When Governors Become Disruptors of Federalism: The Case of Tamil Nadu & Kerala

What happened in Tamil Nadu and Kerala is not a regional quarrel. It is a national warning, writes John J Kennedy.

advertisement

What unfolded earlier this week in the Tamil Nadu and Kerala legislative Assemblies was not a clash over protocol or personality. It was a constitutional moment that exposed how the office of the Governor, once envisioned as a stabilising link in India’s federal system, is increasingly being used as an instrument of political disruption.

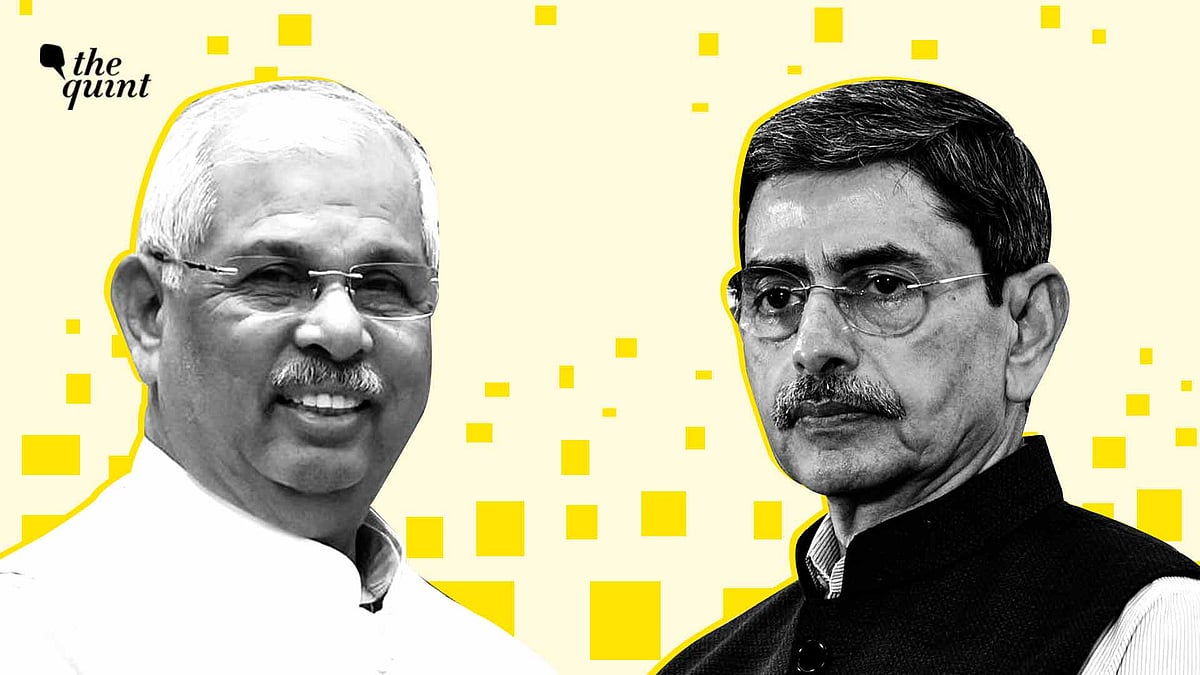

At the centre of this confrontation is Tamil Nadu Governor RN Ravi, who for the third consecutive year, refused to deliver the customary address to the Assembly and walked out.

What followed made matters worse. Within minutes, Lok Bhavan released a detailed three-page explanation, clearly prepared in advance. This was not an impulsive reaction. It was a calculated act.

A Pattern, Not an Aberration

It is important to note that RN Ravi’s ‘unconstitutional’ behaviour did not begin yesterday. It has evolved steadily:

In 2022, he skipped portions of the address.

In 2023, he inserted personal remarks.

In 2024, he read only the opening paragraph.

In 2025 and 2026, he refused to read the address altogether and walked out.

This escalating defiance is important because it clearly shows intent. It shows that the Governor’s office is no longer merely interpreting conventions but actively challenging the authority of the elected Assembly.

The stated reason this time was that the speech contained “misleading and unsubstantiated claims.” However, the fact that the address also contained criticism of the Union government for denying funds, delaying projects, and weakening fiscal federalism through cesses and surcharges cannot be missed. In other words, the inference that the objection was not merely procedural but political is quite natural.

What the Constitution Allows

Article 176 of the Constitution mandates that the Governor shall address the Legislature at the beginning of the first session of every year.

This understanding was later reinforced by the Sarkaria Commission (1988), which warned that Governors should not see themselves as agents of the Centre. It clearly stated that the Governor’s address must reflect the views of the elected government and that discretion has no place in this function.

The Punchhi Commission (2010) went further, cautioning that the misuse of gubernatorial discretion could destabilise Centre–state relations and recommending fixed conventions to prevent political misuse of the office.

RN Ravi’s refusal to read a Cabinet-approved speech directly violates these principles.

Can Governors decide what is ‘permissible’ speech?

Perhaps the most troubling implication of the Tamil Nadu and Kerala episodes is the precedent they seek to establish: that a Governor can refuse to articulate criticism of the Union government.

This leads to an unavoidable question: If Governors can decide what is acceptable in a state Assembly, what prevents the President from doing the same in Parliament?

What if a President refuses to read references to unemployment, farm distress, or communal violence because they are “misleading”? The logic is identical. The outcome would be the hollowing out of parliamentary democracy itself.

Kerala: Editing by Stealth

Unlike in Tamil Nadu, the Kerala Governor did not stage a walkout. Instead, he quietly altered the speech. References to “adverse Union government actions” were softened. A paragraph noting that Bills passed by the Assembly were pending with the Governor and that the matter was before a Constitution Bench was omitted altogether. Assertions about tax devolution being a constitutional right were prefaced with distancing language: “my government feels”.

The Supreme Court, in cases such as Shamsher Singh vs State of Punjab (1974), has made it clear that the Governor must act on the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers except in narrowly defined situations. Delivering a policy address is not one of those exceptions.

The Myth of the ‘Neutral’ Governor

Supporters of such gubernatorial actions often argue that Governors are merely upholding constitutional propriety. But neutrality cannot be selective.

When Governors repeatedly object only to those parts of speeches that criticise the Union government—and never to praise, silence, or alignment—the claim of impartiality collapses. The office then loses its constitutional umpire status and becomes a political player.

Against this backdrop, Chief Minister MK Stalin’s statement that Tamil Nadu will seek to abolish the Governor’s address altogether is extraordinary. At the same time, it is also revealing. When conventions are repeatedly violated, states will inevitably seek structural exits.

Unfortunately, that is where this confrontation leads us: away from cooperative federalism and towards a defensive federalism in which states try to insulate themselves from constitutional offices that have become adversarial. The Sarkaria Commission warned decades ago that the misuse of the Governor’s office would erode trust and provoke confrontation. That warning now appears prophetic.

The Higher Democratic Cost

Governors are not elected. Yet their actions increasingly shape legislative functioning and public discourse. When a Governor walks out of the House, he is not embarrassing the government. He is disregarding the mandate of the electorate. When a Governor edits or refuses to read a Cabinet-approved speech, he is not defending the Constitution. He is overriding democratic choice.

India’s Constitution relies not only on written provisions but on restraint, convention, and good faith. When those disappear, no amount of legal text can save institutions from decay.

What happened in Tamil Nadu and Kerala is therefore not a regional quarrel. It is a national warning. If constitutional offices are allowed to be weaponised to discipline states, the federal idea itself is diminished. The question before us is stark: Will India remain a Union of states governed by constitutional trust, or drift towards a system where unelected authorities routinely undermine elected governments?

The answer will define the future of Indian federalism.

(P John J Kennedy, educator and political analyst based in Bengaluru. This is an opinion article and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined