During the Parliament's special discussion marking the 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram, two incidents highlighted a troubling gap in public knowledge about Bengal's profound contributions to India's freedom struggle and progressive thought.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi referred to Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, the song's author, as "Bankim da"—a colloquial Bengali term of affection akin to "elder brother," often shortened from "dada."

In Bengali cultural tradition, however, Chattopadhyay is reverently addressed as "Rishi Bankim," signifying his status as a sage-like figure whose works transcended mere literature to inspire a spiritual awakening.

This honorific parallels "Rishi Aurobindo" for Sri Aurobindo Ghosh, underscoring their roles as visionary thinkers rather than familiar elders.

Compounding this was a remark by Rajya Sabha MP Dinesh Sharma, who described the iconic freedom fighter Matangini Hazra as having raised the Vande Mataram slogan "despite being a Muslim."

Hazra, born in 1870 in a village near Tamluk in present-day West Bengal, was a devout Hindu widow from a poor peasant family. Known as "Gandhi buri" (old Gandhi woman) for her adherence to Gandhian principles, she led a procession during the Quit India Movement in 1942.

At 72, she marched toward the Tamluk police station, chanting Vande Mataram, and was shot dead while clutching the tricolour flag. Her martyrdom symbolised unyielding resistance, yet this factual error in the Parliament shows how little the country knew about her.

These gaffes are not isolated but symptomatic of a broader issue: the persistent lack of nuanced understanding of Bengal's pivotal role in shaping India's nationalist imagination and revolutionary zeal.

As politics grows polarised, attempts to invoke historical icons often reveal superficial engagement, distorting legacies forged in Bengal's intellectual and sacrificial crucible.

Polarisation and the Rush to Appropriate Bengal's Legacy

India stands at a crossroads where political polarisation has normalised divisive narratives. Since the late 1980s, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has dominated northern India's political landscape, rooted in Hindutva ideology. Now expanding southward and eastward into states like West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala—regions with robust cultural identities and minimal historical BJP presence—the party seeks cultural relevance by invoking local heroes.

In West Bengal, this manifests as efforts to claim figures from the Bengal Renaissance and the freedom movement. Yet, such appropriations often stumble over basic facts, alienating those familiar with the region's history.

The desperation stems from electoral imperatives: ahead of the Assembly polls, national symbols like Vande Mataram are weaponised, but without grounding in Bengal's context. This not only fails to build bridges but reinforces perceptions of external imposition, widening the chasm between northern-dominated narratives and southern/eastern regional pride.

The Errors Reveal Deeper Ignorance

The 2025 parliamentary discussion on Vande Mataram's anniversary devolved into blame-trading over its historical truncation, with truths obscured amid partisan accusations. Beyond the incidents involving Chattopadhyay and Hazra, similar errors abound.

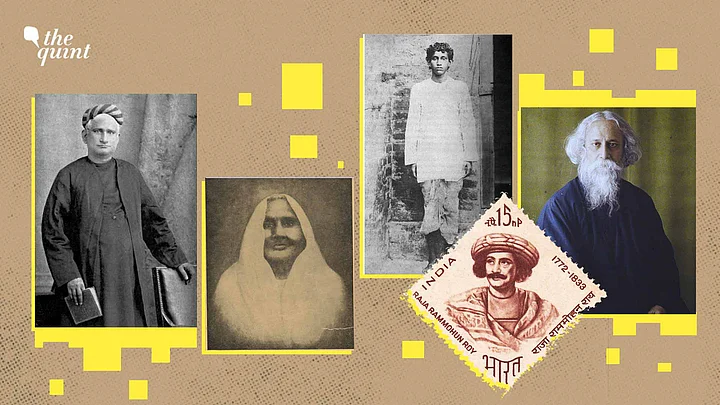

A Madhya Pradesh BJP minister recently labelled Raja Rammohan Roy, the Brahmo Samaj founder who abolished sati, a "British agent" facilitating conversions—ignoring his role as a moderniser challenging orthodoxy.

Earlier, an Assam BJP figure reportedly called Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose a "terrorist," overlooking Bose's leadership of the Indian National Army and global alliances against colonialism.

These are not mere slips; they reflect a reluctance to engage deeply with Bengal's history. Fact-checking, even via accessible tools, seems secondary to rhetorical point-scoring.

This is not exclusively a BJP issue. Across parties, Bengal's contributions are selectively highlighted or ignored for convenience. The core problem: political mileage trumps historical accuracy, whitewashing complexities and assigning blame without accountability.

Bengal's Indigenous Hindutva: Roots Unlinked to Organisational Forms

Undivided Bengal possessed a rich Hindu nationalist tradition that was historically and intellectually distinct from later pan-Indian organisational frameworks.

Shyama Prasad Mookerjee, a leading figure from Bengal and founder of the Jana Sangh (the BJP’s predecessor), did not seek to root either the RSS or the Jana Sangh within this indigenous Hindu nationalist legacy. Instead, his engagement remained primarily political—aimed at Hindu consolidation within constitutional and electoral arenas—without forging deep organisational or ideological alignment with the RSS’s cadre-based ethos or attempting to subsume Bengal’s past into Jana Sangh’s framework.

Bengal's Hindutva drew from cultural revival: The Hindu Mela, initiated in 1867, promoted indigenous crafts and pride predating widespread organisational Hindutva. Bhudev Mukhopadhyay's 1866 satirical work Unabimsa Purana first conceptualised the nation as "Adi Bharati," a maternal figure. Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay's Anandamath (1882) vividly portrayed India as Bharat Mata, invoking Durga and Lakshmi to fuse anti-colonial struggle with Hindu imagery.

Abanindranath Tagore's 1905 painting 'Bharat Mata'—depicting a serene, four-armed goddess dispensing knowledge, food, clothing, and spiritual solace—became the iconic visualisation, initially titled 'Banga Mata' (Mother Bengal). Rarely acknowledged in contemporary invocations, this lineage underscores Bengal's organic nationalism.

The sole, and highly limited, point of contact often cited is that RSS founder Keshav Baliram Hedgewar briefly came into contact with Bengal’s Anushilan Samiti during his medical studies in Calcutta. This short-lived personal association neither translated into organisational continuity nor established any lasting connection between the RSS and Bengal’s nationalist movement, which evolved along its own distinct and intellectually autonomous trajectory.

A Shared Failure: Distortions Beyond One Party

Ignorance of Bengal's history transcends party lines. The 2019 film Kesari referenced revolutionary Khudiram Bose—who, at 18, attempted to assassinate a British magistrate in the 1908 Muzaffarpur conspiracy and was hanged smiling, clutching the Bhagavad Gita—as "Khudiram Singh," implying Punjabi origins.

"Khudiram," meaning "Krishna in childhood form," is quintessentially Bengali; no Punjabi naming tradition aligns. This distortion erased Bose's Bengali identity. Recent films on Bengal's Partition selectively portray violence, lacking contextual depth.

Even the Congress, deeply intertwined with Bengal—through Netaji Bose, Rabindranath Tagore, and others—has historically centred narratives on Nehru-Gandhi contributions, marginalising regional sacrifices.

India's diversity demands acknowledging each state's profound histories. Political gain through uninformed appropriation reveals regressive tendencies, eroding collective memory.

Bengal's socio-political and cultural history has long invited robust ideological criticism, often from the Left, which dominated intellectual discourse in the state for decades. The undivided Communist Party of India (CPI), aligning with the Comintern's anti-fascist stance during World War II, vehemently opposed Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose's alliances with Axis powers.

Bose's strategy of seeking military aid from Germany and Japan to expel British colonialism was deemed collaboration with fascism; CPI publications caricatured him as "Tojo's dog" (referring to Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo) and a "running dog of imperialism."

This was not mere slander but rooted in Marxist internationalism, prioritising the global fight against fascism over immediate anti-colonial armed struggle. Similarly, Rabindranath Tagore faced Marxist scrutiny for his perceived bourgeois humanism, universalism, and critique of narrow nationalism. Early Left critics dismissed him as an "ivory tower" poet detached from class struggle, overly celebratory of joy amid exploitation, or insufficiently revolutionary. His emphasis on individual freedom and spiritual unity clashed with proletarian dictatorship ideals.

Yet, these were ideologically grounded critiques—debatable, often harsh, but informed by theoretical frameworks. Over time, the Left corrected its stance: CPI(M) leaders like Jyoti Basu and Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee publicly acknowledged "mistakes" in assessing both Netaji and Tagore, recognising Bose's patriotism and Tagore's profound social insights.

The Left rarely championed Bengal's indigenous Hindutva-nationalist lineage but engaged with it critically, not through ignorance. In contrast, recent appropriations—particularly by the BJP—suffer from superficiality and factual errors, as seen in parliamentary gaffes over Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay and Matangini Hazra.

While the BJP pursues grassroots expansion in Bengal, this pattern of uninformed invocation breeds disdain among Bengalis attuned to their history. It reinforces perceptions of cultural insensitivity, allowing figures like Mamata Banerjee to frame opponents as "anti-Bengali.

(Sayantan Ghosh teaches journalism at St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Kolkata, and is the author of The Aam Aadmi Party: The Untold Story of a Political Uprising and Its Undoing. He is on X as @sayantan_gh. This is an opinion piece and views expressed are the author's own. The Quint does not endorse nor is responsible for them)