The ‘sensational’ Hema Updhyaya-Harish Bhambani double-murder has once again focussed attention on the police’s harmful practice of staging media trials.

On 14 December, the Uttar Pradesh Police’s Special Task Force paraded Vidyadhar Rajbhar, a suspect before the media. Flanked by policemen, Rajbhar ‘confessed’ to the media his modus operandi and motives for the killings.

The actions of the police reveal their tendency to create a case and have it judged even before it reaches the court. This, according to the Constitution and long-settled principles of criminal jurisprudence is a violation of the fundamental right to a fair trial.

Sadly, the UP cops aren’t alone — the Delhi Police’s Special Cell is probably the most notorious in this department, and police forces in other states have also begun emulating this practice. And to date, the courts have not been able to do much to rein them in.

Questioning the Police’s Actions

In the Mumbai double murder case, the police are yet to present Rajbhar before a Magistrate so that his statement can be recorded. The investigation has barely started, and the case is only three days old. All the police have till now is a confession statement, which cannot be admitted as evidence in court.

Then, why is the police giving out details to the media as if it was presenting a chargesheet in court? And why the tearing hurry to reveal all to the public, for both consumption and speculation? Especially when, in many cases, both the police and the prosecution do their best to delay presenting the chargesheet to keep some people under prolonged detention.

How the Police Manufactures Cases in the Media

Kamini Jaiswal, senior Supreme Court lawyer, says,

It is essentially to build a case out of thin air in order to whip up public frenzy and prejudice against the accused.

Jaiswal, who has won many acquittals in high profile terror cases, cites the example of SAR Geelani, the Delhi University professor charged with participating in the conspiracy behind the 2001 Parliament attack case.

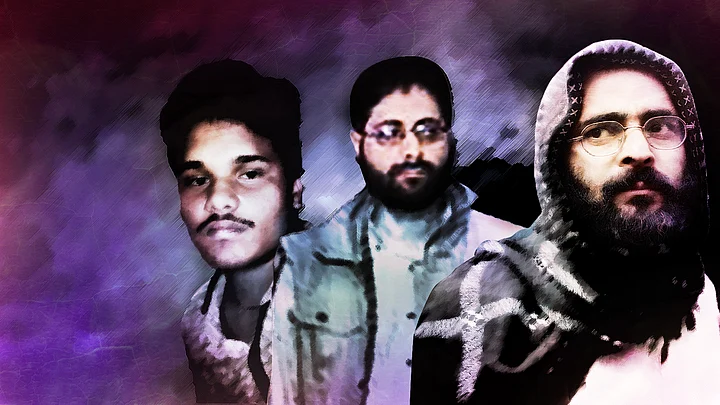

A couple of days after arresting him, the Delhi Police’s Special Cell held a press conference, where in the blazing light of flashbulbs, Geelani was made to read out a statement, confessing to all the charges against him. After a tough legal battle, Geelani won his freedom in the Supreme Court, where the prosecution’s case against him collapsed. But, says Jaiswal, till to this day, that one press conference hangs like an albatross round his neck, and he is still suspected by the public and police alike.

The above video shows Delhi Police Special Cell personnel displayed Geelani as a trophy, compelled him to implicate himself.

In 2012, Syed Mohammad Kazmi, a Delhi journalist, was arrested and charged with plotting a bomb blast on the car of an Israeli diplomat. The Special Cell lost no time in picking up Kazmi, parading him before the media, and pronouncing him guilty.

After spending seven months in jail, Kazmi got bail from the Supreme Court, and his case is still pending. Mehmood Pracha, Kazmi’s lawyer, detailed how the police told two versions — one before the media, and one before the court.

In the version fed to the media, the police even went so far as to create identities of people which they did not even attempt to prove in court.

Media Trials Also Hurt Investigations

In 2008, a Delhi High Court Bench headed by Justice AP Shah slammed the Special Cell for its practice of parading arrested suspects before the media and making them read out confession statements.

The police, in turn, asked the court itself to frame suitable guidelines. The court rightly declined, because the onus of not violating a person’s fair trial rights should be on the State and its agents, not the judiciary.

The court also made a significant observation — that releasing a torrent of information to the media before it can build a watertight case boomerangs against the police, by hurting investigations.

Can the Courts Hold the Police to Account?

Recently, the Mumbai Police has informed the Bombay High Court that it has come out with a 2014 Circular which lays down a strict protocol for releasing information to the media. However, its latest actions prove that it was speaking in a forked tongue.

Could the courts be relied upon to reform the police? It is clear by now that the police trigger off media trials in order to influence judicial outcomes. Indeed, there is evidence of judges being swayed by the gush of media coverage — the Law Commission of India said so in 2006, and in May this year, even a Delhi High Court Bench admitted as much.

Every criminal trial must be judged according to law, not in accordance with public perceptions and personal prejudices. Why should the police get away with tramping upon this principle?