According to PRS Legislative Research's report and analysis, the Winter Parliamentary Session of 2024 – held from 25 November to 20 December – functioned for 52 percent of its scheduled time for the Lok Sabha, while the Rajya Sabha functioned for 39 percent.

Out of the total time spent, only 37 percent of the Lok Sabha session time went towards legislative activity, while 22 percent of the Rajya Sabha session time went towards legislative business.

Even during this short period of legislative activity, only four bills were introduced, with one passed during the session (excluding the appropriations and finance bills).

A notice to move a motion for removal of Rajya Sabha Chairman and Vice President Jagdeep Dhankar was submitted in this session on 10 December. It was the first such motion against the Vice President. The notice, however, was rejected by the deputy chairman of the Rajya Sabha on “procedural grounds”.

Historical Context

It's unfair to relate the governing dynamics of parliamentary effectiveness with its functioning level alone. Still, last year, for the 2023 Winter Session, the 17th Lok Sabha had functioned for 74 percent of its scheduled time and the Rajya Sabha for 81 percent.

This winter, for the 18th Lok Sabha, even that active functional time for the Parliament to convene and discuss legislative business dropped drastically for each House.

This has clearly impacted the ability of both Houses to discuss the order of legislative business, including robust deliberations on tabled bills.

Earlier parliamentary sessions under the Narendra Modi government saw higher legislative activity – but amidst a rail-roading of bills being introduced and passed. 56 percent of bills introduced were passed till 2023 Monsoon Session – with little scrutiny – by both Houses (where a bill on an average was passed within eight days of introduction).

With the 2024 Lok Sabha polls decreasing the Bharatiya Janata Party's (BJP's) numbers in the Parliament, its ability to get bills passed or railroaded, especially those requiring two-third majority, remains weakened, like the One Nation One Election Bill (that was defeated this time in the ruling party’s failure to get the required parliamentary votes). There are also certain issues that still remain pending to be addressed from previous Lok Sabhas.

The 17th Lok Sabha did not elect a deputy speaker for its entire term, and since 2019, there has been no appointment made on the position. The 18th Lok Sabha, too, has not elected a deputy speaker (note how in 2023 the Supreme Court in response to a PIL on this issue had issued a notice to the Central government). The Constitution, in its 75th year (celebrated recently), requires the Lok Sabha to choose a speaker and a deputy speaker as soon as possible.

Regression in Parliamentary Discourse, Critique and Reflection

Previously, according to PRS Legislative, "the 17th Lok Sabha (till 2023) passed 22 bills (in Monsoon Session alone). Twenty of these bills were discussed for less than an hour before passing. Nine bills, including the IIM (Amendment) Bill, 2023 and the Inter-Services Organisation Bill, 2023, were passed within 20 minutes in the Lok Sabha."

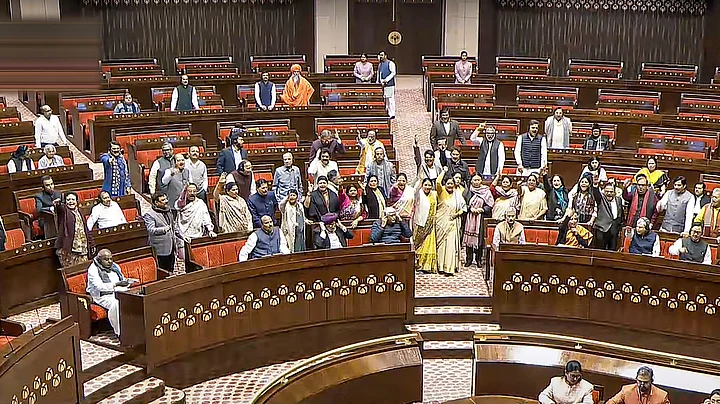

Waves of Parliamentary theatrics have defined the disjointed operative functionalities of the Indian democracy over the last decade. This Winter Session’s disruptions and inability to get business of the House(s) in order is a clear case in point.

For watchers and observers of each parliamentary session’s proceedings, repetitive acts of adjournments, a perpetuated ecosystem of chaos, red flags and protests (inside and outside the chambers of House) by the Opposition, accompanied by the bias and favouritism in attitudinal modulations of House speakers (against the Opposition party parliamentarians), have become a part of an unusual norm, catalysing a speedy passing of bills by the ruling executive, without critical discussion or appropriate reflection.

There is an insidious way in which the current regime has used the legislative and other institutionalised apparatus to also further its agenda of establish centralised, consolidated, and absolutist control.

The presence of legal voids (say from recent or previous SC judgments) amidst a weaker Opposition makes its path less embroiled with challenges. That’s even more troubling.

Last year’s parliamentary sessions, as an observer, saw three highlights, signaling a crisis (in transitioning permanence) of parliamentary and government accountability, an overcentralised executive action (under institutional capture), just in the way different bills were passed and issues in them were ignorantly dismissed.

Once the bill has become law, the Union government will get most of the powers to define and exercise the scope of its application and the substance of data protection regulations.

This is where Shakti Ki Gita – a rule by law for an absolutist governance regime (even if in power by an internalised coalition) – enables to use the instrument of law to play mischief, as and when it wants, with zero accountability for its actions.

While reflecting on the selective interpretation of events and the way the proceedings happened, as they transpired this session (as a pattern seen for some time now), one can only reminisce how in the current governmentality, there are elements similar to that of the British Raj that ruled India for over two centuries (first by the East India Company and then by the Queen’s rule), establishing an imperial umbrella – centralising, consolidating power via law, language, and knowledge.

A systematic capture of independent institutions, seen amidst a deep retrogression in democratic values, and constitutionally safeguarded separation of powers, one may only ascertain how the current state of polity in India closely resembles the lived experience of a colonial administration, consumed by its anxieties, insecurities, and controlling-nature to rule-govern and patronise at all costs sans accountability, or regard for constitutionalism.

(Deepanshu Mohan is a Professor of Economics, Dean, IDEAS, Office of Inter-Disciplinary Studies, and Director of Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES), OP Jindal Global University. He is a Visiting Professor at the London School of Economics, and a 2024 Fall Academic Visitor to the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford. This is an opinion article, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)