From estimates of Maha Kumbh pilgrims to the alleged loss through 2G spectrum allocation, India's relationship with numbers is a blend of myth, politics, and hype. We are condemned to live with estimates which often stretch between the improbable and the impossible. Our enumerations reveal more about us than the phenomena they enumerate.

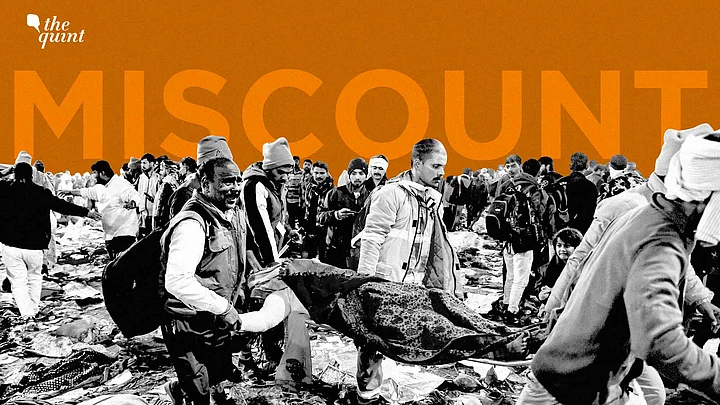

India’s perennial struggle with accurate counting is once again on display at the Maha Kumbh 2025. On the day of Mauni Amavasya, reports of attendance ranged from 5.7 crore to 10 crore. The special occasion, according to The Hindu, drew “more than 7.64 crore people”. The Indian Express editorial stated that “more than 10 crore people took the ritual bath Wednesday”. For NDTV, “more than 5.71 crore devotees took a holy dip in the Triveni waters” on the day.

The official estimate of total pilgrims throughout the mela – 40-45 crore – defies statistical plausibility. The sources for these estimates are never clear: some produce the numbers out of thin air, while other platforms, like CNN, quote, “local media reports”.

Such a huge participation would mean around one in every three Hindus in the entire world will attend this year’s Kumbh – that’s not even discounting the sick, elderly, toddlers, and the huge number of people misconstrued as Hindus.

The Number Game

Samajwadi Party leader Akhilesh Yadav has alleged that the actual number of people who died in the stampede is being hidden from the public. We do not yet know if this is true, but one can imagine that the state and Central government are keen to do so. Indeed, Reuters reports 39 dead, quoting police sources, while the official toll remains 30.

As Yadav pointed out, even the search for missing persons remains incomplete.

It took hours for even the initial reports of the dead to come out, even though many were brought dead to the hospital. The hesitancy in counting here is in stark opposition to the eagerness to overcount elsewhere.

But this habit extends beyond religious gatherings. Mass deaths are usually underreported, turnouts in election rallies are routinely exaggerated or left unclear, and census or survey data is often suspect.

Take the case of the number of people subjected to capital punishment since Indian independence. We have not had definite numbers.

The count varies from hundreds to thousands depending on who is counting. In 2005, the People's Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR) found a Law Commission report to prove that 1,422 executions took place betweem 1953 and 1964 against the then governmental figure of 55.

These are not merely instances of governmental lapse. We are strangely predisposed towards miscounting, and our relationship with numbers has long been peculiarly strained in the domains of history, demography, and governance.

This tendency transcends political differences and historical eras, as if we are haunted by a fundamental epistemic delusion.

On the one hand, we are helplessly drawn by the allure of large numbers. In our collective imagination, we are a behemoth made of crores and crores of people. We are always defined as a great collectivity; as individuals, we don’t count. On the other hand, we don’t hesitate to play down numbers as and when needed.

A Tradition of Miscounting

Miscounting is neither a modern nor a religious affliction in India.

From ancient epics to contemporary political rallies, numbers often serve an emotive rather than empirical function. The Kumbh Mela, for instance, has always been a spectacle of astronomical and unbelievable figures. Its attendance is justified by people on the ground who cite their witnessing of the humongous crowds.

It is well known, however, that the human mind fails miserably at estimating magnitude. We only excel at small counts intuitively. Above two digits, we quickly become unreliable and underequipped in quick counting; here, we must trust formal mathematics and science alone.

India’s contradictory and unscientific relationship with numbers manifests in everyday life.

Families report different incomes depending on the listener – richer for marriage alliances, poorer in front of tax authorities. Historical events, too, have undergone numerical inflation; the number of deaths in Jallianwala Bagh, the Punnapra-Vayalar uprising, and post-Independence riots are often contested.

Even the numerical scale of India's freedom struggle is periodically rewritten — how many martyrs, how many participants, how many sacrifices?

And what of the stupendously funny claim by Utsa Patnaik, Vijay Prashad, and Shashi Tharoor that the British stole $45 trillion from India? There is no answer to what has been happening to this produce before the British or after the British.

The 2G spectrum case had a similarly fantastic and baseless number: $25 billion or Rs 1.76 lakh crore.

Unlike crude propaganda, India’s habitual miscounting is organic, embedded in cultural and psychological dispositions.

Numbers in India acquire a ritualistic dimension, detached from their original purpose of quantification. This is not just political deception; it is a way of making meaning, a way of storytelling that turns statistics into myth.

During the migrant crisis triggered by COVID-19 lockdowns, the numbers of displaced workers were variously estimated between 1 crore and 4 crore.

The same proportions apply to the margins of error when counting COVID-19 deaths. A journalist-friend in Hyderabad at the time indicated that the daily count of COVID-19 cases and deaths was written down by an official in a scrap and Whatsapped to reporters at the end of office hours.

Nothing remotely official about it, but those were the numbers that showed up in the evening news.

The estimated crowd sizes at political rallies – be it for Narendra Modi, Rahul Gandhi, or regional leaders – often challenge the constraints of physical geography. The deaths due to shock after YS Rajasekhara Reddy's passing in Andhra Pradesh were cited in thousands, with no verifiable records.

Statistical Politics

India is at once home to some of the world’s finest statistical institutions – ISI Kolkata, the Census Bureau, and top-tier mathematicians – while remaining strangely susceptible to miscounting. The problem, then, is not one of capability but of inclination. Joel Lee, in his book Deceptive Majority, reports how census enumerators nonchalantly miscount. They just don’t bother.

This peculiar habit of inflating or deflating numbers was a problem for the British as well. During the Raj, census numbers were often suspect, thanks to both administrative incompetence and communal anxieties.

The British spent enormous efforts to count the population correctly. In post-Independence India, the population of castes and sub-castes in official surveys became a site of political contestation, as caste-based reservations turned numerical strength into bargaining power.

The anxiety over caste census is often dismissed as the upper castes' fear of losing power. What, then, explains the methodological shortcomings of the Mandal Commission Report?

LR Naik, the lone Dalit member of the commission, dissented from the report, accusing the commission of favouring dominant backward castes. This concern was never addressed.

As the Maratha reservation struggle once again showed, reservations are the product of a political contract, rather than a fidelity to numbers and data. No evidence of backwardness was found among Marathas by the Backward Classes Commission, so another study was ordered through a different commission. Guess why.

Even internationally, numbers are often politically weaponised. China’s GDP statistics, the number of North Koreans cheering or mourning their Dear Leader, and Russia’s casualty counts in conflicts, to name a few examples, all show signs of strategic exaggeration and suppression.

However, India’s miscounting differs in that it is not always – or even primarily – state-directed. Unlike the carefully curated numbers of authoritarian regimes, India’s numerical inconsistencies are often chaotic and organically unpredictable, born out of a collective self-perception rather than a centralised will.

Of Myth and Magic

Is India’s discomfort with numbers a failure of mathematical reasoning? Unlikely. India has produced prodigious mathematicians like Ramanujan and mathematical schools like the Kerala School, and its computational sciences are globally respected.

Despite its faults, the country is successful in conducting some of the world’s largest elections, censuses, and vaccination drives.

We are surely not numerical illiterates. The trouble is with a civilisational disposition towards an extravagant anti-empiricism.

In the Advaitic school, every empirical phenomenon is maya (illusion). One Sai Bhajan goes, "Koti Pranam Shata Koti Pranam" (one crore salutations, a hundred crore salutations). Our epics describe warriors firing thousands of arrows in seconds, and gods with an unusual number of heads and multiple arms.

There are, in some religious traditions, 33 crore gods – who counted them? These fantastical elements shape the Indian imagination, allowing for an elasticity with numbers that extends to modern contexts.

The Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez consciously employs this hyperbole of numbers in his writing to give off a mythical, folkish feel, akin to grandmothers’ tales. But Indian grandmothers and grandchildren alike seem to unconsciously be under the sway of this hyperbole.

When millions throng the Kumbh, the spectacle itself feels beyond counting, so numbers swell in proportion to the collective sentiment.

Distorted Realities

One might argue that these numerical inconsistencies are trivial – a cultural quirk rather than a crisis. After all, India continues to function despite these exaggerations. But there are deeper consequences.

Distorted numbers distort policy planning, leading to distorted arrangements.

Underreporting preventable deaths, be they from accidents or from conflicts, prevents necessary safety reforms and reasonable political solutions.

Similarly, unreliable socio-economic data hampers effective governance, leading to misplaced welfare allocations and resource mismanagement.

It can also be argued that the proclivity towards exaggeration is universal –other societies too inflate attendance at rallies and protests. However, in mature statistical cultures, these numbers face rigorous scrutiny.

In India, such scrutiny is often absent, allowing guesswork, uneducated or sly, to solidify into too-quickly-accepted truths.

Ultimately, an ethical approach to counting is not just about precision; it is about respect – especially for those who perish in underreported disasters, and for the millions who are more than mere statistical props in grand narratives.

Our great numbers, of people, of pilgrims, of casualties, do not need embellishment. The truth itself is sufficiently impressive. If the Maha Kumbh drew only 10 crore people across the whole event and not just in a single day, it remains the largest human gathering ever – no hyperbole required.

(Arjun Ramachandran is a research scholar at the Department of Communication, University of Hyderabad. Kuriakose Mathew teaches politics and international relations at PP Savani University, Surat. His research focuses on democratic forces in transitional polities. This is an opinion piece. The views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)