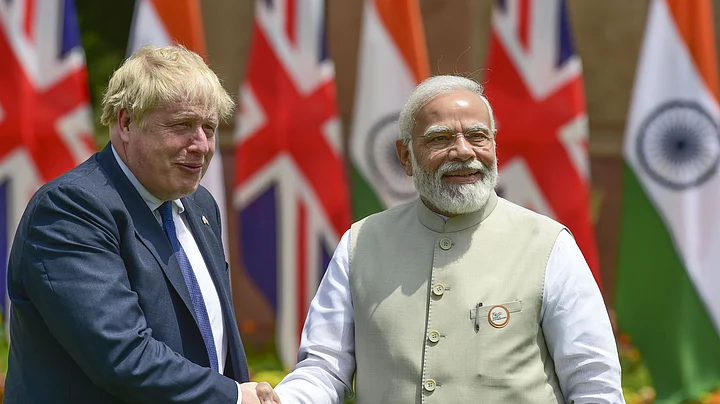

Notwithstanding the images of British Prime Minister Boris Johnson spinning the charkha in Sabarmati, his two-day visit to India is all about the UK working to cope with the self-inflicted wounds of Brexit. Having burnt the metaphorical bridges to the European continent, the UK is trying to compensate by re-establishing trade and investment links of the ‘Empire’, or, to put it more politely, the Commonwealth, now seen through the lenses of the Indo-Pacific.

An Opportune Moment

For India, the visit comes at an opportune moment. Having stayed out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and developed something of a reputation as a foot dragger when it comes to free trade agreements, New Delhi is now trying to make up for lost time.

Since the beginning of this year, it has signed a trade agreement with the UAE, an interim trade deal with Australia, and is trying to fast-track trade and investment agreements with the UK, the European Union (EU) and Canada. Now, according to Johnson, India and the UK hope to have their Free Trade Agreement (FTA) by Diwali.

Also, with its relationship with China settling into an uneasy antagonistic face-off, New Delhi, which is a key member of the Quad, is happy to link up with the UK, which in 2021 made a decisive move to become part of the anti-China military alliance in the region, AUKUS.

The UK is the fifth-largest economy in the world, and its capital, London, is a global financial hub. It is also a major science and technology innovation centre, with world-class universities. All of these make it an important partner for a country like India.

The current momentum in the relationship has been built since the Modi- Johnson virtual summit in 2021, which launched a 10-year roadmap focusing on five areas towards a “comprehensive strategic partnership” – health, climate change, people-to-people contacts, trade and investments and defence and security.

Trade, Investment, Defence: What the Visit Was All About

The core issues taken up during the Johnson visit are trade, investment and defence ties. The two countries hope to sign a trade deal that would cover 65 per cent of goods and some 30 per cent of their bilateral services trade. They expect that with a comprehensive trade agreement, they should be able to double their trade by 2030. Two-way trade is currently around $50 billion – 70 per cent of it is services and the balance are goods.

For that reason, the visit was about enhancing business links and creating partnerships in areas such as software engineering, science and technology, and health. India will host the third round of discussions for the FTA with the UK from 25 April.

According to a press note from the British High Commission, Johnson discussed next-generation defence and security collaboration “across five domains” of land, sea, air, space and cyber. The UK has expressed interest in assisting Indian fighter jet and helicopter programmes and collaboration in the undersea battlespace. To support these endeavours, Johnson announced that the UK will issue an Open General Export Licence (OGEL) to India that will make access to technology and acquisitions easier.

India & UK's Shared Interests

With the UK's focus on the Indo-Pacific, there is a natural congruence between the interests of India and Britain in “an open, free, inclusive and rules-based Indo-Pacific region”. The UK is hoping to make a major push in the area of defence trade. But to do so, it will have to seriously address New Delhi’s interest in promoting its domestic arms industry.

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi noted, India welcomed British support to its defence self-reliance programme “in the areas of manufacturing, technology, design and development”. Besides, as the joint statement issued after the visit notes, their respective defence science establishments hope to “deliver advanced security capabilities” through joint research, co-design & development of key military technologies. A special area here is a joint working group on naval electric propulsion systems

UK Understand's India's Ukraine Stance

The focus of their geopolitical collaboration is their commitment “to a free, open, peaceful and secure cyberspace” through the India-UK cyber security partnership. Details of this were made available through a separate Joint Cyber Statement outlining the areas of collaboration in cyber governance, deterrence and resilience.

No doubt the subject of Ukraine would have been discussed. But it was made clear at the outset that it would not be a major focus of the visit. Johnson did refer to “the threats of autocratic coercion” that have grown around the world, but that was in passing.

The British government made it clear that they understood that there were differences between Johnson’s own hawkish support for Ukraine and Modi’s adherence to a somewhat neutral stance that calls for cessation of hostilities and dialogue.

India is the second-largest investor in the UK, and not surprisingly, the visit has been used to announce a series of additional investments worth GBP 1 billion in a range of areas from electric buses to robotic surgery and artificial intelligence. In addition, partnerships have been announced in areas such as climate and energy, healthcare systems and vaccines. The UK has offered its offshore wind technology system and the two countries plan to collaborate in the Hydrogen Science and Innovation hub.

Prime Minister Modi noted that the 1.6 million citizens of Indian origin in the UK were like a “living bridge” creating a special bond between the two countries. As of now, the two countries have worked their way around the contentious visa issue and Indian skilled workers are benefiting from the new points systems put in place by the UK. In his remarks on the eve of the visit, Johnson indicated some more room here when he noted that the UK had a shortage of IT professionals and programmers.

(The writer is a Distinguished Fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. This is an opinion article and the views expressed are the author's own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)