The late historian MSS Pandian had once written an essay on how there are two competing modes of talking about caste in the Indian public sphere. When the Dalit and lower castes speak against the existing caste orders, it is magnified as fomenting conflict. But when the upper castes sidestep visible caste-based deprivations, they become unmarked universal citizens, and when they practice it in private as purity, they are banalised as carriers of harmless culture.

This asymmetric treatment extends seamlessly into the realm of Indian cinema.

Films that foreground Dalit protagonists and their negotiation and conflict with upper-caste dominance are categorised as "caste films"—or films that address “caste issues”. On the other hand, those rooted in upper-caste milieus are normalised as apolitical narratives of family, romance, or tradition. What the intelligentsia and film critics do not acknowledge is that every film that is based on a caste society has something to do with caste.

Caste in Bollywood

In recent years, there have been broadly three approaches towards caste in Bollywood:

1) Caste as 'unmarked norm' where caste society is a normal order of things with an upper-caste world and their drama and love stories.

2) Upper caste guilt wherein an upper-caste protagonist comes face to face with the helpless wretched Dalits and laments that caste exists in the 21st century.

3) The conflict and negotiations of Dalits with the caste society around them. Dhadak 2 falls in the third category of films.

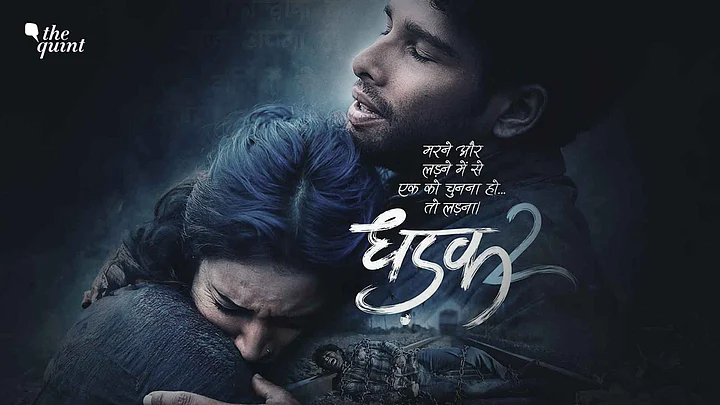

An adaptation of Mari Selvaraj’s critically acclaimed Tamil film Pariyerum Perumal (2018), Dhadak 2 localises the narrative within Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, capturing the tension of an inter-caste romance between a Dalit man and a Brahmin woman. While initial skepticism surrounded the film, given Karan Johar's production, it is Shazia Iqbal’s nuanced direction that lends credibility and depth.

Rather than reproducing a tale of abject Dalit suffering—as seen in early autobiographical works like those of Omprakash Valmiki—or veering towards an overtly Dalit political narrative singularly that might come across as caricaturing like Article 15, Dhadak 2 navigates a middle path, grounded and deeply human.

'Dhadak 2' and the Ambedkarite Hero

The film is situated in a post-1990 urban periphery where Dalits, though still engaged in stigmatised labour such as sanitation work, drumming at weddings, dance performances, and leather trades, are no longer depicted as destitute. These communities, though materially constrained, assert cultural identity through visible markers such as blue flags, portraits of Dr BR Ambedkar, and remnants of Ambedkarite mobilisations dating back to the 1980s Bahujan Samaj Party rise in neighbouring Uttar Pradesh.

Siddhant Chaturvedi’s portrayal of Nilesh Ahirwar, a Chamar youth who transitions from playing drums at weddings to pursuing law school, is a reflection of aspirational Dalit youth from the urban periphery who hope to rise up through higher education.

At the same time, he embodies the archetype of the “avoidant Dalit”— symbolic of those Dalit students who are deeply aware of their caste identity and the stigmatised areas they come from but they feel they can navigate upper-caste spaces and gradually integrate by not talking about these realities. Siddhant does a decent job in displaying his inhibitions and fear. He does not want to engage in political activism on campus and wants to focus on his studies.

His reticence in pronouncing his surname and his struggle with English highlight the imposed anxieties that many Dalit students grapple with in university spaces among proud upper-caste students.

Conversely, Tripti Dimri’s Vidisha Bhardwaj, a Brahmin woman from an upper-middle-class family, is assertive about a woman’s place in the family and in relationship with a man but seems oblivious to brute realities of caste as a thing in the past. She wants to use her privilege to help Siddhant in English, stands up for him in class, and often reminds him of the transcendental power of love after each public humiliation and physical violence that he and his father are inflicted by her family members due to their relationship.

The relationship between a Dalit man and a Brahmin woman in a caste society is one of extreme polarity in caste terms, and when compounded with class realities, it can be a skewed dynamics.

In such cases, the Dalit man goes there as a social outcast. He grapples with existential angst and worth either caused through internal relationship dynamics or external forces. He is reminded explicitly or implicitly that neither the classroom nor the relationship is his place. University spaces and formal workplaces momentarily make it seem like caste, and at times, class transgressions are possible, but gradually the realities of two distinct life worlds seep in.

Nilesh goes through this internal turmoil leading to back and forth in their relationship after every act of caste humiliation and physical violence he is met with.

In this process,his masculinity is disciplined to remain subservient to upper-caste masculinity. I would have liked to see more moments of Nilesh processing the grief—and the questions that prick his mind. I would have also liked to see his conversations with Vidisha—and how each of them understand it coming from different social positions. In the film, this process is substituted through assurance and consolation after brutal events that convey the larger point that Vidisha is confident, and Nilesh is fearful and wants to give up at times.

The portrayal is symbolic of many inter-caste relationships where humiliation of the Dalit man and the need for the Savarna woman to confront her family, which is coercive and threatening, goes hand in hand. Tripti has played her character quite well and has more agency compared to the character in Pariyerum Perumal, but we must not forget that there are also examples where dominant caste women are confined, pressurised, and quietly give into their families in Tamil Nadu.

Between Reel and Real

In many cases, this dynamic does not lead to a redemptive ending as shown in Pariyerum Perumal and Dhadak 2, especially after attempts to humiliate and kill the Dalit man. The recent gruesome killing of a Dalit techie Kavin in Tamil Nadu over inter-caste love is one such example. Even if they stay alive and get married, the upper caste/intermediary caste family and relatives do not accept it easily. It is an emotionally tense process to live with.

On the other hand, the story briefly alludes to topics of social conservatism, caste purity, and obsession over endogamy in the intimate spaces of Vidisha’s Brahmin household.

Although this is commonplace knowledge, to depict this interior of upper-caste families as regressive and not harmless cultural practices, is indeed commendable. More so, Madhya Pradesh in North India has had no large-scale disruptive social movements against dominance and oppressive practices of upper castes, unlike Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Thus, choosing Bhopal to represent this story is an important intervention regardless of the logic used for choosing the location.

The film also excels in regional rootedness.

The mention of Launda Naach on the stage where Nilesh’s father is dancing makes his representation culturally rooted rather than simply incorporating it from Pariyerum Perumal’s cultural context from Tamil Nadu. The principal of the law university with an Ansari surname, and with Ambedkar's and Phule’s portraits in his office, as well as his own admission of being taunted as a Julaha, can be seen in the context of emerging lower caste Muslim politics against caste discrimination in parts of North India.

The director’s choice to not incorporate the use of machetes by dominant castes and the final tea-sharing scene from Pariyerum Perumal is a sensible move which, though powerful in its original context in Tamil Nadu, would have seemed incongruous in the North Indian setting. Overall, Dhadak 2 is a poignant, place-sensitive, and thoughtfully crafted narrative.

If one aspect of Dhadak 2 underwhelms, it is its music. Unlike Pariyerum Perumal, whose haunting score lingers in memory, Dhadak 2 fails to evoke similar auditory resonance, a missed opportunity in an otherwise evocative film.

My take would be to watch Dhadak 2 in its own context. And that is a city in Madhya Pradesh, and not from a bit by bit comparative take with Pariyerum Perumal. The town the latter is set in is notorious for caste violence against Dalits. It also has a history of Schedule Caste communities like the Devendra Kula Vellalars responding aggressively. So, to let go of these distinct socio-political contexts and expect similar caste tensions gripping you in Bhopal as a measure for the brilliance or radicalism of the film would be a force fitting reality.

(Sumit Samos hails from South Odisha and he recently completed MSc in Modern South Asian Studies from the University of Oxford. He is a young researcher and anti-caste activist and his research interests are Dalit Christians, cosmopolitan elites, student politics and society and culture in Odisha.)