high-end craft. Earlier in November, the re-release of Mani Ratnam’s Dil Se.. reignited chatter over how Amar (Shah Rukh Khan) is a stalker and sex pest. Many on X wondered if such a film would be made today–not just because of Amar’s creepy insanity but also since the film is critical of the Indian nation state.

Malayali horror maverick Rahul Sadasivan’s latest Diés Iraé was also in theatres at the time. The film follows a wealthy playboy haunted by the ghost of presumably an ex he ghosted. Sadasivan’s previous, the acclaimed Bramayugam, was also a Gothic tale but dominantly spun around Hindu mythology.

Horror, Hindutva, Propaganda: Decoding 'Visual Philosophies'

Kerala journalist Nidheesh MK argued in an Instagram post: “Rahul Sadasivan is the best thing [sic] happened to Hindu right in Kerala in recent times… His work re-enchants Hindu ritual (with all its castelst markings) in a way that feels aesthetically elevated. The Hindu right has to encounter faith cheapened in Kerala, through sloganeering, Rahul makes belief look Intelligent, stylish, cinematic. His films restore dignity to superstition and ritual, turning them from ‘backward’ relics into visual philosophy.”

Adding that critics praise Sadasivan’s craft without “addressing the ideology”, he wondered if Sadasivan is also right-wing.

A similar fuss over a filmmaker’s politics appeared in a review of the recent release De De Pyaar De 2. The film is an age-gap romcom written by Luv Ranjan (Pyaar Ka Punchnama), an expert in juicing potboilers out of cis-het gender politics. Film critic Rahul Desai made an interesting declaration: “We live in an age of relentless commentary; storytelling is only a vessel.”

While I am unbothered about these films’ politics (I have other issues with Dil Se.., I don’t think Sadasivan is a crypto-Sanghi, and it scares me to have to think so much about the maker of Sonu Ki Titu Ki Sweety), I did have trouble digesting some other recent critical darlings.

The Leonardo DiCaprio-starrer One Battle After Another got raves for addressing liberal panic over White supremacy and the crackdown on immigrants in the US. Aranya Sahay’s indie Humans in the Loop, released in September, argues how Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not unlike a child’s brain; the right input from the right people can make AI right.

Christopher Nolan’s last film Oppenheimer was centered on the eponymous atom bomb inventor’s guilt over two lakh deaths in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In one scene, then US President Harry S Truman asks Oppenheimer to get over himself: “You think anyone in Hiroshima or Nagasaki gives a shit who built the bomb? They care who dropped it. I did. Hiroshima isn't about you.”

I absolutely couldn’t swallow the silly, biteless treatment of Leftist rebels and Right-wing fascists in OBAA. Humans in the Loop felt like a picture-postcard apologia for AI. Oppenheimer was typically Nolan: bombastic and just about smart enough to not worry the financiers.

So, I get worked up over the politics of one set of films but not another. I get carried away by Sadasivan’s aesthetics, but I could not be swayed by the genius Paul Thomas Anderson’s in OBAA. Is there a right (or better) way of looking at a film? And which one is it: politics or aesthetics?

Schools of Film Criticism: Craft vs Purpose vs Meaning

Rewind to the 1950s when post-World War II film critics passionately argued in favour of recognising cinema as an art form, not just an industrial product. Chief among these were Manny Farber and Andrew Sarris, most famous for importing auteur theory from France. If you see a writer calling Sandeep Reddy Vanga an auteur, you can trace the blame to Sarris.

These critics focused on the idiosyncrasies of a filmmaker’s personal style (similarities in shot-taking and cutting) or hangups (similarity in themes explored) as observed over a lengthy period. This is how the French pushed the US critics to take Alfred Hitchcock seriously as an artist, not just a hit director of pulp fiction.

As the Vietnam war, the 1968 riots in Paris, and second-wave feminism got White American men hot under the collar, film criticism got a booster shot from these political currents.

Laura Mulvey’s dynamic 1973 essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema introduced the idea of “male gaze”. Mulvey, drawing from Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan, argued that men, in order to not feel “castration anxiety”, fetishise women or assume the role of their saviour. This tacit understanding within a patriarchal symbolic order where the makers and the audience are in collusion over controlling feminine agency is what Mulvey pointed out–the basis for Indian critic Anna MM Vetticad’s film reviews.

Vetticad, who calls herself “the world’s most committed feminist” on Instagram, argued in a viral 2015 piece how the hero’s (Prabhas) non-consensual physical flirting with the heroine (Tamannaah Bhatia) in Baahubali Part 1 was tantamount to rape.

In that piece, Vetticad had written:

“This aggressive display of ‘love’, in particular, is set against a gorgeous landscape with gentle music playing in the background. The beauty of the scene is designed to lull us into an acceptance of its insidious imagery and message, an acceptance that is bound to attract at least some reactions such as ‘stop nitpicking’, ‘have you lost your sense of romance?’ and the standard ‘chill, relax, it’s just a film’ to this column.”

Prescient of her. The piece got a second life recently when Bhatia criticised it on a YouTube channel and Vetticad hit back.

bell hooks, in a 1992 essay, introduced the idea of the “oppositional gaze”. Noting how Black women are invisibilised in American film, and even in critiques by White feminists, hooks pointed out the power in looking back into the eyes of your oppressor. hooks’ “oppositional gaze”, together with the Pandora’s box that was Mulvey’s essay, divided film criticism into two halves: the formalists and the political critics.

Filmmaker-critic Rajesh Rajamani’s entertainingly argued takedown of Mani Ratnam’s soft Hindutva in a 2020 essay has its roots in hooks' work. Like Nidheesh MK’s post about Sadasivan, Rajamani’s essay also had the attitude of catching a kid who had been naughty all along, hiding his dirty thoughts behind pretty images.

Fighting the political critics was lone wolf Pauline Kael, arguably the most influential American film critic of all time. Kael was a fan of the vulgar pleasures of film. In her 1969 essay Trash, Art and the Movies, Kael wrote, “Movies—a tawdry corrupt art for a tawdry corrupt world—fit the way we feel. The world doesn’t work the way the schoolbooks said it did and we are different from what our parents and teachers expected us to be. Movies are our cheap and easy expression, the sullen art of displaced persons.”

Nineties’ brat pack Anupama Chopra, Baradwaj Rangan, Raja Sen, and Jai Arjun Singh come from the Kael school of criticism. Unlike Rajamani, who critiques from an Ambedkarite lens, or Vetticad, these critics primarily zero in on the film’s aesthetic value and formal rigour.

These four also popped up in the late 1990s-2000s, when the political turn in film criticism got a bullet in the head from film theorist couple David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson. Neo-formalists Bordwell and Thompson questioned the point of plucking scenes from films, not unike Dil Se.. or Baahubali, and making cinema accountable for the world’s miseries. They believed film scholars should be solely concerned with craft.

In a post-9/11, Web 2.0 world, as voices from the global south invigorated film criticism, the cis-het White hegemony in the field got shaky.

The next batch of Indian film critics, which includes Desai and Rajamani, alongside contemporaneous Western critics like Angelica Jade Bastién, tilt heavily towards political criticism.

Which explains Desai’s line about living in an age of “relentless commentary” and storytelling being a “vessel”; in this point of view, films exist as a Blue Dart for politics.

Multiplicity of Voices a Must but it's a Two-Way Street

Rangan, who inspired a generation of Indian film reviewers, was visibly shocked by the online responses to his review of firebrand Dalit filmmaker Pa Ranjith’s Madras. Back in 2013, Ranjith’s politics was yet to aggressively appear in the forefront. Rangan read the film as a generic drama about angry youth and bad politicians, saying it was “beautifully made with little to say.”

The commenters on his website took him to task, pointing out the film’s Ambedkarite philosophy. Rangan’s responses suggest he was encountering a new language for the first time.

Where do I stand? I feel it was correct Rangan got schooled on Ambedkarite politics. Vetticard was correct. Rajamani’s essay is well argued, though calling Ratnam’s politics “hypernationalist” looks funny in 2025 with multiple Ramayana-inspired behemoths in production alongside garden-variety trash from Vivek Agnihotri.

Similarly, as an individual tilted towards Leftist politics (I find it strange to argue from an interdisciplinary lens–what the hell do I know about being a woman or a Dalit? But I know what it is to be poor), I was not on board with One Battle After Another, Oppenheimer and Humans in the Loop.

Leftist militancy and the Right-wing ghouls today deserve serious treatment–I recommend the 2022 film How To Blow Up a Pipeline. Fetishising a White man’s guilt for three hours against the tragedy of the country he was responsible for bombing is a personality I don’t understand. And that you can tame a capitalist virus with woke input from benign Brown women in rural India is an idea I find insidious.

At the same time, Nidheesh MK’s concerns over Sadasivan appear crazy to me. Aesthetically elevating religious rituals is a prerequisite for both the literary Gothic tale and the modern horror film which emerged in the West. Unless the characters in his films are taking religion and the supernatural seriously, the audience won’t.

In her 1963 essay Against Interpretation, Susan Sontag wrote, “Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art. Even more. It is the revenge of the intellect upon the world. To interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world–in order to set up a shadow world of 'meanings.’”

Since that essay, the real world and the shadow world have become indistinguishable. Nothing is what it seems, and every meaning is up for grabs. In this nihilist time, then, the best we can hope for is finding joy in a multiplicity of voices, warts and all. Surely, there’s space for all, “The open-hearted many, the broken-hearted few.”

(The author is an independent film, music, and culture journalist from Kolkata. This is an opinion piece. The views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)