Tamil Nadu is yet again in protest mode after protest broke out over Jallikattu in January 2017 – this time over the Centre’s delay in forming the Cauvery Management Board for the appropriate distribution of Cauvery water between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

From Rajinikanth calling for a ban on the IPL, to the entire Cabinet of Ministers threatening to quit, here’s why the Cauvery issue is, and has always been, a live wire.

Will Tamil Nadu and Karnataka’s Fight Over Cauvery Ever End?

1. What is the ‘Cauvery Issue’?

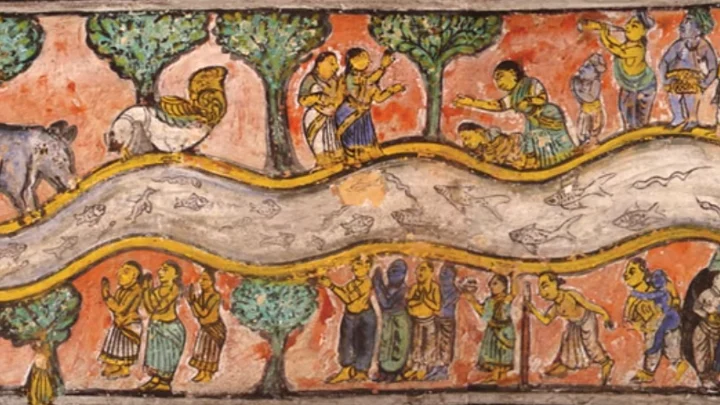

The Cauvery is a perennial river that originates in Karnataka, and flows through Tamil Nadu into Puducherry. It merges with the Bay of Bengal. It is Tamil Nadu's only perennial river and currently the source of over 70 percent of canal irrigation that supplies water to the state's agricultural lands. A number of districts in central and western Tamil Nadu, as well as parts of Madurai and Ramanathapuram, have come to depend on Cauvery for drinking water as well.

Equitable and timely sharing of water by Karnataka to Tamil Nadu, therefore, is vital to both agriculture and drinking water needs of TN.

For decades, the two states have fought over the timeliness, frequency, and quantity of water that each is entitled to. This issue has also been an electoral issue, and a means of polarising the two states against each other.

On 16 February 2018, a special bench of Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra delivered the verdict on the issue, largely upholding the water-sharing arrangements finalised by the Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal (CWDT) on 5 February 2007.

An important change from the CWDT arrangement was that the Supreme Court awarded an additional 14.75 tmcft (thousand million cubic feet) to Karnataka, keeping in mind the growing drinking water needs of Bengaluru, which it said had attained ‘global city’ status.

Tamil Nadu's share was therefore brought down to 177.25 tmcft from the earlier 192 tmcft. The court further directed Tamil Nadu to tap into 10 tmcft of ground water, roughly half of the existing stock of an 'empirical' 20 tmcft.The CWDT had not taken the ground water reserves into account while awarding the water sharing arrangement. The Supreme Court also directed the Centre to formulate a 'scheme' to implement the verdict.

Herein lies the controversy.Expand2. Why is Supreme Court’s 16 Feb Verdict Problematic?

The issue lies in the differing interpretations of the verdict by Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, specifically with regards to the formulation of a 'scheme' for 'implementation of the verdict.’

According to Tamil Nadu media, government, and consequently the electorate, the formation of the scheme includes the formation of the Cauvery Management Board (CMB) and the Cauvery Water Regulations Committee. The CMB would be an autonomous body that would ensure water distribution as per the verdict, and would function independent of Karnataka or Tamil Nadu but include stakeholders from both states.

But Karnataka's Water Resources Minister MB Patil stated clearly that the SC order does not include the constituting of a 'board.’ According the minister, the state is open to the formulation of a scheme to implement the verdict.

The formation of the CMB would wrest control of Cauvery's waters out of Karnataka's hands.

The government at the Centre could agree to the formation of the CMB as part of formulation of the 'scheme' to implement the verdict, owing to pressure from Tamil Nadu. If this happens, it is possible that Karnataka might protest.

Tamil Nadu wants a board which will ensure timely release of water as per the 2007 tribunal’s final order. This has been Tamil Nadu’s biggest grouse against Karnataka.

It was to address this that in May 2012, the then chief minister of TN J Jayalalithaa requested the then prime minister Manmohan Singh to convene a meeting of the Cauvery River Authority immediately. The Cauvery River Authority, under the prime minister, was a monitoring body that was to ensure the implementation of the 2007 tribunal.

Jayalalithaa’s complaint against Karnataka was that the state had been unjustly utilising the water for summer irrigation (almost 41 tmcf), thereby severely depleting storage during summer; also that water was released only during the rainy season when the reservoirs start to have surplus.For Tamil Nadu, the formation of the CMB is mandatory in order to stop Karnataka's discrepancies in sharing water, which have historic precedence.

Expand3. When Did it All Begin?

An agreement between the then Madras State (Tamil Nadu) and the princely State of Mysore (Karnataka) was signed in 1924 and came to an end In 1974. This agreement was actually a continuation of an earlier agreement signed in 1892.

From 1970 onwards, Tamil Nadu (then Madras State) had been asking the Supreme Court to set up a system for distribution of Cauvery water equitably.

Finally in 1990, for the first time, the Supreme Court directed the Centre to constitute a Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal (CWDT). While the CWDT went about its fact-finding mission, Tamil Nadu sought interim relief.

The CWDT, thanks to the intervention of the Supreme Court, ordered Karnataka to release 205 tmcft, which Karnataka refused to oblige to.

In 1993, Tamil Nadu CM Jayalalithaa went on a sudden fast at the MGR memorial in Chennai, demanding the state’s share of water as per the interim order.

After 80 hours, VC Shukla, the Water Resources Minister sent by the then PM Narasimha Rao, brokered a deal between Karnataka chief minister Veerappa Moily and Jayalalithaa to set up a committee that would monitor flow of Cauvery water into Tamil Nadu.

On 18 September 2002, a Karnataka farmer jumps to his death into the Kabini reservoir to protest against the release of water to Tamil Nadu. All through the 1990s, Cauvery continued to be an issue that affected not just the farmers on both sides but also the electorate, to whom the Cauvery became a symbol of regional identity.This continued with no visible solution until 5 February 2007, when the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal declared the final award (arrangement of water distribution).

Expand4. What’s With the Tribunal?

Formed on 5 February 2007, the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal is based on the 1892 and 1924 agreements between erstwhile Madras Presidency (Tamil Nadu) and the princely State of Mysore (Karnataka). The current Supreme Court judgment upholds the final order of the 2007 tribunal, which upheld the 1892 and 1924 agreements, except for the modifications in the overall water-sharing.

The implementation of the tribunal has been problematic. Between 1991 and 2011, over 20 years, Karnataka released less than the stipulated amount of water to Tamil Nadu on 13 different occasions.

The only time both states attempted an amiable solution was in 2006, when farmers from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, independent of the government, came together for six rounds of talks to implement what was termed a ‘distress sharing formula.’It was in 2007, a year after this, that the final order of the Cauvery Water Disputed Tribunal, set up over 16 years earlier in 1990, was released.

Expand5. Where Does the Issue Stand Now?

On Monday, 9 April 2018, the Supreme Court pulled up the Centre for delaying the implementation of the scheme. It also asked the Centre to draft the scheme by 3 May, refusing to defer the issue by three months.

The Centre delayed the framing of the scheme saying it was an ‘emotive issue,’ and one that is bound to cause unrest among the people. With elections in Karnataka round the corner, the Centre believed that the implementation of the verdict would cause undue unrest, and be detrimental to a smooth election.

Tamil Nadu moved the Supreme Court seeking contempt proceeding against the Centre. It blamed the Centre for ‘wilful disobedience’ in carrying out the Supreme Court’s direction in setting up the CMB (Cauvery Management Board).

At the same time, the Central government filed the clarification petition.It was in response to Tamil Nadu's move and the Centre's petition that the Supreme Court fixed the deadline for the formulation of the scheme by 3 May.

The implementation of the court's verdict would hold for the next 15 years, according to Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra.

Expand6. Will the Verdict Resolve the Dispute?

At present, neither the government in Tamil Nadu nor Karnataka is keen on the immediate implementation of the verdict, with elections looming round the corner.

The question is not ‘if’, but ‘when.’Despite the fact that politicians on both sides have blown the issue out of proportion, the Supreme Court’s insistence in forming the ‘scheme’ and enforcing the verdict is a welcome intervention. In that it is a concrete step towards resolution of the issue.

Nevertheless, Tamil Nadu's insistence on the formation of the Cauvery Management Board might complicate issues. Already there is growing support among the public for a CMB and a multi-pronged push by the Opposition, who have united over the issue, led by the DMK.

An alternate viewpoint, though, is that the apex court need not have asked for a separate scheme if it was already in agreement with the verdict of the 2007 Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal. This would only result in further delay.Expand

What is the ‘Cauvery Issue’?

The Cauvery is a perennial river that originates in Karnataka, and flows through Tamil Nadu into Puducherry. It merges with the Bay of Bengal. It is Tamil Nadu's only perennial river and currently the source of over 70 percent of canal irrigation that supplies water to the state's agricultural lands. A number of districts in central and western Tamil Nadu, as well as parts of Madurai and Ramanathapuram, have come to depend on Cauvery for drinking water as well.

Equitable and timely sharing of water by Karnataka to Tamil Nadu, therefore, is vital to both agriculture and drinking water needs of TN.

For decades, the two states have fought over the timeliness, frequency, and quantity of water that each is entitled to. This issue has also been an electoral issue, and a means of polarising the two states against each other.

On 16 February 2018, a special bench of Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra delivered the verdict on the issue, largely upholding the water-sharing arrangements finalised by the Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal (CWDT) on 5 February 2007.

An important change from the CWDT arrangement was that the Supreme Court awarded an additional 14.75 tmcft (thousand million cubic feet) to Karnataka, keeping in mind the growing drinking water needs of Bengaluru, which it said had attained ‘global city’ status.

Tamil Nadu's share was therefore brought down to 177.25 tmcft from the earlier 192 tmcft. The court further directed Tamil Nadu to tap into 10 tmcft of ground water, roughly half of the existing stock of an 'empirical' 20 tmcft.

The CWDT had not taken the ground water reserves into account while awarding the water sharing arrangement. The Supreme Court also directed the Centre to formulate a 'scheme' to implement the verdict.

Herein lies the controversy.

Why is Supreme Court’s 16 Feb Verdict Problematic?

The issue lies in the differing interpretations of the verdict by Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, specifically with regards to the formulation of a 'scheme' for 'implementation of the verdict.’

According to Tamil Nadu media, government, and consequently the electorate, the formation of the scheme includes the formation of the Cauvery Management Board (CMB) and the Cauvery Water Regulations Committee. The CMB would be an autonomous body that would ensure water distribution as per the verdict, and would function independent of Karnataka or Tamil Nadu but include stakeholders from both states.

But Karnataka's Water Resources Minister MB Patil stated clearly that the SC order does not include the constituting of a 'board.’ According the minister, the state is open to the formulation of a scheme to implement the verdict.

The formation of the CMB would wrest control of Cauvery's waters out of Karnataka's hands.

The government at the Centre could agree to the formation of the CMB as part of formulation of the 'scheme' to implement the verdict, owing to pressure from Tamil Nadu. If this happens, it is possible that Karnataka might protest.

Tamil Nadu wants a board which will ensure timely release of water as per the 2007 tribunal’s final order. This has been Tamil Nadu’s biggest grouse against Karnataka.

It was to address this that in May 2012, the then chief minister of TN J Jayalalithaa requested the then prime minister Manmohan Singh to convene a meeting of the Cauvery River Authority immediately. The Cauvery River Authority, under the prime minister, was a monitoring body that was to ensure the implementation of the 2007 tribunal.

Jayalalithaa’s complaint against Karnataka was that the state had been unjustly utilising the water for summer irrigation (almost 41 tmcf), thereby severely depleting storage during summer; also that water was released only during the rainy season when the reservoirs start to have surplus.

For Tamil Nadu, the formation of the CMB is mandatory in order to stop Karnataka's discrepancies in sharing water, which have historic precedence.

When Did it All Begin?

An agreement between the then Madras State (Tamil Nadu) and the princely State of Mysore (Karnataka) was signed in 1924 and came to an end In 1974. This agreement was actually a continuation of an earlier agreement signed in 1892.

From 1970 onwards, Tamil Nadu (then Madras State) had been asking the Supreme Court to set up a system for distribution of Cauvery water equitably.

Finally in 1990, for the first time, the Supreme Court directed the Centre to constitute a Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal (CWDT). While the CWDT went about its fact-finding mission, Tamil Nadu sought interim relief.

The CWDT, thanks to the intervention of the Supreme Court, ordered Karnataka to release 205 tmcft, which Karnataka refused to oblige to.

In 1993, Tamil Nadu CM Jayalalithaa went on a sudden fast at the MGR memorial in Chennai, demanding the state’s share of water as per the interim order.

After 80 hours, VC Shukla, the Water Resources Minister sent by the then PM Narasimha Rao, brokered a deal between Karnataka chief minister Veerappa Moily and Jayalalithaa to set up a committee that would monitor flow of Cauvery water into Tamil Nadu.

On 18 September 2002, a Karnataka farmer jumps to his death into the Kabini reservoir to protest against the release of water to Tamil Nadu. All through the 1990s, Cauvery continued to be an issue that affected not just the farmers on both sides but also the electorate, to whom the Cauvery became a symbol of regional identity.

This continued with no visible solution until 5 February 2007, when the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal declared the final award (arrangement of water distribution).

What’s With the Tribunal?

Formed on 5 February 2007, the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal is based on the 1892 and 1924 agreements between erstwhile Madras Presidency (Tamil Nadu) and the princely State of Mysore (Karnataka). The current Supreme Court judgment upholds the final order of the 2007 tribunal, which upheld the 1892 and 1924 agreements, except for the modifications in the overall water-sharing.

The implementation of the tribunal has been problematic. Between 1991 and 2011, over 20 years, Karnataka released less than the stipulated amount of water to Tamil Nadu on 13 different occasions.

The only time both states attempted an amiable solution was in 2006, when farmers from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, independent of the government, came together for six rounds of talks to implement what was termed a ‘distress sharing formula.’

It was in 2007, a year after this, that the final order of the Cauvery Water Disputed Tribunal, set up over 16 years earlier in 1990, was released.

Where Does the Issue Stand Now?

On Monday, 9 April 2018, the Supreme Court pulled up the Centre for delaying the implementation of the scheme. It also asked the Centre to draft the scheme by 3 May, refusing to defer the issue by three months.

The Centre delayed the framing of the scheme saying it was an ‘emotive issue,’ and one that is bound to cause unrest among the people. With elections in Karnataka round the corner, the Centre believed that the implementation of the verdict would cause undue unrest, and be detrimental to a smooth election.

Tamil Nadu moved the Supreme Court seeking contempt proceeding against the Centre. It blamed the Centre for ‘wilful disobedience’ in carrying out the Supreme Court’s direction in setting up the CMB (Cauvery Management Board).

At the same time, the Central government filed the clarification petition.

It was in response to Tamil Nadu's move and the Centre's petition that the Supreme Court fixed the deadline for the formulation of the scheme by 3 May.

The implementation of the court's verdict would hold for the next 15 years, according to Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra.

Will the Verdict Resolve the Dispute?

At present, neither the government in Tamil Nadu nor Karnataka is keen on the immediate implementation of the verdict, with elections looming round the corner.

The question is not ‘if’, but ‘when.’

Despite the fact that politicians on both sides have blown the issue out of proportion, the Supreme Court’s insistence in forming the ‘scheme’ and enforcing the verdict is a welcome intervention. In that it is a concrete step towards resolution of the issue.

Nevertheless, Tamil Nadu's insistence on the formation of the Cauvery Management Board might complicate issues. Already there is growing support among the public for a CMB and a multi-pronged push by the Opposition, who have united over the issue, led by the DMK.

An alternate viewpoint, though, is that the apex court need not have asked for a separate scheme if it was already in agreement with the verdict of the 2007 Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal. This would only result in further delay.