I am not a legal scholar. So, I cannot make arguments powered by pristine jurisprudence. But I am a first-generation entrepreneur and editor who’s had several face-offs with various laws — commercial, contractual, taxation, and free speech — either as a plaintiff or defendant. What I am about to write is inspired by my real-world experience and learning.

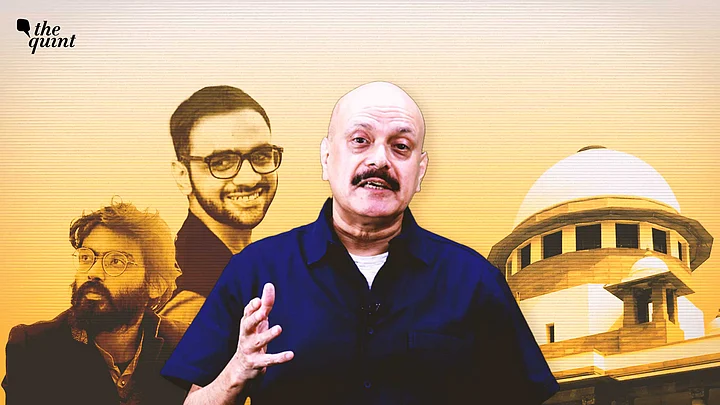

As with hundreds of experts, I too, was taken aback at the recent Supreme Court judgment denying bail to Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam. It’s a fairly settled proposition that bail orders should not cogitate on the evidence or merits of a case, ie bail should be governed by the imperative to guarantee the personal liberty of an accused who is presumed to be innocent until he is convicted.

Unless a person is a proclaimed offender with a track record of violence, intimidation of witnesses, and a demonstrated tendency to break jails or flee from justice, bail should be granted, almost as a default outcome. But the Supreme Court took off on an entirely new trajectory. It created a “hierarchy of actions” allegedly done by Khalid and Imam that somehow contaminated their presumption of innocence. Although all seven accused were charged under the same FIR, the court parsed them into two distinct categories. Five were thought to have committed a “lesser crime” and given bail, while Khalid and Imam were pronounced as potential kingpins in a “hierarchy” of the accused.

I was struck by how two honourable judges had dramatically expanded the scope of the bail law, much beyond the legislative intent of the lawmakers. Now the police can simply allege — not prove — by producing some “evidence” — which has not been cross-examined or challenged by the accused — to allege that “he or she was the ringleader”. Bingo! These allegations become sufficient grounds to deny bail to the purported kingpin, even as the FIR makes the same case against a group of accused people which is set free.

What an extraordinary expansion of the law by a judicial fiat, without going through the rigours of a legislative amendment! It’s a truism that the Supreme Court is the final authority to adjudicate on whether a law is constitutional, or whether it should be restricted or “read down” to align it with the sacred document. But here, the Court was “reading up” the statute, making it more expansive, pushing it into new, untrammelled, and unintended directions. And then I realised a disturbing truth — this was not an isolated order, but one of a series of recent judgments.

The Perverse Impact of the AGR Judgment

Six years back, the Supreme Court had shocked the corporate world with its adjusted gross revenue (AGR) order against telcos. India privatised telecoms in the 1990s, and the Operating License gave a clear, original definition of AGR: it would be the gross revenue of a telecom service provider, but would exclude specified items like interconnection charges, sale of handsets, and revenues from non-telecom operations such as income from land or property rentals, interest, dividend, and other non-core activities. This definition appealed to reason.

But in 2019, the Supreme Court created an entirely new model. It expanded the definition of AGR to include all collateral and non-core revenues like rentals and income from investments! The Court ignored the “letter” of the License and chose to articulate the silent “intent” of the law, which was to levy the fee on every activity “enabled” by using the telecom spectrum sold by the government. With a fierce stroke of the judicial pen, India’s telecom sector was burdened with over one lakh crore rupees of un-provisioned past liabilities, virtually killing a few operators.

The impact on balance sheets was bizarre. If you owned an office tower, you were penalised for earning rentals; against this, if you rented your office from a third party, you got off scot-free! If you were highly profitable, and invested your surplus in growth assets, you were penalised; instead, if you distributed all your profits as dividends, adversely affecting your ability to reinvest, you were rewarded!! It was perverse.

PMLA’s Lethal And/Or Switch

Another “celebrated” example is the humongous-ly widened ambit of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA). When promulgated in 2002, the PMLA was confined to egregious crimes like drug trafficking, terrorism and terror financing, narcotics, arms trafficking, and fraud. Via a couple of subsequent amendments, corruption and bribery, benami transactions, tax evasion, and laundering through shell companies and fictitious accounts were added as “scheduled crimes”. But the critical definition of money laundering remained unchanged:

“Whoever directly or indirectly attempts to indulge or knowingly assists or is a party to any process or activity connected with the proceeds of crime, including its concealment, possession, acquisition or use

AND (OR)

projecting or claiming it as untainted property shall be guilty of the offense of money laundering.”

In July 2022, the Supreme Court changed the letter of the law, as I’ve shown above in bold, capitalised, and underlined words. The original clause was AND. But the court specifically said it should be read as OR. That opened the sluice gates.

Let me explain with a simple example. Mr A and Mr B commit two separate robberies. Mr A simply keeps the cash in his garage and goes to sleep. But Mr B contacts a hawala operator and tries to insert the cash into his shell company as an “investment”. What has Mr B done? He has committed a crime AND tried to project the tainted money as clean. That’s the classic definition of “money laundering”.

But Mr A has done nothing of the sort. In the earlier law, where “and” was used, and both conditions had to be satisfied, Mr B was a money launderer, while Mr A was just a plain robber. Now, after the Court said read “and” as “or”, ie only one condition needs to be met, poor Mr A, just a simple, sleepy robber, has also become a dangerous money launderer!

A seemingly innocent switch from AND to OR has created the most dramatic expansion of PMLA, much beyond the original legislative intent!

I will end with how I began. I am not a legal scholar. I can only describe these judgments in layman terms. But here’s my question to legal pundits: is it correct for the Supreme Court to “read up” the statute? Is the Court exceeding its brief? Should the rewriting of a law not be left to Parliament?