(This piece was first published on 14 November, 2025. It is being reposted in light of 150 years of Vande Mataram and the debate in the Lok Sabha about the same.)

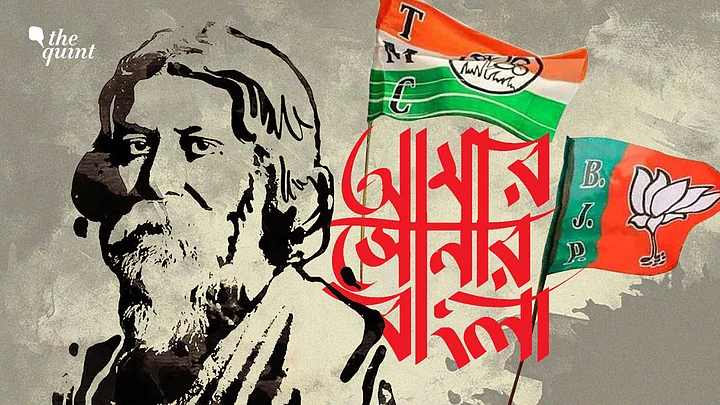

In West Bengal, politics and poetry often blur. And the latest storm over authors Rabindranath Tagore and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay reflects how the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) still fails to catch the political pulse of the state.

Bengal’s cultural identity has always been expansive, not exclusionary. From Bankim and Tagore, to Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Kazi Nazrul Islam, Bengal reveres its icons for their secular intellect, not religious ideology. In homes across the state, children grow up singing both Rabindrasangeet and Nazrul Geeti, a reflection of Bengal’s pluralistic and self-assured cultural soul.

However, political opportunism is attempting to fracture this harmony as elections draw near. The BJP's attacks on Mamata Banerjee for promoting Tagore’s Amar Sonar Bangla—also Bangladesh’s national anthem—reflect a shallow understanding of Bengal’s emotional landscape. Imported from Delhi's playbook, these debates alienate Bengali voters and bolster Mamata's position within the state.

Local BJP leaders privately acknowledge that subnational pride cannot be countered through cultural confrontation. Yet, Delhi’s overreach and Hindi-centric politics keep earning the BJP the “anti-Bengal” tag—a narrative that Mamata has turned into her most potent weapon.

The Shared Songs of Bankim and Tagore

As the Centre marked 150 years of Vande Mataram, Prime Minister Narendra Modi accused the Congress of “tearing” the song in 1937—saying that truncating its verses “sowed the seeds of India’s division.”

The West Bengal government’s simultaneous order making Tagore’s Banglar Maati Banglar Jol compulsory in schools added fuel to the fire, letting both the BJP and the Trinamool Congress turn Bengal’s poets into political flags.

What is conveniently forgotten is Tagore’s own decisive role in 1937—not the Congress diktat—that shaped Vande Mataram as India knows it today.

When Jawaharlal Nehru sought his counsel amid protests from Muslim leaders, Tagore argued that only the first two stanzas, celebrating the motherland’s beauty and benevolence, should be sung.

The latter parts, tied to the Anandamath novel’s militant imagery, he warned, could wound communal sensitivities. It was Tagore’s moral reasoning—not political compromise—that preserved Vande Mataram as a national song of unity, not exclusion.

Yet today, political camps are weaponising both poets. The BJP casts Bankim as its cultural totem; the Trinamool responds by wrapping itself in Tagore’s aura. But both writers embodied a nationalism far broader than any party’s narrative—one rooted in devotion, dignity, and pluralism. Reducing them to partisan proxies betrays Bengal’s own intellectual soul.

Bangladesh may chart its own path, tinged with Islamist hues and Indo-Bangla tensions, but culture defies borders. The Bengali language's lilt, folk melodies, and poetic pulse bind West Bengal and Bangladesh indelibly. Denying this in nationalism's name is not patriotism—it's amnesia.

In November, West Bengal mandated Banglar Maati Banglar Jol in state schools, echoing its 2023 state anthem decree. Overlooked: this Tagore gem underpins Bangladesh's Amar Sonar Bangla. Both anthems are rooted in Bengal's soil, water, and soul—transcending maps. Irony peaked in Assam, where a Congress leader faced charges for singing Amar Sonar Bangla on CM Himanta Biswa Sarma's directive. Kolkata erupted: intellectuals and students defiantly chorused the tune. Politics divides; culture unites.

Tagore's legacy is no liability—it's civilisational treasure, claimed by the Padma's banks, not flags. Embracing this bolsters India's confidence. To be Bengali is to echo Rabindranath's verse in the people's eternal refrain—borderless, timeless.

Unease in Saffron Ranks of Bengal

In Bengal, the BJP faces a problem not of numbers, but of narrative. The party that once rode high on the momentum of 2021 is now splintered by internal rivalries and an identity crisis it never resolved. Suvendu Adhikari, the Leader of Opposition and the party’s most visible face in Bengal, remains both its biggest asset and its deepest faultline.

Once Mamata Banerjee’s protégé, Suvendu’s shift to the BJP brought electoral gains, but his Trinamool-honed populism and non-RSS background have alienated sections of the BJP’s old guard and ideological purists.

The deeper trouble, however, lies in the BJP’s failure to understand Bengal’s subnationalism—an emotive blend of linguistic pride, cultural memory, and historical trauma. The recent attempt to invoke Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay against Tagore, and to question Mamata Banerjee over Tagore’s Amar Sonar Bangla, has only reinforced the Trinamool’s portrayal of the BJP as “anti-Bengal.”

In a state where cultural pride is politics, the BJP’s Hindi-Hindutva idiom clashes with the Bengali psyche.

Compounding this are anxieties among the Matua and Rajbanshi communities—Hindu refugees who migrated from Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) and form a key part of the BJP’s vote base. Their hopes were pinned on the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), but the law remains unimplemented. Many now fear disenfranchisement under the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) process, since CAA documents don’t count as citizenship proof. These are not fringe groups—they are the BJP’s backbone in border districts.

Caught between Delhi’s command and Bengal’s cultural conscience, the BJP finds itself politically adrift. Its biggest opponent today may not be Mamata Banerjee—but its own misreading of Bengal’s soul.

As the 2026 Bengal Assembly polls draw closer, cracks within the BJP's Bengal unit are no longer whispered—they are now public and pointed. A section of senior Bengal BJP leaders, including former State president and ex-Tripura Governor Tathagata Roy and Calcutta High Court judge-turned-MP Abhijit Ganguly, have openly criticised the party’s Delhi leadership for what they call a “Hindi-speaking” takeover of Bengal politics. Their frustration captures a growing sentiment—that the BJP’s national command neither understands Bengal’s political grammar nor respects its cultural idiom.

Abhijit Ganguly recently stated bluntly that Mamata Banerjee cannot be defeated by “non-Bengali speaking leaders who fail to grasp Bengal’s emotion and pride.” Tathagata Roy has gone further, blaming the Delhi heavyweights for the BJP’s 2021 defeat, arguing that Bengal’s campaign was hijacked by outsiders unfamiliar with its pulse. Their critique exposes a truth Delhi has refused to acknowledge: Bengal’s politics is inseparable from its subnational identity—a blend of language, culture, and historical self-respect.

The BJP’s central leadership, however, continues to commit avoidable missteps. Bengal co-observer Amit Malviya’s remark that “there is no language called Bengali,” the recent Bankim vs Tagore debate, and the controversy over singing Amar Sonar Bangla, all reveal a tone-deaf approach that alienates Bengali voters. Instead of letting local leaders frame a culturally rooted campaign, Delhi’s dominance has imposed a homogenised Hindi-Hindutva template that simply doesn’t translate in Bengal.

The result is a backlash not from Mamata’s camp, but from within the BJP’s own ranks. Bengal BJP leaders now openly warn that unless the central leadership allows the state unit autonomy to speak in its own voice, linguistically and politically, the party will continue to lose both relevance and credibility. In Bengal, identity is politics; ignoring that truth is Delhi’s biggest miscalculation.

Mamata’s Core Politics

What the BJP’s Delhi leadership repeatedly fails to grasp is that Mamata Banerjee is not a conventional opponent. Unlike leaders such as Rahul Gandhi, Akhilesh Yadav or Tejashwi Yadav, she is not a product of dynasty politics but of street mobilisation. Her political instincts were shaped in agitations, not drawing rooms and when the fight shifts to the streets, she is at her most formidable.

By provoking controversies over the SIR process, the Bengali language, and cultural icons, the BJP has unwittingly handed Mamata the perfect political turf.

These issues energise her core strengths: emotive politics, direct confrontation, and Bengali subnational pride. Every time the BJP appears to undermine Bengali identity, Mamata reclaims the narrative as the guardian of Bengal’s culture.

This serves another strategic purpose. By dominating the emotional discourse, she has successfully shifted public attention, and even the BJP’s focus, away from Bengal’s pressing concerns like unemployment, poverty, corruption, and governance failures. In this battlefield, she decides the terms, and the BJP keeps falling into the trap.

(Sayantan Ghosh teaches journalism at St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Kolkata, and is the author of The Aam Aadmi Party: The Untold Story of a Political Uprising and Its Undoing. He is on X as @sayantan_gh.This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)