Chess is unapologetically lugobriphilous – it derives pleasure from gloom. An enigmatic paradox for those romanticising melancholy.

How could a sport so placid, so prosaic – where a single move can take nearly an hour to manifest, and commentators and spectators alike find amusement in decoding facial expressions – concomitantly be so brutal, so remorseless, that a second’s fallacy would completely decapitate hours of unrelenting resilience?

Ding Liren had played 634 moves – most of them unerring – prior to his blunder, in the last match of the 2024 World Chess Championship.

For thirteen-and-a-half gruelling games, he held his demons at bay – dysphoria, sleep deprivation, mental burdens. Yet, on the 55th move, his sufferance barrier had reached its saturation point.

One wrong move – 55Rf2 – and the curtains fell on his battles. The bottom line – Ding Liren had lost.

Could this match not have had a – for the lack of a more respectable term – loser?

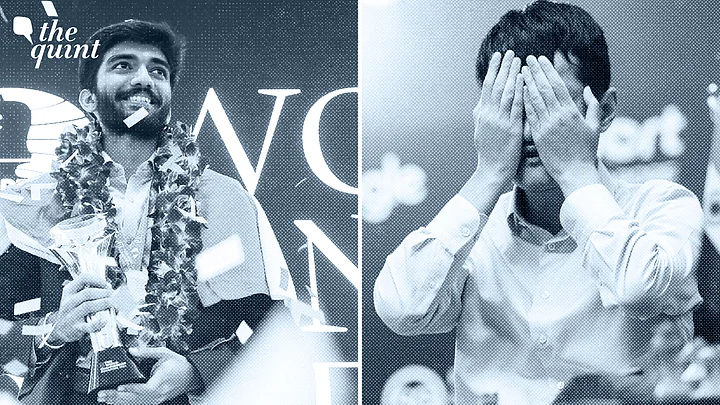

Perhaps, it could not, for as cruel as it is, chess demands a victor. And no one was more deserving a victor than Dommaraju Gukesh – all of 18, hailing from Viswanathan Anand’s Tamil Nadu, flaunting the audacity of doing what no one has in the history of this competition.

Having only recently earned the right to cast his vote, Gukesh had now earned the right to call himself the sport’s youngest-ever world champion. The Kasparovs and the Carlsens of the world could not do that.

But let us, only for a moment, look beyond the result. In a bizarre amalgamation of beauty and brutality, the World Chess Championship offered more than a victor – it offered a masterclass on life.

Chess, in all its glory, remained achingly beautiful and heartbreakingly cruel.

Gukesh’s Art of Being Chivalrous in Triumph

Perhaps, the singular most profound lesson was not about strategy, but about how the two Grandmasters conducted themselves.

Gukesh, the master of poker face, is at his inscrutable best on most days. Not on 12 December, though.

He could barely conceal his surprise following Ding’s blunder. What commenced as pure shock rapidly translated into excitement. He knew he had achieved his childhood dream. By move 58, he had deserted his chair and started pacing the hall with an aura of unflinching confidence. The sigma walk – as Gen Z would tell you.

And yet, what transpired next was anything but ‘sigma.’

As a despondent Ding stretched his hand – not to negotiate a draw on this occasion, but to concede defeat, and subsequently, the title – Gukesh knew better than not to exude his excitement. Instead, he offered a courteous smile.

Not the egoistical you-are-no-longer-the-best smile. But the graceful you-are-still-a-champion smile. In fact, Gukesh even applauded Ding as he left the hall.

It was not merely an act. In the press conference, before he spoke about what the victory meant to him and India, he acknowledged his opponent’s efforts.

Before I talk about anything else, I want to talk about my opponent. We all know who Ding Liren is. He has been one of the best players in history for several years, and to see how much pressure he faced, and the kind of fight he still gave at the world championship, it shows what a true champion he is. I’m really sorry for Ding and his team, and I would like to thank him for putting on a show.D Gukesh

But Gukesh did not stop at that. Rather, he went on to call Ding his ‘real inspiration,’ considering how his Chinese counterpart fought – both on the 64 squares, and inside his head.

What I learned from Ding is what an incredible fighter he is - true champions fight until the very end. Ding is the real inspiration for me. Champions always step up when the moment comes. He has not been in great shape for the past two years but he came here. He was obviously struggling during the games and wasn’t physically the best but he fought in all the games and fought like a true champion and I am really sorry for Ding and his team. They put on a great show.D Gukesh

What Chess Teaches Us About Perseverance

That, Gukesh was not vainglorious at the zenith, and even conscience-stricken by his opponent’s defeat, mirrors the essence of his journey.

From the moment he became the world’s third-youngest Grandmaster at just 12, the stars seemed aligned for Gukesh to scale chess’s loftiest peaks. Yet, the summit of genius often masks a treacherous descent. Barring Gukesh and Magnus Carlsen, none of the 16 Grandmasters who became a GM before turning 14 went on to earn the World Championship title.

Gukesh wasn’t even a favourite to win the Candidates Tournament, much less the World Championship. In fact, around this time last year, Gukesh’s participation in the Candidates was shrouded in uncertainty. He was staring at his last opportunity to qualify – the Chennai Grand Masters, which he had to win.

Gukesh did.

Then came the Candidates, where Gukesh, till Round 12 of 14, was trailing behind the tournament’s defending champion, Ian Neponmiachtchi. He had to win at least one of his remaining two matches.

Gukesh did.

With Ding’s troubles being extensively documented, and the erstwhile champion himself voicing his fears of facing a crushing defeat, Gukesh, despite his youth and relative inexperience, was now considered the likelier victor.

The nation was jolted awake from its hallucinatory optimism when Ding, playing with black pieces, won the first match. It was his first victory in classical chess after 304 days.

For most, it would be a deflating experience. For Gukesh, it was a propellant. Rather cheerful after his defeat, he claimed that the result only meant the battle would be ‘more exciting!’

He never looked out of ideas ever since. Indeed, he did lose another match, but was never shy to take risks. Thrice did Ding offer a draw that Gukesh rejected. Twice it led to disappointment – but the third time, it led to glory.

He had harboured the dream of becoming a world champion for ten years, and, like in an old interview with ChessBase India, had always been forthright about his dreams.

It was not a dream anymore. It was the reality. Chess taught us perseverance trumps all obstacles. Dommaraju Gukesh was at the zenith.

Ding Liren’s Act of Being Graceful in Defeat

But where was Ding Liren?

A day prior to the fourteenth match, Ding was asked about what he would do if he were to be crowned a two-time world champion. The context of his previous triumph prevented him from smiling after beating Nepomniachtchi. Emanating his usual humility, he said he would, most certainly, smile on this occasion.

He did not. He could not. For all that he had done, for every mental, physical and psychological battle that he had to endure, a naïve error in judgment ruined his endeavour.

A cruel twist of fate – the harshest conclusion to an otherwise heroic campaign. But there was nothing harsh about Ding’s own assessment of the outcome.

Rather, he acknowledged Gukesh’s victory by stating:

Considering yesterday’s lucky survive it’s a fair result to lose in the end. I have no regrets.Ding Liren

Indeed, chess taught us how perseverance trumps all obstacles, yet it does not warrant victory. In chess, like in life, for every success story, there is a tale of dismay. For every dream realised, there is an account of disillusionment.

For every winner, there has to be a loser. But whether one wants to be a graceful loser or a bitter one depends on individual preferences, and Ding chose the former.

Individuals like him know to how relinquish the crown with poise.

Perhaps, he might have hummed lines from Chris de Burgh’s song ‘The Snows of New York’:

“There are those who fail, there are those who fall

There are those who will never win

Then there are those who fight for the things they believe

And these are men like you and me.”