(Note: The byline has been withheld at the request of the author.)

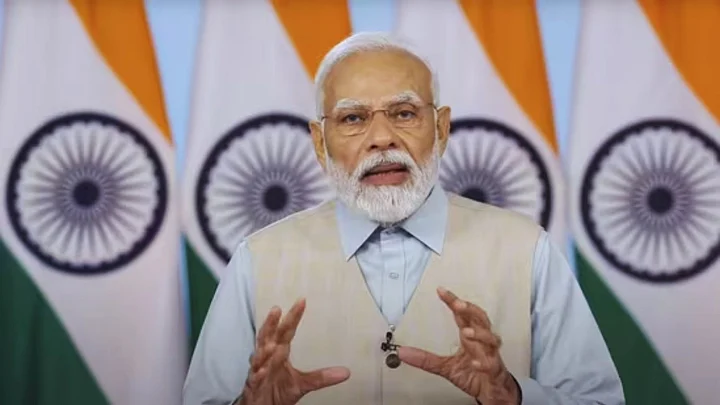

Over the last few years, one of the repeated aims of the Indian government under Prime Minister Modi has been to establish India as a vishwaguru or world teacher. This goal was amongst the many themes of India’s presidency of the G20 held in New Delhi in 2023. As I travelled across the country during this time, the impulse was obvious: a smiling and secure Modi was signalling India’s openness to foreign attention and interest.

With the growing multipolarity of the international world and the seeming payoffs of India’s liberalisation policy of the 90s, this has been a long-anticipated posture. The government’s position has consistently been that India is now prepared to catapult itself from being a regional leader to a key international player in cultural matters, diplomacy, trade, and manufacturing.

Part of this position includes attempts to isolate China from the Western world and present India as an alternative site for capital investment and human resources development. The Big Indian Bet balloons bit by bit each day.

Western news publications write incessantly of India’s economic potential through the growing purchasing power of its elite— there are now over 800,000 dollar millionaires, its homegrown tech hub in Bangalore, and a new destination for foreign investment in Asia. Modi and his government have wholeheartedly embraced such coverage. Frankly, who wouldn’t? Yet, in my mind, this also raises the question of what animates the substantive core of this form of leadership.

Thus far, Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) vision has demonstrated that their interpretation of being a ‘world teacher’ is marrying participation in global capitalist markets with a supposed indigenous “Indian” inflexion. A signal that India would not just be a global leader in the mould of other Western countries but something different. For Modi and the BJP, this means the crafting of India as a civilisation-state with not only accessible and fecund financial markets but also the gift of ‘Eastern’ insights and values.

But as has become evident over the last ten years, this sense of “Indian” values is wholly derived from their domestic attempts at shaping India into a Hindu nationalist state. Internally, this has meant abjuring secularism; condoning and promoting violence against Muslims; maintaining a heightened military occupation in Kashmir with elections taking place now after a decade; punishing critics of the government; and the list goes on.

Similarly, in a macabre twist, the government has also attempted to appropriate the narrative of decolonisation. The BJP seeks to “decolonise” India not through the questioning of existing imperial and neo-imperial power structures but through renaming ‘Islamic’ or ‘British’ sounding cities and towns with more “indigenous” Sanskritised names.

Decolonisation here means a reversion to an illusory Hindu Golden Age sans the British, sans Muslims, and sans modern, universalist political values. The domestic alarm bells have been tolling for years now but support for Hindutva has stayed high and stable with only minor ebbs and flows. To those of us who care, it is obvious that the moral core of such domestic leadership is hollow, and it seems the same can be said of its international equivalent. As scholar AG Noorani put it, promoting India as a vishwaguru simultaneously seeks to build global acceptance of Hindutva.

The overemphasised link between India as a state and Modi’s populist and Hindu nationalist values has come to eclipse a previous history of India as a geopolitical pioneer, one more attuned to deeper and less reactionary understandings of decolonisation.

India’s international priorities in the aftermath of Independence were animated by Third World solidarity: the Bandung Conference of 1955 which sought to forge Afro-Asian cooperation recognised the material risks of the exercise of newfound sovereign political power during the Cold War. More than twenty-five countries at Bandung discussed the importance of protecting sovereignty at a time of postcolonial poverty and vulnerability and maintaining neutrality in the face of imperial battles in the Global South; expressed scepticism of defence pacts such as NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) whose sphere of interest was ever-expanding; and emphasised independence for countries still under the yoke of colonialism.

After Bandung Indian state policy mirrored these principles in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) as a method by which to maintain political independence and neutrality against proxy wars being fought by imperial powers in the Global South. As a point of comparison, Pakistan’s post-independence constitutional failures can be understood as the pitfalls of over-dependence on imperial support, such as accepting large amounts of American aid which hamstrung political groups and promoted military rule.

As the Bandung-NAM world order ended because of reasons beyond its control, its legacy in India has remained thin. Today, it is a tragedy that India’s rich history as a leader and coordinator of Global South power and solidarity through the vehement rejection of apartheid in South Africa via diplomatic, commercial, cultural, and sports boycotts; condemnation of the war in Vietnam and recognition of the government in North Vietnam in 1972 (three years before the Fall of Saigon); and military support for the Bangladeshi War of Independence has been replaced by weak rhetorical gestures.

In the last year, the greatest test of political leadership and solidarity against Western imperialism emerged in the wake of the 7 October attacks in Israel. Devastating as they were, the subsequent bombing, destruction, pillaging, and starving of Palestinians in Gaza have no contemporary or recent equivalent. As has been argued innumerably before, Palestine is the most fundamental litmus test for analysing and opposing imperial rule in the 21st century. South Africa, with its own legacy of apartheid and colonial supremacy, rose to the occasion and charged Israel with genocide in a lucid and tempered case on behalf of the Global South.

The fact that India was not a co-signatory to the case and nor has it used other tools— arms embargoes, boycott, diplomatic dismissal— in its arsenal speaks to the shifts in the priorities of its political leadership. None of this is to say that Palestinian statehood was one of the primary international priorities of the Indian state— in fact, the normalisation of relations with Israel was undertaken by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in the 1980s. Yet the establishment of diplomatic relations with Israel is still distinct from the Modi-Bibi romance narrative crafted over the last few years, where India’s former Third Worldist concerns are a faint memory. Instead, it supplies Israel with weapons in its crusade of destruction.

Further illustrating this nihilist turn, over the last year, Indian foreign policy has been diminished to parroting the quite dead reality of a two-state solution; indicating support for a ceasefire yet using no diplomatic tools towards the same; abstaining in a United Nations General Assembly vote that Israel “end its unlawful presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory without delay and within the next 12 months”; and lastly, by materially supporting the Israeli state by sending at least 6000 construction workers to replace Palestinian workers whose permits the Israeli government suspended en masse after 7 October. This move was opposed by several different labour unions in India, who recognised that Indian labour was being conscripted to replace Palestinian labour and further exacerbate the separation of Palestinians from access to resources and their livelihoods.

That Indian foreign policy on this issue has been shorn of its internationalist and moral core is not a coincidence. The parallels between Hindutva and Zionism are apparent. Both are founded upon the self-conception of a civilisational state defined by the existence of a ‘privileged’ people and their exclusionary practices to the Other, ie, Arabs or Muslims. Both seek out vigilante violence as a form of cultural and social control: lynchings of Muslims are condoned by the BJP, while the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) protects settlers who attack and harass Palestinians in the West Bank.

Most recently, these xenophobic convergences between them culminated in separate ethnonationalist citizenship laws being promulgated in Israel (2018) and India (2019) which exclusively promote Jewish and Hindu citizenship and “return”. And lastly, some of the most unequivocal support for Israel’s campaign of annihilation in Gaza has come from Hindu nationalists who see Israel as a model of machismo and unrelenting supremacy worth replicating.

Since India has tasked itself with aspirations of global leadership while bearing in mind its history as a formerly colonised country then these actions point only to the opposite. The Western world has consistently shown its moral void and pure apathy towards Palestinians by supporting Israel unconditionally even as schools, hospitals and civilians are bombed daily. Now there is also the risk of an escalated war with Lebanon through unprovoked bombings of Beirut.

In the face of this, leadership informed by “decolonisation” and indigenous Indian insights are meaningless if they do not help stop genocide. Bandung and NAM have left us with a rich legacy of anti-imperial internationalism and if India still seeks to project itself as an alternative pole of authority, then this is the moment to demonstrate it: by boycotting and isolating Israel as it did with apartheid South Africa. Supporting Palestinians is our most crucial test not only because it would maintain historical consistency with the values of the Indian independence movement but also because it is the correct thing to do.

(The writer is currently a PhD student at Yale University. This is an opinion article and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)