Is worship in a mosque essential to the religion of Islam? Is it so essential that it is a fundamental right protected under Article 25 of the Constitution?

These are in essence the two questions which were sought to be agitated by the parties in the ongoing Babri Masjid title dispute before the Supreme Court. The crux of the debate revolved around the interpretation of a few paragraphs of the Supreme Court’s judgment in Dr Ismail Faruqui v Union of India which seemed to have something to say about the matter.

Misunderstanding or Manoeuvre?

The positions taken by the respective advocates for the parties were not exactly what you’d expect - Dr Rajeev Dhawan appearing for the Muslim petitioners in the case contended that Ismail Faruqui said that a mosque was not an essential part of Islam whereas the K Parasaran and CS Vaidyanathan appearing for the Hindu respondents argued that it did not necessarily do so.

Logically, one would think it would be the other way round with the petitioners stressing Ismail Faruqui said that a mosque was not essential to Islam and vice versa.

Too busy to read? Listen to this instead.

One reason perhaps was to pre-empt the court from relying on the judgment at all in the eventual decision in the case. If this was indeed the case, it has worked exactly as intended

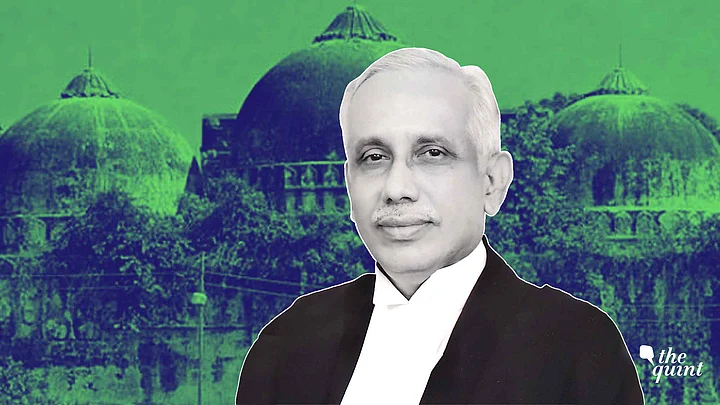

The Supreme Court’s majority judgment in M Siddiq v Mahant Suresh Das (authored by Justice Ashok Bhushan on behalf of CJI Dipak Misra as well) delivered on Thursday clarified that the Ismail Faruqui judgment said no such thing.

In understanding why the majority judgment said what it did, we need to see the context in which the judgment in Ismail Faruqui was delivered. In Ismail Faruqui, the court was concerned with (among other things) whether a mosque could be acquired by the Government through a land acquisition law. To this extent, Bhushan and Misra are right in narrowly reading Ismail Faruqui’s observations. This also means that the Allahabad High Court’s judgment under appeal will now be scrutinized as to whether it wrongly relied on Ismail Faruqui for some of the conclusions that it did. They don’t decide one way or another, but leave it to be decided in subsequent hearings.

The majority also turns down Senior Advocate Raju Ramachandran’s plea to refer the case to a larger bench nonetheless given the magnitude of issues involved. Here they take a narrow view of what would be necessary and sufficient to refer a matter to a larger bench and don’t find that the importance of the issues raised in the Babri Masjid land dispute fit these parameters. The judgment ends on a “parties are advised to chill” note but couched in much better rhetoric and language.

Voice of Dissent

But, remember, this was not a unanimous judgemnt - Justice Abdul Nazeer dissented from the majority but only one real point. Even though he doesn’t say so explicitly, he agrees with the majority that the judgment in Ismail Faruqui does not lay down that a mosque is not an essential part of Islam. He notes that the evidence which is required to arrive at the conclusion that a mosque is or is not an essential part of the Islamic religion have simply not been gone into in that case.

Nazeer’s real ground of dissent however is whether the Ismail Faruqui judgment influenced the Allahabad High Court’s judgment in arriving at the conclusions it did in respect of the Babri Masjid land. Given the reliance that was placed on the observations in Ismail Faruqui which were relied upon the judges in the Allahabad High Court, Nazeer feels that it needs to be reconsidered and harmonised with other judgments on the issue of what is essential to a religion and therefore protected under Article 25 of the Constitution.

The Importance of Being Babri

While that may or may not be a reason to refer the matter to a Constitution Bench (and one can say that the majority judgment has effectively “read down” Ismail Faruqui’s observations), Nazeer has a valid point on the significance of the Babri Masjid case necessitating a reference to a Constitution Bench. Whereas the majority did not find any constitutional question or conflict between three judge benches to refer the case to a larger bench, Nazeer accepts Ramachandran’s argument that the importance of the case itself is enough to get it referred to a larger bench. He cites instances of other cases (notably the use of public parks for Ram Leela and the khatna cases) where questions concerning religious practices were referred to a larger bench.

Nazeer doesn’t quite say it but what he means is this - a case whose long, tortured history has ripped up India’s secular fabric so badly deserves to be heard and decided by a bench which is cognizant of this.

That a case such as this has a bearing on India’s constitution even if it doesn’t actually interpret a particular provision of the article. That the Supreme Court is in an unenviable position in adjudicating this case and it must merit a full debate and discussion among enough judges to give it the credibility it needs in deciding this case.

Without reducing Nazeer purely to his religious identity, perhaps one can say that it’s that which makes him profoundly aware of the importance of this case not just for the parties or the Supreme Court but for the future of India as well.

(Alok Prasanna Kumar is an advocate based in Bengaluru, an Executive Committee Member of the Campaign for Judicial Accountability and Reforms. This is an opinion piece. The views expressed are the author’s alone. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)