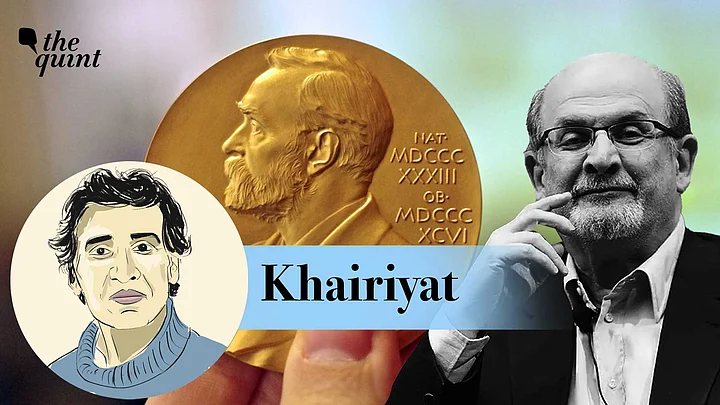

The attack on Salman Rushdie on 12 August 2022, which resulted in grievous injuries to the renowned novelist, changed my opinion on one matter: I now believe that Rushdie should be given the Nobel Prize for Literature.

There is no doubt that Rushdie is one of the most significant writers of our age. Nevertheless, I have not been a great fan of his writing. This, obviously, does not reduce the quality of his work.

I can see that his fiction is striking in many ways, and there is no doubt that Midnight’s Children opened up many avenues for South Asian writing in English. However, the style attributed to him and writers like him—‘magic realism’ —holds little appeal for me.

I feel despite the fact that Western publishers still love to see non-Europeans adopt that dazzling style, ‘magic realism’ by that or any other name, outlasted its welcome sometime in the 1990s.

Rushdie’s Treatment of Magic Realism

But Rushdie started well before the 1990s, and one cannot deny the originality and significance of at least four of his novels, despite whatever religious objections one might have to one of them.

I say so, though there is only one novel by Rushdie that I can read again and again: Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990). This might be so because the increasing monotony of the brilliance of ‘magic realism’ as a genre shades into a stronger genre: serious ‘children’s writing’, with its roots in the folk tales retrieved and propagated later as ‘fairy tales’ by people like the Grimm Brothers, and the eccentric experimentation of literary writers like HC Andersen and Lewis Carroll.

I have had many problems with what is termed ‘magic realism.’ For instance, I am not convinced that it, in any way, opposes the so-called ‘Cartesian certainties’ of European colonialism, which often attributed reason only to Europeans or European tutelage. I also do not believe, as the great Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier claimed in 1949, having recently returned to South America after years in Europe, that a mixture of the ‘marvellous and the real’ is a characteristic of South America, and, by inference, the rest of non-Europe.

Actually, I can find a number of European texts, well into the twentieth century, that do so too without the slightest hesitation, and one can convincingly argue that such a mixture is probably a feature of all cultures where orality dominates or continues to impact significantly on high literacy.

It could be that the mixture of facts and fiction that is increasingly a distinctive aspect of public life in the internet era is a consequence of the return of ‘orality’ through electronic and digital channels and the diminishment of high literacy, at least as in print culture.

An Absurd Amalgam of Fiction & Facts

While I believe as strongly as Carpentier and Rushdie in the role of ‘creolisation’ in culture, I do not feel that magic realism automatically champions this. I fear that by making immaterial the dissonance between what people consider real and what they consider magic, it performs a neat trick of comfort in which the difference between the self and the other disappears. This can be easily appropriated by reactionaries too.

In that sense, I prefer harder surreal texts, or Gothic fiction, which addresses the matter of difference. The ‘supernatural’ absorbed into the ‘natural’, the magic as an nonreducible and normal part of the real: these are comfortable ideas, and they evade the fact that when difference erupts, what it creates is not just the possibility of friendship but also threat and danger, as Emmanuel Levinas correctly pointed out. I prefer texts in which the other does not lose its difference, which can evoke friendship or fear. In that sense, I feel Gothic fiction does a better job than magic realism.

Finally, however, I find magic realist texts boring to read now. This was not the case until the 1990s. There was a freshness and originality to the texts produced by the great Gabriel Garcia Marquez and others, and also to the early texts of Rushdie and Haruki Murakami. But, now, there seems to be a repetitiveness that reminds me of those heavily philosophical ‘literary novels’ that were being written in the 1960s and 1970s in the wake of Jean-Paul Sartre: a freshness turned into a habit.

This is the reason why I can no longer read new novels by Rushdie or Murakami. But this does not mean that they are not good novels. It just means that some readers and writers, like me, differ in our opinion of them. One can argue that we are wrong. One can even prove it using market statistics: not only does ‘magic realism’ sell much more than the kind of fiction we write, it is obvious that Rushdie and Murakami sell thousands of copies more than I do.

I put on record my literary unease with Rushdie’s later writing and the entire style associated with him in order to illustrate that I am not one of his many swooning fans. And yet, I urge the Nobel committee to give him the Nobel Prize.

Now. As a writer, he has done as much as many others to whom the Nobel has been offered. As a person and a writer, he has suffered much more and stood by his principles: “But what is the point of giving persons Freedom of Speech,” declaimed Butt the Hoopoe, “if you then say they must not utilise same?” It is time to tell all those who stand with stones on the other side of the divide, saffron stones, green stones, and dollar stones, that we can take a stand too. Give Rushdie the Prize!

(Tabish Khair, is PhD, DPhil, Associate Professor, Aarhus University, Denmark. He tweets @KhairTabish. This is an opinion article and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)