Indians are finally waking up to Turkiye's unfriendly actions as far as India goes. I write finally because since (at least) 2019, Turkiye has been on an offensive against India.

Ever since Prime Minister Narendra Modi did away with Article 370—effectively ending the special status previously granted to Jammu and Kashmir—and bifurcated the state, Turkiye President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had been internationalising the Kashmir issue. He had even taken the issue to the United Nations—and has continued to do for a few years successively thereafter.

This was not all. As is the case with other Islamist groups like Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood, Turkiye also began hosting Kashmir separatists on its soil.

The Turkish media, too, had then too taken on itself the mission of becoming a voice for Kashmiri separatists.

It enabled Kashmir-related events on its territory. So much did it roil India that, following the Turkish invasion of Northern Syria in 2019, the Ministry of External Affairs had issued an advisory for Indian citizens against planning travel to Turkiye.

Of course, as a democracy an advisory was the maximum that the government could do—unlike Russia, which had stopped all travel to Turkiye when the latter shot down a Russian civilian aircraft in 2015.

Here, it is interesting to note that just a few days before the Pahalgam terror attack, TRT World (the Turkish channel's X account has now been blocked) had broadcast an interview with a Kashmiri separatist who had deplored the situation in Kashmir, describing Hindutvas as "worse than Zionists".

Also interesting is the fact that Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif was in Ankara when the massacre in Pahalgam happened.

Turkiye's Support For Pakistan

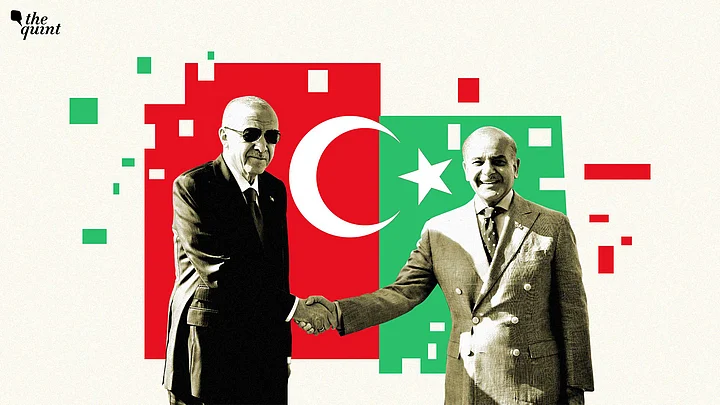

When Operation Sindoor began, it wasn't surprising to Turkiye observers that the country would come out so stridently in favour of Pakistan—and against India.

Turkish President Erdogan spoke with Shehbaz Sharif to convey his solidarity and support for Pakistan's "calm and restrained policies". On the other hand, its Ministry of Foreign Affairs said India's actions "raised the risk of an all-out war". Turkiye condemned such provocative steps, as well as attacks targeting civilians and civilian infrastructure, calling for de-escalation and an investigation into the Pahalgam attack.

As a ceasefire was achieved between India and Pakistan, Turkish media hailed "Pakistan's victory"—and Erdogan once again reiterated his support for Pakistan.

Turkish-made drones were used, and there is now increasing suspicion that some were delivered after the Pahalgam attack took place, as per flight tracking data. A Turkish Ada-class anti-submarine corvette was also docked at the Karachi Port on 2 May, and, according to sources in Azerbaijan—a close partner of both Turkiye and Pakistan—with Turkish military counselors in Pakistan.

No doubt the coming days will shed more light on Turkiye's role in the conflict. As far as political support goes, Turkiye has not shied away with it.

Why Turkiye Stands to Benefit

Turkiye's support of Pakistan is usually attributed to the religious linkages between the two. Indeed, Islam provides the ideological underpinning for the partnership. But it is equally driven by hard-nosed mercantile calculation—just as Turkiye's partnerships with other countries.

Take, for instance, the conflict in Gaza. President Erdogan has never failed to remember Gaza in almost every public pronouncement.

Turkiye shields Hamas members on its territory. Yet, it has not taken any serious step regarding trade with Israel as that would hurt Turkish interests.

With Pakistan, as well, Turkiye stands to benefit in a number of ways.

Both Pakistan and Turkiye are bonded by a common nostalgia for empire—Pakistan for the Muslim rule on the Indian subcontinent and Turkey for the Ottoman Empire. Both see themselves as inheritors of these legacies. The Pakistani state sees itself as the successor to the millennia-old Muslim rule in the Indian subcontinent, especially the Mughal empire, something that has shaped the country’s approach to security and its military.

After decolonisation, both Turkiye and Pakistan became US allies, and partnerships were formed with their inclusion in organisations like the Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO), a Cold War military alliance that laid the foundation for future cooperation.

Pakistan currently is a close defence partner and market for Turkish arms—from corvettes to drones. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), which conducts research on global security, arms trade, and military expenditures, Turkiye is Pakistan's second largest arms provider.

In 2018, Turkey’s STM Defence Technologies struck a $1 billion deal for four corvettes of a new class for the Pakistan Navy. The two sides regularly conduct joint military drills.

Pakistan’s National Aerospace Science and Technology Park (NASTP) have entered into an agreement with Turkish drone manufacturer Baykar for research and development. According to reports, Turkiye supplies Pakistan with F16 fighting falcon jets.

The cooperation is extensive.

Enter Azerbaijan

In this context, it is important to recall the 2020 war between South Caucasian rivals, Armenia and Azerbaijan, over the contested territory of Karabakh.

Thanks to extensive Turkish military help, after two decades of defeat, Azerbaijan could wrest control over the territory from Armenia. This victory has imbued a new belligerence and optimism in both Turkiye and Pakistan, close allies of Azerbaijan, over Northern Cyprus and Kashmir.

Turkish arms were a gamechanger in the war. This is a factor that strategists should not overlook.

For Turkiye, whose economy has been in duress for a long time now, its NATO-fired defence industry is its most lucrative revenue earner. From Central Asia to Somalia, Turkish arms are in demand. Pakistan is, thus, a lucrative source of income for Turkiye.

In many ways, like Pakistan, Turkiye also performs the services of a rentier state with its large, professional military, for rich patron states like Qatar. The militaries of both Turkiye and Pakistan can synergise, if needed, in any theatre of war.

Pakistan also provides Turkiye with the nuclear umbrella, as the only nuclear-armed Muslim country.

Political Dependency

Next is the political support that Pakistan and Turkiye can provide each other. In the United Nations, it translates into a vote. Turkiye sees a parallel on its claims on Northern Cyprus with those of Pakistan on Kashmir. In a move that mirrors Pakistan’s invasion of Kashmir in 1947, Turkiye invaded Cyprus in 1974.

It has since been insisting on the country’s partition to carve out a separate Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Right now, Turkiye is the only country that recognises the TRNC.

Following from the above is Turkiye's attempts to regain the power and pelf of its Ottoman ancestors. They were the last official Caliphate in the world, with Muslim nations, far and wide, acknowledging the Ottoman Sultan as their spiritual head.

Erdogan's Islamist-oriented Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi) has been using both its soft and hard power in its foreign policy to spearhead an alternative organisation to the Saudi Arabia-aligned Organisation of Islamic Conference, which is seen to be a paper tiger regarding Muslim affairs.

This has put Turkiye at loggerheads with Saudi Arabia and its other Arab allies from time to time. What should be remembered is that the demographic centre of the Muslim world has long shifted from the Arab World to South Asia. To that end, it has been making rapid inroads into South and Southeast Asia.

While Turkiye has a great following in India, it is the officially Muslim countries of Pakistan and Bangladesh whose populations and armies can be used in the service of Turkiye if necessary.

Finally, for Turkiye, as also for many countries in the Eurasian landmass, Pakistan also offers the shortest route to the sea, and thereby much needed shorter trade routes to South, Southeast, and West Asia. Turkiye does not have direct land access to Pakistan but it is definitely trying to establish one. This would equally be beneficial to Pakistan for its trade with Europe and for revenues earned through transit trade.

(The author is an award-winning journalist specialising on Eurasian affairs. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)