Chikankari—a traditional embroidery style from Lucknow—has been long associated with elegance and sophistication. Historically, it adorned the wardrobes of the elite, symbolising a refined aesthetic sensibility. Of late, however, it has become the new scapegoat for a peculiar kind of social disgust.

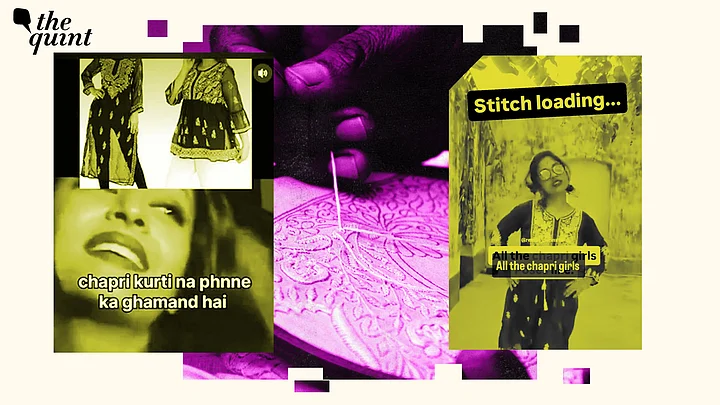

As mass production made chikankari more accessible, its perception shifted. Pastel chikankari on Khushi Kapoor in Loveyapa? “Elegant.” The same embroidery on a young woman dancing on Instagram Reels? “Chhapri.”

A new trend on social media is gaining traction, mocking chikankari kurtas as ‘chhapri’—a slur laced with class contempt and caste-coded ridicule—revealing how fashion trends are often less about style and more about maintaining social hierarchies.

The evolving contempt for the craft has little to do with the craft itself; it’s more about aspiration policing, the obsession with exclusivity, and the panic that sets in when something once ‘elite’ dares to become… popular.

The Aesthetic Anxiety of Inclusivity

Aleena, a Dalit poet, activist, and artist, calls out this trend as being a manifestation of “aesthetic anxiety” and “internalised elite panic.” When chikankari was exclusive to the upper echelons of society, it was celebrated; now that it's worn by a broader demographic, it's mocked.

Fashion trends don’t exist in a vacuum. They exist within a casteist and classist visual grammar—where aesthetics signal status, and status is policed through mockery. The second an item crosses over from the rarefied world of boutique hauls and curated feeds into street markets and fast fashion, it loses its protection. It becomes mockable.

Terms like ‘chhapri’ are aesthetic dog whistles that reinforce class distinctions under the guise of fashion advice.

Chikankari kurtas are overwhelmingly worn by women, often in soft pastels or florals—signalling a kind of delicate femininity that India has historically prized in women belonging to privileged caste and class backgrounds. Calling the aesthetic ‘chhapri,’ then, serves as a carefully coded insult to suggest that some individuals are overstepping their social boundaries by adopting styles previously reserved for the elite.

It’s also a way to control who is allowed the privilege of feeling ‘beautiful’ and ‘confident,’ by society’s standards.

This is a subtle yet insidious form of social control, being used as a tool to humiliate those perceived as too ‘lower class’ to be allowed into the temple of taste.

From Labour to Mockery: The Cruel Irony

Authentic chikankari is labour-intensive and expensive because it's handmade, making it a luxury item. But fashion—by design—trickles down and becomes accessible in mass-produced forms.

“Mainstream retailers and designers frequently leverage high-end trends to create more affordable options for a broader audience. They achieve this by utilising alternative materials, such as synthetic polyester instead of silk or cashmere, which closely resemble the originals. Additionally, they may employ different production techniques, such as power looms instead of handlooms, to reduce labour costs. Costing and pricing strategies are implemented to minimise overhead expenses and improve profit margins,” writes Shraddha Kochar, who has worked in the fashion industry for close to a decade.

“This accessibility enables consumers to purchase fashionable shoes at more affordable prices, ensuring that trendy styles are within reach for a wider range of individuals.”

This isn’t a flaw in the system; this is the system.

This begs the question: if you genuinely value the artisanal beauty of what you own, why does someone else wearing an affordable version threaten your fragile ego? It's telling that instead of celebrating how more people can now feel joy and beauty in something once exclusive, we mock them. This is capitalism, casteism, and class anxiety braided together.

Mockery as a Mechanism of Power

The violence of mockery here is active, not passive. When people are ridiculed for defying capitalist control and feeling good in something that was once gatekept, it serves as a cultural slap to remind them where they belong. And all of it, of course, is thinly veiled in the language of ‘taste.’

At the end of the day, ‘chhapri’ is about daring to express joy, sensuality, ambition, or self-worth in a body that society has decided doesn’t deserve it.

Last month, fashion commentator Diet Sabya called out people who mocked the “sudden influx of Indian celebrities” at the Met Gala, terming it the ‘Chandivalification’ of the event. “Shouldn't we be celebrating the fact that we're finally cracking the code to one of the most gatekept events of all time?” he asked.

More recently, similar criticism erupted online in India, targeting the presence on influencers on the red carpet at the Cannes Film Festival. While there is, perhaps, some merit in calling out non-film folks for using an international film festival—not a fashion gala, unlike the Met—to boost their online presence, the fact remains that, brands have been sponsoring celebrities to walk the festival's red carpet for years, as influencer-turned-actor Kusha Kapila pointed out.

The new-found disdain for chikankari follows a similar logic.

The Brutal Irony: When Artisans Become Outsiders

The sharpest irony, though, is that the very people mocked for wearing chikankari kurtas often belong to the same demographic that makes them.

Chikankari, like most artisanal crafts in India, is largely produced by workers from oppressed caste groups. A 2022 report also shows that 60 percent of chikankars (chikankari workers) are upper-lower class, while 40 percent live in poverty. Most have little to no access to formal education and “lack knowledge about [fair] wages.”

Naturally, they can’t afford to wear the very garments they spend their lives hand-embroidering. And when they—or others from similarly marginalised locations—finally can, they’re met with derision.

This is the brutal feedback loop of aesthetic casteism: marginalised communities create beauty, but are barred from enjoying it. Their labour is praised only when it's divorced from their bodies. Their designs are celebrated only when refracted through the lens of savarna influencers, luxury stores, or celebrity endorsements. And when these styles enter the mainstream, it’s the dominant-caste consumer who’s imagined as their rightful owner—not the artisan.

Heritage Without Redistribution is Just Appropriation

It’s a reflection of the same cultural appropriation at a global level that actor Janhvi Kapoor pointed out in Diet Sabya’s post: “For decades the work of our artisans has been exported from our country and put on global platforms without credit. For decades they have borrowed our fabrics, our embroidery, our textiles, our jewellery, and presented it as [their] creation.”

In the context of crafts like chikankari, that same appropriation happens domestically, but is rarely addressed in mainstream discourse—especially not by mainstream celebrities like Kapoor. Artisans are reduced to tools, their identities and struggles invisibilised, while the privileged play dress-up with their work and then ridicule them if they dare to wear it.

What’s considered ‘good taste’ is always decided by the people with the most power and the loudest platforms—in India, this has historically meant dominant-caste, upper-class people, who decided that chikankari was beautiful when it was rare and handcrafted and expensive, and is somehow tacky now since it’s being worn by ‘too many’ women, in ‘too bright’ colours, or in ‘too tight’ fits.

Platforms like Instagram amplify these dynamics, with influencers and fashion bloggers often setting the tone for what's considered ‘cool’ and what’s to be scoffed at as ‘cringe.’

The meme-ification of fashion is rarely as innocent as it seems. When influencers ridicule a woman dancing in a chikankari kurta as ‘thirsty’ or ‘chhapri,’ they’re enforcing social codes about who’s allowed to be visible, desirable, or expressive. This digital gatekeeping mirrors real-world social hierarchies, where visibility and acceptance are contingent upon one's adherence to elite standards.

The democratising potential of fashion is undermined thus by online echo chambers that reinforce exclusivity.

Fashion: A Frontier of Access and Exclusion

In a society where caste status has always been about regulating access — to water, temples, education, public spaces — fashion becomes another site of control.

To challenge these entrenched hierarchies, we need to move beyond performative appreciation of handcrafted aesthetics and confront the uncomfortable truth: most traditional crafts survive on the exploitation of underpaid, invisible artisans, many of whom are women from oppressed caste and class locations.

It's not enough to romanticise heritage while erasing the very hands that keep it alive. Recognition must come with redistribution—of credit, of money, of visibility.

Valuing chikankari means valuing the people who make it. That means fair wages, safe working conditions, and the dignity to wear their own work without being seen as ‘out of place.’ It means expanding our idea of beauty beyond savarna influencers in white-on-white aesthetics to include the bodies that have always been excluded from that frame.

Fashion, at its best, can be a canvas for self-expression, identity, and joy. But when it becomes a marker of exclusivity, used to gatekeep who gets to feel attractive, aspirational, or worthy, it stops being about style and starts being about power.

So the next time you flinch at seeing someone “not like you” wear something you love, ask yourself: was your sense of style ever really about looking good yourself, or about asserting who is—and isn’t—allowed to look good?

If beauty has to be hoarded to feel special, then maybe it was never beauty to begin with. Maybe it was just insecurity dressed up in designer clothes.

(Aleena is a poet, writer, and dalit feminist thinker from Kerala whose work explores themes of gender, sexuality, religion and caste politics.

This is an opinion piece. All views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)