The ruckus that killed the traditional debate on the motion of thanks to the President is another blow for the already endangered institution of Parliament in India. So fierce was the battle to settle scores past and present that both the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress-led Opposition seemed to forget that they were actually striking at the very foundation of the forum that gives them legitimacy as representatives of the people.

The casualty was freedom of speech, with neither the Leader of Opposition (LoP) Rahul Gandhi nor Prime Minister Narendra Modi being allowed to speak in what is the first major debate of the crucial Budget session.

The guarantee that forms the bedrock of our democracy is enshrined in Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. It seems to be in danger of vanishing not only from civil society interactions but even from the hallowed chambers of Parliament.

Knives Out

After such a stormy start with both sides using scorched earth tactics against each other, it is difficult to imagine how the budget session will proceed from here. This is the longest of the three sessions held annually. It requires tact, patience and commitment from both sides to keep it going in a meaningful manner for two months.

But with battle lines drawn so sharply and communications channels blocked by vitriol and hostility, it seems near impossible for the ruling BJP and the Opposition to step back and hammer out a compromise that will restore order, ensure that the session runs without ugly disruptions and save Parliament from further degradation.

There are many important issues on the table for discussion. First and foremost is the budget itself. Given the polarised mood of the political class, is there any scope for a meaningful debate on the government’s fiscal policies for the coming financial year?

Or will this also fall victim to power play between the treasury benches and the Opposition and be passed by voice vote amid pandemonium like the motion of thanks?

Additionally, apart from pending legislative business, there are hot potato concerns that need clarity like the Indo-US trade deal, which is obscured by differences in statements coming from Washington and New Delhi, the revelations in the Epstein Files which mention names of a leading industrialist and a senior minister in the Modi government, the controversy that has arisen over retired army chief General MM Naravane’s yet to be published memoirs that give a detailed account of what transpired within the government as India and China came face-to-face again in the Ladakh area within weeks of the Galwan clash and the potential impact on national security from development across the border in Bangladesh.

Public Concerns on the Backburner

And then there are issues that worry the public at large like the pollution crisis across the country which is taking a toll of people’s health and livelihoods, possible environmental damage from the government’s plans for mining in the Aravalli Hills which provide a vital green cover for Delhi and parts of Haryana, growing economic distress in the agriculture sector and the continuing tensions in strife-torn Manipur among others.

Parliament is the Constitutionally sanctified platform where questions are asked and answers are given. But if neither government leaders nor Opposition leaders are allowed to speak, then vital issues get buried or relegated to the realm of speculation and mistrust.

It is unfortunate that both sides flashed knives from the very first day that the two Houses met after the President’s annual address to a joint sitting of Parliament. On one side was BJP firebrand MP Tejasvi Surya who called the Congress anti-national while opening the debate for the treasury benches.

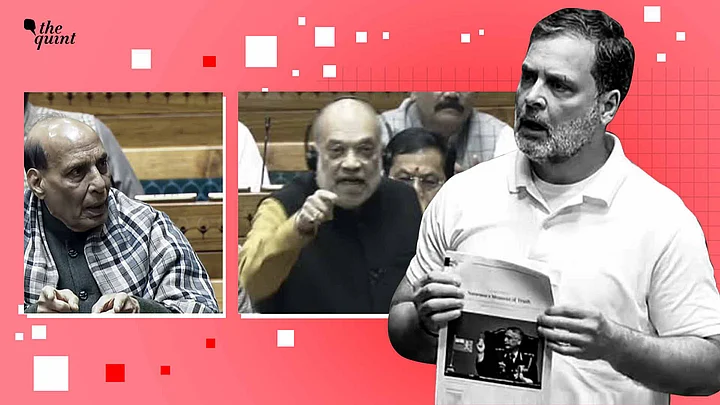

Rahul Gandhi hit back by flagging national security concerns arising from the 2020 India-China face-off in Ladakh. As is well known, he was not allowed to speak because he wanted to quote from Naravane’s unpublished memoirs, excerpts of which have been carried by a leading magazine.

Opposition Must Fess Up Too

Enough has been written about the role of union ministers Amit Shah and Rajnath Singh as well as Speaker Om Birla in silencing Gandhi. If their conduct was unfortunate, the Opposition’s was no better. Led by the Congress, all opposition parties united to block proceedings for several days, culminating in unprecedented scenes on the day Prime Minister Narendra Modi was scheduled to give his reply to a debate that never happened.

Women MPs closed in on his seat, the PM ducked and the motion of thanks was adopted without debate, without the Leader of Opposition’s speech, without the PM’s reply and presence.

This is not the first time that a PM has not been allowed to exercise his constitutional privilege of replying to the motion of thanks. In 2004, then PM Manmohan Singh too was forced to forgo his right.

Then and Now

However, there is a difference between the two episodes which raises questions about the future of Parliament. In 2004, the opposition BJP not only blocked Manmohan Singh from introducing his ministers on the first day, it refused to allow him to speak on the motion of thanks.

Even as pandemonium prevailed, back channels were at work to find a way out. Ultimately, the Congress agreed that Manmohan Singh would not give his reply and the motion of thanks would be put to vote.

Unlike Modi, who ducked on the final day, Manmohan Singh came to the House, announced that both sides had agreed to proceed with the vote without his reply. Behind the tension, there was an amicable resolution largely because the Congress-led UPA government backed off from confrontation in the larger interest of paving the way for Parliament to function.

Although there was uproar in the Rajya Sabha as well, Modi was allowed to give his reply to the debate. However, judging by the aggressive tone and tenor of his speech, largely devoted to attacking the Congress and other opposition parties, there seems little scope for the kind of compromises the UPA made during its time.

For the past 12 years, the BJP has spent much of it time trying to delegitimise the Congress and the its first family, starting with Jawaharlal Nehru.

Now that the Congress has numbers in the Lok Sabha to give it a voice, it seems hell bent on paying the BJP back in the same coin in a bid to tarnish Modi’s image and denigrate the BJP as a usurper.

Ultimately, it is the government’s responsibility to run Parliament. But if neither the government, nor the Opposition seem interested in making the institution robust by following time honoured traditions, then the question arises: whither Parliament?

(Arati R Jerath is a Delhi-based senior journalist. She tweets @AratiJ. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)