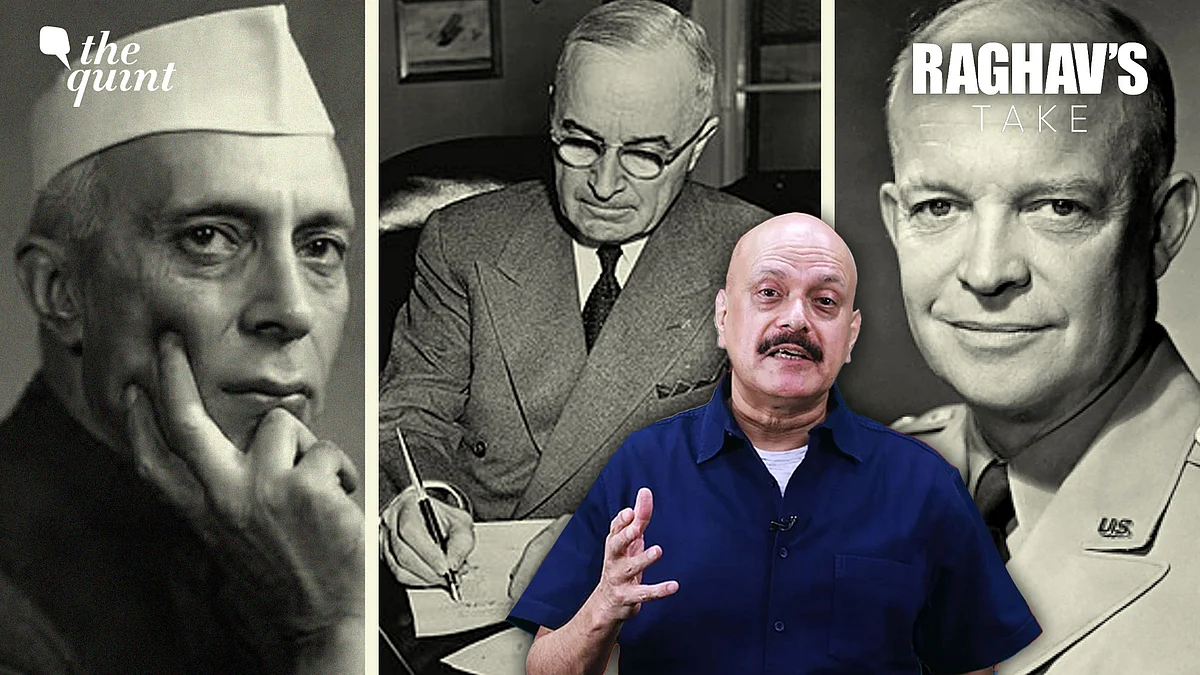

US-India-Pak: Stubborn Nehru, Unctuous Pakistan Through Truman-Eisenhower Years

The friction over Kashmir set the tone for the entire America–India relationship in the Nehru years.

advertisement

Foreword: For over two decades, America and India have been unflinching strategic allies, while Pakistan had become an outcast after Osama Bin Laden was found hiding in Abbottabad in 2011. But President Donald Trump’s open dalliance with Field Marshal Asim Munir, crypto deals with Pakistan, threatened hyphenation of that rogue state with India, attempts to intervene in Kashmir, and repeated assertions of “I ordered the India-Pakistan ceasefire in Operation Sindoor”, despite India’s overt snubs and denial, have thrown a monkey wrench in the equation. Is America swinging back towards Pakistan? Or simply nettling India? Why? In fact, Trump’s unpredictable U-turns have reopened the doors to a fascinating replay of history since the 1940s – how the personalities of successive American presidents have had an outsized impact on the quicksilver, vacillating America-India-Pakistan equation.

Here’s Part 1, where we decipher the early years after Independence, under Presidents Truman and Eisenhower.

Since the partition of the subcontinent, the US has routinely found itself allied more closely with Pakistan than with its fellow English-speaking democracy, creating one of the oddest and most complicated friendships of the twentieth century.

During World War II, US President Franklin Roosevelt, an avowed anti-imperialist, had staunchly supported India’s independence movement, repeatedly pressuring British prime minister Winston Churchill to set it free—in part to secure India’s commitment to the Allied war effort.

But by the time the British Raj quit India, Roosevelt was dead and the US was preoccupied with fighting Communism. Washington didn’t pay much attention to the division of the subcontinent, or the horrific sectarian violence that accompanied it.

The Socialist Hangover

Still, the socialist bent of India’s first leaders worried the US. Jawaharlal Nehru articulated India’s nonalignment policy early on, but he clearly had a soft spot for the Soviet Union.

‘We have to be on friendly terms with both Russia and America,’ he wrote in a letter to his sister, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, who was representing India at the inaugural meeting of the United Nations in 1946, but 'personally I think that in this worldwide tug-of-war there is on the whole more reason on the side of Russia'—adding diplomatically, 'not always of course.'

Pakistan soon helped drive the first real wedge between India and the US—Kashmir. During partition, the British had urged each of the more than 350 princely states to join either India or Pakistan. All but a handful did. The ruler of Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh, a Hindu governing a majority Muslim population, initially gestured toward Pakistan but then hesitated. While he was dithering, Pathan tribesmen backed by Pakistan swooped in from the Northwest Frontier and threatened to take the capital, Srinagar.

The panicked Maharaja turned to Delhi for help, agreeing to join India, which sent soldiers to beat back the Pathans.

Kashmir and the US

After the 1949 ceasefire, Nehru exhibited the proud, stubborn, independent streak that would guide his country’s foreign policy for decades to come. He told the US ambassador in Delhi that he was ‘tired of receiving moral advice from the United States’ and would not back down, ‘even if Kashmir, India, and the whole world went to pieces.’

The Truman administration was irritated by neutral India’s refusal to side with the forces of democracy and bristled at Nehru’s suggestion that the West recognise Communist China and deal more amicably with the Soviets. When Washington welcomed Pakistan Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan shortly after his visit, Nehru was miffed.

‘The Americans are either very naïve or singularly lacking in intelligence,’ he wrote to his sister. ‘They go through the same routine whether it is Nehru or the Shah or Liaquat Ali… It does appear that there is a concerted attempt to build up Pakistan and build down, if I may say, India.’

Truman to Eisenhower

US aid became another source of tension. After partition, India’s biggest need was for food assistance, which President Truman readily agreed to provide.

However, Congressional bickering, combined with a series of diplomatic misunderstandings and miscommunications, delayed passage of a bill promising $190 million of wheat until June 1951.

North Korea’s invasion of South Korea in 1950 made Washington more determined than ever to halt Communism’s spread, and India remained essential to that goal; a National Security Council document outlining the first formal South Asia policy concluded that if India were lost to the Communists, ‘for all practical purposes all of Asia would have been lost.’ In 1952, the Truman administration enthusiastically agreed to send Delhi 200 Sherman tanks, as well as fifty-four transport aircraft. Pakistan, which had been angling unsuccessfully since partition for US arms assistance, vehemently protested the sale, calling it an unfriendly act that would upset the region’s military balance—a charge the US dismissed as overblown.

He was determined to stop Communism from marching westward, and he saw Pakistan as a key component of the ‘northern tier’ of that defense. During a trip to South Asia that May, Dulles gushed about the warm reception he encountered in Karachi—‘a genuine feeling of friendship’—compared to Nehru’s indifference.

Ebbs and Flows in Pakistan

Pakistan Prime Minister Liaquat Ali was assassinated in 1951, and the country taken over by a conservative military leadership; the new army chief of staff, Gen Ayub Khan, was handsome, charismatic, and smooth-talking. Though his true motive for winning US support was to bolster Pakistan’s security against India, he knew better than to say it. Visiting Washington in the fall of 1953, he riffed eloquently on the dangers of Communism and the need for fighting the Red threat together. ‘Our army can be your army if you want us,’ he told Assistant Secretary of State Henry Byroade. ‘But let’s make a decision!’

Dulles was ready. There was just the formality of winning Congressional approval of the relatively modest military aid package—and the small issue of India’s reaction. Dulles asked Ayub not to say anything until Eisenhower’s administration had worked out the details, but Ayub leaked the story to The New York Times. Nehru turned apoplectic. He warned that by giving arms to Pakistan, the US was bringing the Cold War into the region, threatening ‘very far-reaching consequences on the whole structure of things in South Asia and especially in India and Pakistan.’

In 1959, the US signed a bilateral defense agreement with Pakistan; subsequently, Islamabad agreed to allow Washington to set up military and intelligence posts on its turf. When India came looking for military equipment the following year, the US, fearful of upsetting its new ally, said yes to transport planes but no to the Sidewinder missiles it had already promised Pakistan.

In Part 2: We shall see how the America-India-Pakistan equation played out under Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson.