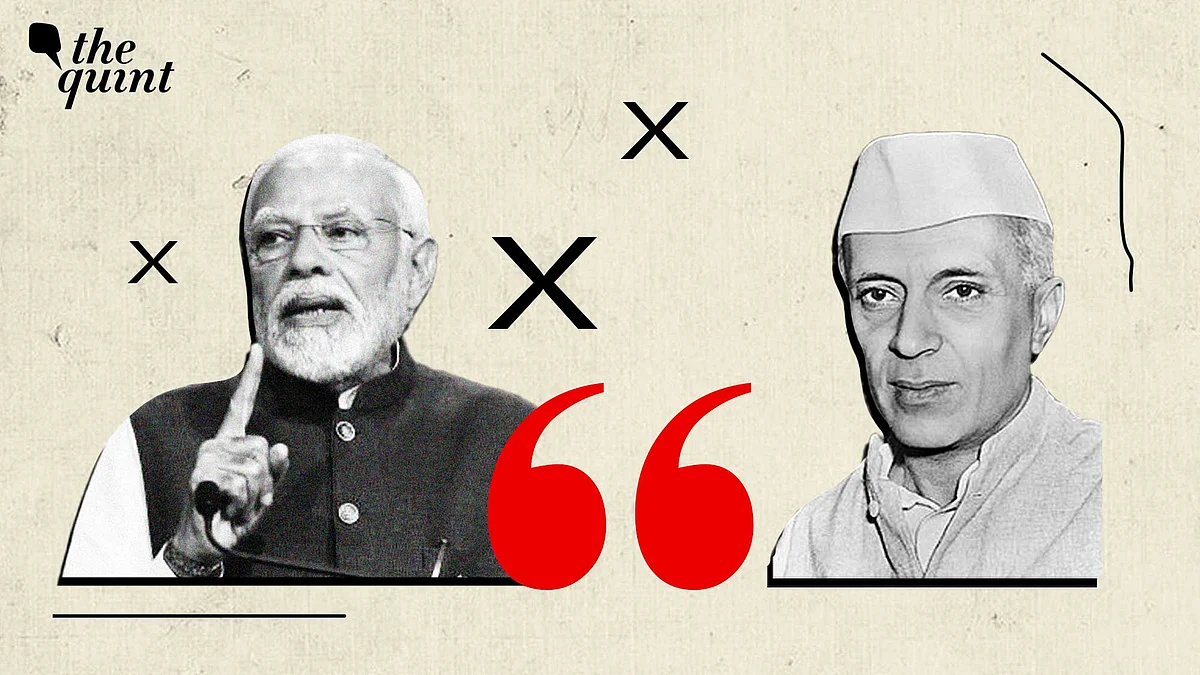

PM Modi's Podcast With Lex Fridman Has Echoes of Nehru's Old Interview

On world peace, both Nehru’s instincts and that of Modi's are essentially the same, writes Vivek Katju.

advertisement

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent participation in Lex Fridman’s podcast covered issues ranging from aspects of his early life, his philosophical grounding in the tenets of the RSS, his spiritual quests, his work ethic, his commitment to the country, and his approaches to governance and foreign policy—the latter, at a critical time in world affairs. Modi's responses showed him as a person of firm convictions who has dedicated his life to the service of the country and its people. He appeared to speak from the head and the heart.

As I read the transcript of the podcast, which was recorded in Delhi, an old memory stirred. I was reminded of Jawaharlal Nehru’s discussions with the Hungarian-born celebrated journalist and author Tibor Mende between 31 December 1955 and 9 January 1956.

Mende made a transcript of these recordings which he published in a book, Conversations with Mr Nehru, in 1956.

Mende also states that "in no single case did Mr Nehru object to or ask for the omission of any subject."

Two PMs, Two Interviews

A span of almost 70 years separates the two conversations. During this period India and the world have been transformed. Yet, it is useful to refer to Nehru’s conversations because, he then, like Modi now, enjoyed enormous popularity.

As Fridman did with Modi, so did Mende with Nehru by focusing on his upbringing and the forces that fashioned him and his outlook.

What comes through in both conversations, despite their diametrically different views on the idea of India and its historical journey drawing from their different ideologies and visions, is the passion for the country’s progress and for popular welfare. What also comes through is their focus on the resolution of contentious international issues without a recourse to violence and war. This requires a brief background.

Fridman asked Modi about the Ukraine war. Modi said:

He went on to add, “Initially, it was challenging to find peace, but now the current situation presents an opportunity for meaningful and productive talks between Ukraine and Russia.” Indeed, from the outset Modi has emphasised that the only resolution of the conflict can be on the negotiating table.

The global situation in the mid-1950s was particularly dangerous. The two ideological camps led by the US and the Soviet Union were engaged in a Cold War. They were furiously expanding their nuclear arsenals—and there was no certainty that the Cold War would not turn into a kinetic war involving nuclear weapons. Indeed, in 1962, the world came perilously close to a nuclear war during the Cuban crisis. For a statesman like Nehru, the Cold War could not lead to peace, and he was deeply concerned.

He expressed this concern during his conversation with Mende. At one point he said (and I quote in-extenso):

Tracing Affinities and Fault Lines

Nehru is often accused of being an idealist and neglecting Indian defences. He told Mende, at one stage, that Indian defence forces were competent. The events of 1962 exposed their weaknesses—and India changed course to build up its defence forces. That process has continued irrespective of the nature of government in India.

Modi spoke eloquently about Mahatma Gandhi’s role in awakening the masses during the Indian struggle for freedom. Mende too explored Gandhi's philosophy and actions with Nehru.

Naturally, Nehru was Gandhi’s acolyte even if he was sometimes at odds with his ways of thinking on the development model India needed to pursue. The texture and length of his responses to Mende on Gandhi and his contributions are naturally more enriched with personal insights.

Therein lies the crux of the essential fault line running through Indian polity and society today. That Modi's and Nehru’s responses to Fridman and Mende, respectively, make abundantly clear.

Modi places great stress on the value of personal relationships in inter-state relations. Nehru too built personal contacts and friendships but the Mende conversations show his appreciation of historical forces. That arose from a deep reading of world history and introspection during his long periods of imprisonment. He refers to the latter to Mende.

In terms of personal ties, Modi’s laudatory remarks on President Donald Trump deserve special mention. He also praises Trump for having a clear vision for what he wishes to achieve during his current term. Modi avoids going into how Trump’s approaches will impact India and the world, including global existential crises such as climate change.

Geopolitical Diplomacy

Modi’s comment that India-China ties have now turned a new leaf is an expression of hope that the scars caused by the 2020 events will fade in time. The question is whether India can now avoid incurring heavier expenditure on building defence infrastructure along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) even as economic and commercial ties improve.

Modi is correct in hoping that Pakistan will see reason and change course but that is unlikely for its hostility to India is embedded in its foundational principle. That the generals, the true rulers of the country, are sworn to uphold.

It is interesting that Modi allowed Fridman to go into the issue of the 2002 Gujarat riots. While doing so, though, Fridman carefully notes that the courts have absolved Modi of any responsibility for them. Modi’s response on the riots is on the lines he has taken in the past with one difference.

He states that he was given the responsibility of handling Gujarat as chief minister at such a time. The terrible Godhra incident provided the ‘spark’. He especially notes that there has been no riot in Gujarat in the past 22 years.

Modi’s Fridman interaction deserves a wide audience, and it would be profitable especially for scholars and those concerned with current Indian developments to also read Mende’s conversation with Nehru. Together, they give insights into India’s journey through the decades.

(The writer is a former Secretary [West], Ministry of External Affairs. He can be reached @VivekKatju. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined