Observing some trends in Indian politics these days, I am wondering if I am tracking national affairs or watching a family drama in a TV serial. But then, this is India, where power families are common – in business, politics, show businessa, and therefore, in soap operas too.

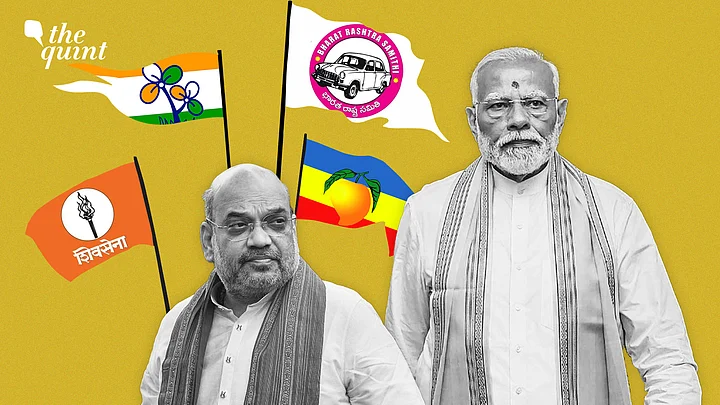

Over the past few months, there have been strong divides and simmering conflicts or family rifts in personality-driven parties and regional outfits including the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) in Uttar Pradesh, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) in Bihar, the Trinamool Congress (TMC) in West Bengal and the Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS) in Telangana.

The father-son clash in Tamil Nadu’s Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK) towers above them all.

Party founder S Ramadoss and his son Anbumani have been installing and/or expelling office-bearers and washing their dirty linen in full public view ahead of crucial assembly elections in the state due next year.

Things came to a head this week with a meeting convened by the father without the son, who happens to be the working president of the outfit. The party is on the verge of a likely split.

Degrees vary and styles differ, but the conflicts across the regional outfits are real.

Lovers' Tiffs and Family Dramas

Indian politics often sees personality clashes that look like lovers’ tiffs in which making up for mutual gains after some sulking or splitting is quite common. The rapprochement between cousins Uddhav and Raj Thackeray involving the UBT group of the Shiv Sena and its long-lost breakaway Maharashtra Navnirman Sena headed by Raj is a case in point.

The two jointly addressed a rally together but Raj’s MNS, accused of thuggery in asserting Marathi pride over Gujarati inhabitants of the state, is an ally for Uddhav thanks to his fallout with the BJP that has politically muscled its way to rule Maharashtra.

Adversity does make for strange bedfellows, but then, sibling and cousin rivalries in India are as old as the Mahabharata.

In Bihar’s RJD, Lalu Prasad Yadav’s son Tej Pratap has been expelled from the party in favour of his younger sibling Tejashwi, though the elder brother is a lightweight whose exit is of little consequence to the party.

Female siblings, once seen as showpieces in politics, are now emerging as leaders in their own right.

YS Sharmila, sister of defeated Andhra Pradesh chief minister YS Jagan Mohan Reddy of the Yuvajana Sramika Rythu (YSR) Congress, is now a leader of the Indian National Congress, while Kalvakuntla.

Kavitha, daughter of BRS founder K Chandrashekar Rao, has all but openly said she won’t be playing ball under brother KT Rama Rao. In PMK, the 86-year-old Ramadoss is propping up his daughter Kanthimathi to counter his 56-year-old son.

In TMC, West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee’s nephew and party general secretary Abhishek is back in the reckoning after rumours of a rift, while in UP, Mayawati installed her nephew Akash Anand back in the party after expelling him following a public apology. Her condition is that his father-in-law will not be allowed to influence him. That is real soap opera stuff.

Not all parties enjoy similar fates.

The Urgent Need for 'Professionalisation'

All this has ominous implications for national politics. I see Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as a major gainer, and is also accused in some cases, as in the case of the PMK and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) of engineering factional divides in regional parties for its own gains.

It has already split the Shiv Sena with the main group hijacked as a ruling ally in Maharashtra and left its former leader licking his political wounds.

Looking beyond this, I find that in politics, as in business, there is an increasing need for “professionalisation”. Over a period time, loyalties based on caste, community, old relationships, and kinship habits must give way to principles and processes to engage increasingly conscious young voters. If not, such parties face an existential threat.

Just as managements of companies need to keep customers, employees, and shareholders happy, political parties need to keep voters, office-bearers and those who fund it reasonably satisfied.

This puts pressure on them to balance intra-family rivalries with aspirations of grassroots workers and meritorious members.

Reading between the lines of the conflicts, what seems likely is that while family heirs are often anointed as preferred candidates, it involves either personality clashes within the extended families or concerns over how to keep party cadres motivated. Much like IT giant Infosys, in which founder N.R. Narayana Murthy faced unrest among senior professional executives when he temporarily brought in his son Rohan into the corporate office, party workers seeking posts and other spoils of power do not like unacceptable interventions that erode their prospects or their ability to deliver results.

Politics is increasingly competitive, and both ideology and kinship seem to be mattering less and less.

Voters no longer necessarily vote for a leader or party just because they respect its founder/leader, or form part of a certain caste or community. Party cadres often echo that behaviour. Old leaders have to build their support base both with voters and party workers by showing how they can deliver – and this is what has led to professional election “service providers” like Prashant Kishor, who is now steering his own political party in Bihar after spending more than a decade as an “outsourcing” entrepreneur in the vote-catching business.

Kishor, who is currently advising Tamil actor Vijay's new outfit, the Tamizhaga Vettri Kazhagam (TVK), now has me-too rivals who try to manage election outcomes using data, staff and programmes for various parties. But there is a limit to the outsourcing model in politics, because cadres and leaders inside need to have a grip and have to be seen exercising the grip.

Political parties have also begun to resemble broad-based consumer goods companies like Hindustan Lever and its rivals like Marico, Godrej Consumer Brands, or Procter & Gamble. They offer similar products with minor variations in positioning and packaging. In politics, the equivalents of soaps and toothpastes are welfare schemes for women, farmers, youths and caste groups.

Party workers nurture local constituencies much like sales managers of corporate giants and switch jobs - as ambitious employees often do.

In such a context, family-oriented parties, like family-run businesses, have to usher in some kind of meritocracy and let smarter workers hold key offices or steer election campaigns.

Regional parties are becoming takeover targets for national giants. If they do not play ball in coalitions, their cadres are raided or their parties split into factions.

The BJP can use its levers of power (including budget allocations and law enforcement agencies) to reward willing hands or twist arms where necessary. It can, as it has already done, bring in new elements into the party, and use its mighty organisational power to energise and deploy competent lateral entrants. However, it also has to contend with old party loyalists and its ideological parent, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in mind.

Here is an interesting twist. I do believe the demographic transition in India is of such a humongous proportion that you have literally thousands of ambitious newbies entering politics, resembling corporate employees becoming startup entrepreneurs.

Time to Professionalise or Perish

But this maxim applies more to regional parties that face imminent threats from the BJP. The Congress, though it is a national party, faces “regionalisation” if it does not watch out.

The BJP exists to show the might of discipline and focus. While its rivals may disagree on its ideas and programmes, they have to take a leaf or two out of its playbook. The only BJP rival that matches its approach reasonably is the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, though their ideological differences are huge.

What we are about to witness over the next two years is a period in which the young and the restless have to be wooed, empowered, and accommodated, be they voters or party activists.

(Madhavan Narayanan is a senior journalist and commentator who has worked for Reuters, Economic Times, Business Standard, and Hindustan Times. He can be reached on Twitter @madversity. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)