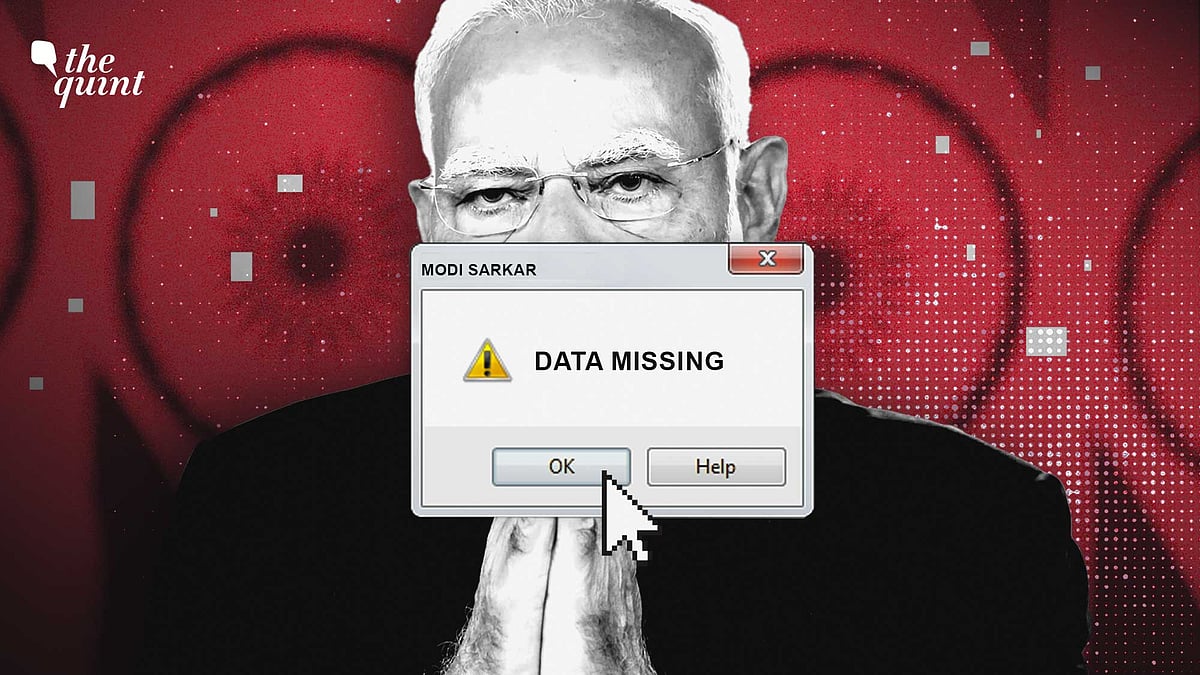

Why is Modi Govt Hiding Critical Data? Who is Benefiting from This Data Denial?

What is common in population census, hate crimes, real GDP growth, jobs, Covid-19 deaths, AQI and 'Vote Chori'?

advertisement

What is common in population census, crime data, hate crimes, household consumption, India's real Gross Domestic Product (GDP), employment, Covid-19 deaths, Air Quality Index (AQI) and the Congress' Vote Chori allegations?

Answer: A deliberate data denial by the Narendra Modi-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government. Either the government has not collected data for so long that it is absent, or there is indeed no data, or sometimes it is calculated in a way which doesn’t align with global standards, other times the government rejects global findings, and often it is seen gatekeeping data.

In fact, the Union government recently informed the Parliament that there is no data on the number of Right to Information (RTI) applications which were returned with no data or denied information in the last five years, as the Central Information Commission (CIC) does not compile such data.

The question is why is the Modi government not maintaining critical data? So much so that senior Congress leaders, including former finance minister P Chidambaram, have on several occasions taunted Modi’s NDA government to mean: "No Data Available."

But, no data doesn’t mean no crisis. In the absence of these data sets, how is the Modi government identifying vulnerable groups and ensuring that the welfare schemes (which are funded by the taxpayers' money) are reaching the beneficiaries. In this story, we unpack how the NDA government's data denial is costing the common citizens:

Population Census

Recently, India surpassed Japan to become the fourth largest economy in the world. But what if I were to tell you that our 4.18 trillion-dollar economy is making most of its internal policy decisions based only on approximations, that its welfare schemes are relying on guesswork and stale data? Why?

Because it will have been more than 15 years when India gets its updated population census in 2027. The last decennial census was published in 2011; the next was scheduled to take place in 2021 but had to be postponed due to Covid-19 pandemic and has still not been conducted.

In December 2025, the Union Cabinet approved the proposal for conducting Census of India 2027 at a cost of Rs 11,718.24 crore. It also announced that the 2027 Census will include a caste enumeration of the population as well.

The population census is the backbone of governance. It tells the government about:

the door-to-door count of the age, gender, (and now) caste of its citizens;

housing, urbanisation, migration and the workforce structure;

where welfare schemes should be targeted;

how Assembly and Parliamentary seats should be delimited; and

how much money should the states and local bodies be allocated.

Without a census, a policy is built on estimates.

Although India stated the Covid-19 led lockdowns as the reason for the delay, several countries including the US, UK, Brazil, Indonesia and Bangladesh, conducted their census between pandemic years 2020 and 2022.

"The biggest failure in India's data collection is the absence of the population census. The census is not a survey. It is a complete house-to-house collection of data. Unlike just taking 100 and then projecting, it's supposed to look at everything. And without that, we can't even estimate inflation because the census actually collects what people spend on. It works out patterns. Without it, how do we know?" said senior journalist and political economist Aunindyo Chakravarty.

Household Consumption

Another such critical data set is the Consumer Expenditure Survey, which informs the government about how people live, what they eat, how they earn and spend. This survey was conducted once every five years until 2011.

The last survey, which was conducted for 2017-18 and published in 2019, was junked by the government citing "data quality issues." However, a leaked draft of the said survey reportedly showed a decline in consumer spending in rural India and rise in poverty levels.

In 2022, the Centre replaced the survey with a new one — the first Household Consumption Expenditure Survey was conducted for 2022-2023 and released in February 2024.

So for ten whole years, the Modi government had no official, up-to-date household consumption or poverty dataset even as it continued to dole out scheme after welfare scheme for the country’s poor. This prolonged vacuum includes the Covid-19 pandemic years from 2020 to 2022, when such data was needed the most to assess:

How many more people slipped into poverty during the pandemic?

How deep was consumption shock among the most vulnerable communities?

How many people dropped out of the workforce?

The result – beneficiaries entitled to welfare schemes ended up being excluded simply because they were not counted.

On being asked how the Union government ensured that welfare schemes were indeed reaching the beneficiaries in the absence of these critical data sets, Chakravarty contended, "I think the data is available and that is the election results. Very clearly, if the poor everywhere have voted for the existing government, then you know it has reached them. We do know that when Rs 10,000 was given in Bihar, the incumbent government came back to power."

"I think that there is a certain degree of success in targeting and giving subsidies to people, which shows up in the support for the existing governments in various places. And when it fails, governments are thrown out," he added.

Chakravarty, however, asserted that the bigger question was access to data. He told The Quint, "Surveys are taking place. But they are not public. Data is being collected— who has access to that data, that is the bigger question."

Data on Covid-19 Deaths

It would be fair to say that along with the day-to-day functioning of the country, all of the corresponding data was also locked down by the Modi government during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Remember how the pan-India lockdown had compelled migrant workers to walk hundreds of thousands of kilometres back to their villages — a scene memorably captured in Homebound, India’s official Oscar entry this year. Well, when asked in Parliament about the number of migrant workers who lost their lives during this transit, the government responded saying it did not possess any such data.

In fact, when the government was asked about the number of health workers, police personnel, and sanitation workers who contracted Covid-19 and lost their life in the line of duty, it had no data.

The government did not have any data on the number of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) which were shutdown during the Covid-19 pandemic, Union Minister Nitin Gadkari told the Parliament in February 2021 even as the BJP government announced many schemes under the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan for Covid-hit MSMEs to recover. It was only in March 2025, that Union MoS for MSMEs Shobha Karandlaje told Rajya Sabha that more than 75,000 MSMEs had shut between 2020 and 2024.

Again in 2022, when the health ministry was asked about data on Covid-19 deaths due to shortage of oxygen, the Union Government said that it had sought the same from states and Union Territories—few have responded but none has reported a confirmed death due to oxygen shortage.

And as per the government’s own data on deaths and births, which it quietly released in May last year when India was in a war-like situation with Pakistan, there were nearly 20 lakh more deaths in India in 2021.

Union Health Ministry officials reportedly said that the excess mortality was not necessarily due to direct COVID-19 deaths, and included "reported and unreported COVID-19 deaths, deaths due to all other causes, and possible indirect effects of COVID-19."

Economic Growth

And since we spoke of undercounting, let’s also talk about overestimating, particularly India’s real GDP growth.

Months after he took charge as the Prime Minister, Modi’s government changed the base year as well as the methodology for computing India’s real GDP. The immediate result was higher GDP estimates and no means to compare India's growth data with that during the Congress-led UPA years (as the back-series GDP data wasn't released until November 2018).

In fact, Arvind Subramanian who was the Chief Economic Advisor then, argued that the change in methodology for computing GDP had overstated India’s growth by at least 2.5 percentage points.

In November 2025, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) gave India a “C” grade – the second-lowest possible – on its financial data quality and national accounts statistics. It pointed out that India was still using 2011–12 as the base year for estimating real GDP—even after a decade when the structure of the economy has changed substantially— and that "methodological shortcomings are hampering economists and policy-makers from getting an accurate and timely picture of the Indian economy."

When compared to the US or UK, it is seen that India relies on an outdated base year, a flawed deflation method and on proxy indicators to compute GDP, which arguably understate inflation and overstate the strength of India’s economy.

On being asked if India's real GDP growth was palpable or tangible on the ground, Chakravarty argued, "If profits rise very highly, GDP will go up. But that profit is neither being spent on investment nor is it being given to middle class professionals as salaries."

However, he said that GDP has grown for the poorest people. "The fact that there's been a return to villages suggests that life in villages is slightly better for the poorest people than it is by say, working 12-16 hours a day on a construction site. The poorest are doing better; but in what way? Subsistence existence."

Next month, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced that the base year for computing real GDP would be revised in February 2025.

Crime Data

Coming back to datasets, where prolonged delay hits us where it hurts the most. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB)’s Crime in India report, which is expected to provide a comprehensive set of crime data, has faced repeated delays.

The report for the year 2023 was published in late 2025. So there is not only a void in timely tracking changing crime trends, but also any action —including policy reforms for crime prevention or allocation of police resources — is retrospective instead of being proactive.

For instance, cyber crime cases rose by over 30 percent in India in 2023, which state governments have realised only in 2025. The question is, have the number of cybercrime police stations grown accordingly? Have cyber cells been given enough resources to monitor the shift in the nature of cybercrimes and prevent them?

Not only that, NCRB's Crime in India report misses critical context on the underlying reasons of a particular crime, such as poverty, unemployment or, even polarisation.

Which is why, when the Union Home Ministry was asked about the number of mob lynchings and hate crimes against religious minorities between 2017 and 2022, it told the Parliament that "no separate data was maintained on these crimes." It said that though NCRB collected this data in 2017, it was found to be “unreliable” and the exercise was discontinued.

Besides, mob lynching was not even defined as a crime then. And though mob lynching is now defined in India’s new criminal law Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023, there is still no data on the increase or decrease of such crimes in the last ten years.

More Crime, Still No Data

And then there is no data on crimes—that do take place, but the government claims they are not defined as such.

Remember when students pointed out large-scale irregularities, including paper leaks, in the most coveted medical entrance exam— National Eligibility Cum Entrance Test (NEET). It had led to country-wide protests; but when the Union Education Ministry was asked about data on paper leaks in the exams it conducts, it said that there is no data.

In December 2024, when asked about the number of students belonging to marginalised communities who faced caste-based discrimination or harassment at Central universities and educational institutions, the Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment Dr Virendra Kumar told the Lok Sabha that such data was not centrally maintained. However, data submitted by the University Grants Commission (UGC) to a parliamentary panel and the Supreme Court reportedly shows that complaints of caste discrimination have increased by 118 per cent in the last five years.

Further, there is no data on medical interns at government hospitals, who died by suicide; or the number of RTI Activists who have been killed in the last 10 years.

Electoral Data

It’s one thing to not maintain data. It’s another to actively control access to whatever little exists.

When Rahul Gandhi alleged large-scale voter fraud—including fake, duplicate, or bulk-registered voters in Karnataka and Haryana — and demanded:

a machine-readable voter list,

longer retention of CCTV/webcast footage, and

access to form 6&7 data

to audit and verify results, what did the Election Commission do? It dismissed everything, including its own accountability.

Delhi's AQI Data

And saving the biggest smokescreen for the last — Delhi’s AQI data.

Till now we saw that critical data was either missing or suffered prolonged delays. But this is a classic example of how the government manipulates data throughout: starting from data collection, then calculation, standardisation, and assertion.

The point is Delhi’s PM 2.5 concentration was 18 times more than WHO’s prescribed limit. No matter what, women, children, and elderly in India’s capital city are being exposed to poisonous air for at least three months each year.

The cherry on the cake: The government recently told the Parliament that it did not have any conclusive data which establishes a connection between worsening AQI and lung diseases. This, when a Lancet study attributed millions of deaths in India to air pollution since 2021.

From covid deaths due to oxygen shortage in 2020 to respiratory deaths due to air pollution in 2025, PM Modi has completed another five years of governing the world’s largest democracy without addressing a single press conference or publishing critical data—even as the common citizen continues to be on ventilator.

But if granular and timely data is essential for better governance, then who is benefiting from the government's data denial?

We at The Quint will continue to ask the tough questions to hold the authorities accountable. Please support us by becoming a member.