As Delhi gasps for air, Chief Minister Rekha Gupta, along with Delhi Environment Minister Manjinder Singh Sirsa, have been hyping up cloud seeding as the ultimate fix of the city's pollution crisis.

Last week, the state government jointly conducted a test run with the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Kanpur, using a Cessna light aeroplane over Burari in North Delhi, to check the "readiness and endurance" of the aircraft and to assess the capability of the cloud seeding fitments and flares, Sirsa said in a statement on Thursday, 23 October.

The same day, Chief Minister Gupta predicted,

“If conditions remain favourable, Delhi will experience its first artificial rain on 29 October.”

It was then reported on 28 October that the government had "successfully" carried out two cloud seeding trials in parts of Delhi, but with no rains that followed, IIT Kanpur Director Manindra Agarwal called the attempt "not completely successful" the next day.

In the meantime, Delhi is covered in a smoky haze, with AQI readings above 300 ("very poor") in at least 23 of the city's 38 monitoring stations.

In theory, cloud seeding sounds rather simple. A chemical is sprayed from an aeroplane into clouds to induce rains. But, for climate journalists, it has increasingly become a menace—co-opted as a supposed climate fix to deflect responsibility for climate action or a tool to deny the reality of climate change, depending on the agenda.

The Quint breaks down three common claims around cloud seeding that twist climate truths.

Claim 1: Cloud Seeding is a ‘Climate Fix’

Chief Minister Gupta on 24 October told media channels that cloud seeding is a “necessity” for Delhi which will be able to “overcome its environmental problems”.

How true is this claim?

Cloud seeding enhances precipitation by injecting clouds with particles like silver iodide, potassium chloride, and sodium chloride that act as "ice nuclei". But, as Somnath Baidya Roy, Professor at IIT Delhi's Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, explains to The Quint,

“Cloud seeding can provide a nudge so that some types of clouds in some regions produce rain.”

But it “cannot conjure rain out of thin air,” as Baidya Roy notes. “It cannot produce rain if the atmospheric conditions are not conducive. If there is no moisture and clouds in the sky, cloud seeding will not work, however hard we may try. In other words, cloud seeding will work for some people sometimes, but not for everybody all the time.”

For instance, the Delhi government’s cloud seeding project has faced multiple delays, including in the third week of October, due to unfavourable weather conditions. Incidentally, the worst smog episodes in Delhi occur during winter, when the atmosphere is dry, with fewer rain-bearing clouds. Without moisture and clouds, cloud seeding cannot work.

Beyond its logistical challenges, the impact of cloud seeding is “temporary” at best—and it cannot be an answer to a serious and prolonged environmental concern as air pollution in Delhi, say experts.

“We must look out for two things. First, how much rain will cloud seeding produce? It will require a lot of rain to wash out all pollutants from the dirty Delhi air. Second, can cloud seeding be done frequently? Studies by my colleagues at IIT Delhi show that the effect of rainfall lasts only a couple of days after which the air again becomes dirty. To ensure clean air, we may have to do cloud seeding every 2-3 days. If that is not possible, cloud seeding will only provide temporary relief at best.”Somnath Baidya Roy

Experts say calling cloud seeding a "necessity" deflects the need for a systemic overhaul required to effectively combat pollution. Professor Shahzad Gani and Krishna AchutaRao from the Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, writing in The Hindu newspaper, called it “just another gimmick in a series of similar unscientific ideas, like smog towers, suggesting that flashy interventions can substitute for serious, structural solutions.”

Talking to The Quint, Gani adds,

"It is also expensive, and when cloud seeding is proposed for air pollution reduction—such as in Delhi—it will not work because the necessary atmospheric conditions are usually absent during the most polluted winter months. As a result, many scientists view cloud seeding as a poor use of limited public resources when more reliable pollution-control measures are urgently needed."

The estimated cost of Delhi's five cloud seeding trials is Rs 3.21 crore.

The bottom line then is to effectively reduce air pollution by cutting emissions from vehicles, industry, construction, power plants, and stubble burning. Experts who The Quint has spoken to in the past have said the solution lies in “a governance model with clear accountability for regulators at city, state, and national levels to ensure measurable, sector-specific reductions.”

In summation, cloud seeding cannot be the solution to the capital's pollution problem, no matter how much the Delhi government would want the people to believe otherwise.

Claim 2: Cloud Seeding Causes ‘Large-Scale Devastation’

Another aspect of cloud seeding is its scale and effectiveness. Under the right conditions, cloud seeding can increase precipitation by about 10-15 percent in localised areas. However, climate denialists often distort that scientific truth.

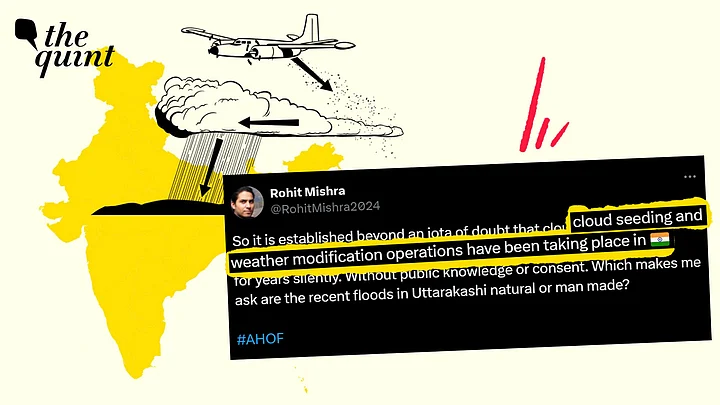

In August 2025, an X user @RohitMishra2024 shared a video of what looked like a runaway submerged under water, with airport staff surrounding the front wheel of an aeroplane. He claimed, “Flights are stranded due to heavy waterlogging at Mumbai Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Airport, India.”

When The Quint ran a verification check with a simple reverse image search using Google Lens, we found the video was neither from Mumbai nor from August when the city saw torrential rains. It was an old clip from December 2023 when the Chennai International Airport was left flooded after incessant rains triggered by Cyclone Michaung.

The user further added, “Normies will say this is natural rainfall but we know what's up. This is the result of weather modification, cloud seeding.”

This claim is part of the larger narrative of linking cloud seeding to extreme weather events. Similar claims were also made when torrential rains ravaged parts of Uttarakhand, Jammu, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, and West Bengal earlier this year, with “weather modification in action”—and not climate change—being attributed to cloudbursts and flash floods.

However, Gani explains to The Quint, "There is currently no reliable scientific evidence that cloud seeding can trigger large, destructive rainfall events." He adds,

"Cloudbursts and widespread floods are driven by strong natural weather systems—especially in mountainous regions where moist air is rapidly lifted. Even under favourable conditions, the impact of cloud seeding is usually small, localised, and hard to distinguish from natural variability."

In a June 2025 statement by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) on weather modification, the specialised UN agency had made a similar observation. The fact sheet read, “The energy involved in weather systems is so large that it is impossible to create cloud systems that rain, alter wind patterns to bring water vapour into a region, or eliminate severe weather phenomena.”

“Weather modification technologies that claim to achieve such large-scale or dramatic effects do not have a sound scientific basis and should be treated with suspicion.”WMO

Gani further adds, "Weather systems are highly variable, so it is very difficult to determine whether any rainfall that occurs was caused by seeding or would have happened anyway. This opens the door to speculative claims and oversimplified explanations for complex weather events."

Such speculative claims had particularly surged when cloud seeding was linked to Dubai's record-breaking rainfall in 2024 by conspiracy theorists. Ever since, flash floods and hurricanes, especially in the US, have fueled similar reactions.

This is despite climate scientists confirming that Dubai's heavy showers were driven by climate change, and not cloud seeding.

A scientific study published in Science Direct, which used high-resolution atmospheric data to analyse the events of 16 April 2024, found that the intense precipitation was driven by a strong cyclonic circulation, enabling moisture convergence from surrounding seas.

The study titled “Dubai's record precipitation event of 16 April 2024 – A diagnosis” also made the following observations:

…cloud seeding operations typically do not lead to such widespread, large-scale extreme precipitation events

Scientifically confirming these claims based on a single incident with limited data is challenging. But, in this case, the cloud seeding hypothesis can be dismissed since other locations in the Persian Gulf, such as Oman, Bahrain, Qatar, and Iran, reported rainstorms and flash floods around the same time.

…the UAE National Centre of Meteorology, which manages cloud seeding operations, confirmed that no cloud seeding missions targeted the storm.

“We have already warmed up to 1.48 degrees Celsius since the pre-industrial age. As we are warming up, more and more moisture gets accumulated in the air. The El Nino effect compounds on this and creates conditions of heavy precipitation,” Anjal Prakash, Clinical Associate Professor (Research) and Research Director Bharti Institute of Public Policy, Indian School of Business, had earlier told The Quint.

Claim 3: Cloud Seeding is a 'Safety Hazard'

Despite all its limitations, over 50 countries are said to be experimenting with cloud seeding to help alleviate droughts, enhance water security, and increase snowpacks. In India, it has been used for decades—primarily to manage droughts in dry areas—by states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Andhra Pradesh. In Thailand and Russia, it has been used to even suppress wildfires. In the UAE, it has been used to battle extreme heat.

However, online users who view climate seeding as a method of weather control often raise alarms about the safety of the chemicals involved. For example, an X user @Tboo211 claimed in April last year that silver iodide can cause severe burns.

However, multiple climate scientists note that quantities of silver iodide used in cloud seeding is minimal, and hence is safe for humans. For instance, the ratio of silver iodide used in the mixture to induce rain in Delhi on 28 October was 20 percent, with the remaining 80 percent composed of rock salt and common salt, according to IIT Kanpur Director Agarwal.

However, there's still a need for a thorough understanding of its long-term effects. A 2016 study published in Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety found that when cloud seeding is carried out in a specific geographical area multiple times, it could "moderately affect" the flora and fauna in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Other experts have flagged that it can potentially contaminate soil and affect groundwater quality.

As a polarising subject, the jury might still be out on the effectiveness of cloud seeding and its long-term impacts. But politicising the issue and spreading misinformation only stall progress and divert attention from the urgent climate actions needed—from building resilience and advancing mitigation measures to improving forecasting and strengthening disaster preparedness.

At the same time, it makes things harder for climate journalists, who are often left defending the reality of climate change.

So, whether cloud seeding is framed as a miracle cure or misused to cast doubt on climate science, it's climate action that loses.

(This article has been published as part of the Danida Fellowship Programme on climate reporting.)