What the Unnao Case Reveals About Law, Power, and Process

Without systemic reform, outrage will continue to fill the vacuum & justice delivery will inevitably bear the cost.

advertisement

The Unnao case has returned to public attention not because of any fresh finding on guilt, but because of what followed the conviction.

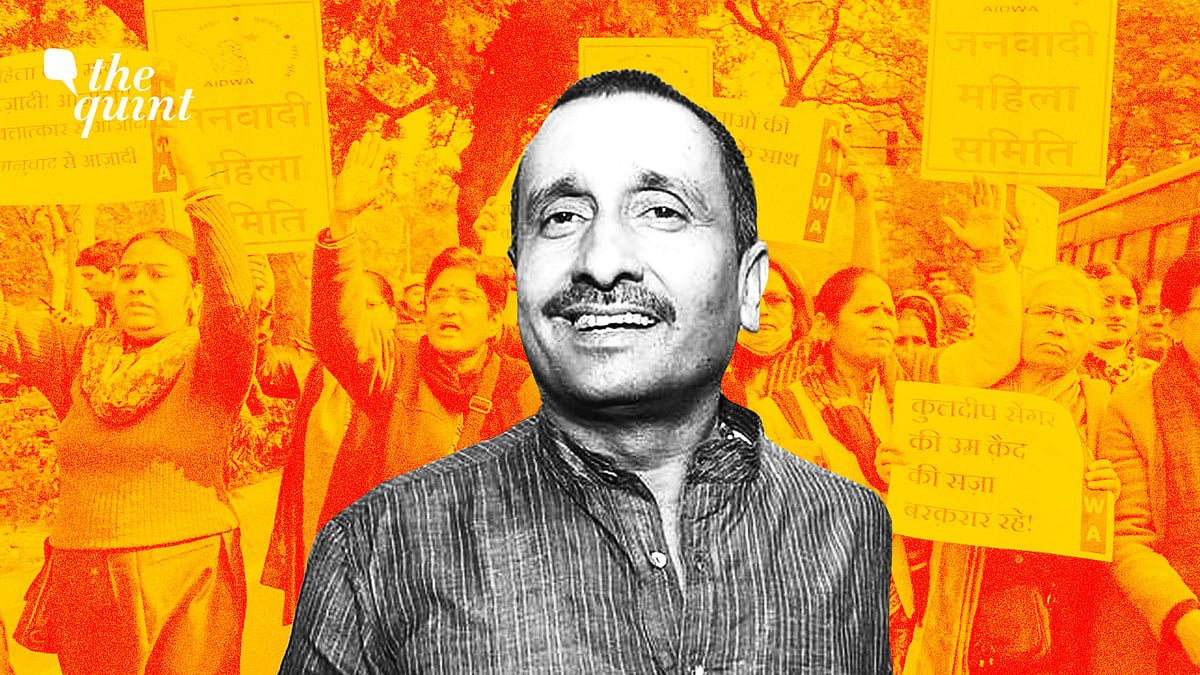

Before setting down my own thoughts, I came across an open letter authored by one of the daughters of the convicted accused, Kuldeep Singh Sengar, along with interviews given by another. These narratives exist, and they are circulating widely. Their relevance to the criminal process, however, is limited.

What the Unnao case ultimately lays bare is an unavoidable asymmetry of loss. On one side is the survivor, who lost her childhood, her father, her family’s security, and any realistic chance at an ordinary life to a system that moved slowly and shielded power. On the other are accounts of familial distress articulated through personal memory and emotional absence.

Its function is narrower and more exacting: to identify wrongdoing, to locate responsibility, and to centre the victim — especially in cases where power and impunity are part of the harm.

The Legal Backbone of the Conviction

In the Kuldeep Singh Sengar matter, the Delhi High Court was dealing not with the merits of the conviction, but with an application for suspension of sentence pending appeal. The court examined whether the statutory and judicial thresholds for interim liberty were met, particularly the fact that the appellant had already undergone a substantial period of incarceration while his appeal remained pending.

That relief, however, was short-lived. The order was promptly stayed by the Supreme Court, restoring the sentence and underscoring that the question of interim liberty in a case of this nature warranted closer scrutiny at the highest level.

The importance of this case lies far beyond interim appellate orders. The original judgment stands as a marker for how courts interpret and enforce child-protection laws, particularly in grounding the determination of a “child” under the POCSO Act in reliable documentary evidence such as school records, rather than in speculative or variable medical opinion.

When Investigation Itself Becomes a Site of Harm

Equally significant is the trial court’s candour in recording that the investigation itself was unfair and prejudicial to the survivor — a rare but necessary acknowledgment. Taken together, the case exposes a deeper structural problem: even when courts display legal clarity and resolve, institutional failures, especially at the stage of investigation, continue to shadow outcomes in even the most scrutinised prosecutions.

That tension between evidentiary caution and investigative lapse is not unfamiliar in practice and matters most for victims. I have seen courts refuse to treat call detail records as conclusive proof of alibi, recognising that cell tower location data, often presented as precise and scientific, operates within a margin of error shaped by network load, tower range, and routing variables.

Without being properly explained through expert evidence, such data cannot be elevated into unquestionable truth, particularly when its acceptance risks displacing a survivor’s account. The same caution applies to age determination: bone ossification tests are, at best, approximations with acknowledged margins of error, and cannot be mechanically preferred over reliable primary school records maintained contemporaneously.

That is precisely why technical evidence must be approached with restraint and never allowed to substitute rigorous proof in cases where the consequences for the victim are irreversible.

The “Public Servant” Definition Defense

The High Court, while considering the application for suspension of sentence, proceeded on a narrow legal footing. It accepted, on a prima facie basis, the appellant’s argument that since the term “public servant” is not defined in the POCSO Act, Section 2(2) requires the court to borrow the definition from Section 21 of the IPC.

Relying on settled precedent that an MLA is not a public servant under the IPC, the court was inclined to exclude the appellant from the scope of Section 5(c) of the POCSO Act and then carried that conclusion forward to dilute the charge under Section 376(2)(b) of the IPC as well. Once that premise was accepted, the aggravated provisions under both statutes effectively fell away.

Proceeding on that basis, the court reasoned that the conviction would then rest on Section 3, read with Section 4 of the POCSO Act. Given that the appellant had already undergone more than seven years of incarceration exceeding the minimum sentence prescribed prior to the 2019 amendment the court held that suspension of sentence could be considered, leaving all substantive issues to be examined at the stage of final hearing of the appeal.

The difficulty with this approach lies in what it sidelines. POCSO is not an ordinary penal statute; it is a special law enacted to address sexual offences against children, particularly where power and authority are involved. Section 42A expressly gives it overriding effect, and the aggravated offence provisions are meant to capture precisely those situations where the perpetrator occupies a position of dominance or public authority.

A purely literal import of Section 21 IPC, without engaging with the object of the statute, risks reducing Section 5(c) to near redundancy when the accused is an elected representative.

The more authority one wields, the lighter the legal label becomes. For a child protection law meant to deal with abuse of power, that conclusion is difficult to take seriously.

When Security Becomes Substitute for Justice

The reasons given to justify considering the accused’s release on the ground that security arrangements mitigate any threat to the survivor is deeply troubling. The record itself acknowledges that the survivor’s life was at serious risk, enough for the Supreme Court to transfer the trial out of Uttar Pradesh, grant CRPF protection, and do so against the backdrop of her father’s killing and attacks on relatives and lawyers.

To then suggest that threat perception should not weigh against the accused’s custody because security arrangements exist turns the logic on its head. Security is not a solution; it is an acknowledgment of danger.

On the other hand, one of my concerns with the blowback following the Sengar order is more on the structural side. When high-profile cases generate sustained public and media pressure, the response rarely remains confined to the facts of that case. Instead, it surfaces elsewhere quietly and unevenly.

In routine criminal matters, judges may become more hesitant to grant bail, forcing more accused to approach the Supreme Court, compounding delays, and further restricting access to justice for those without means. In this case, the question turned on a narrow legal threshold: whether the appellant had already undergone a substantial portion of his sentence while his appeal remained pending. The court answered that question in favour of personal liberty.

Had a stricter statutory bar applied, the outcome would have been different. Public discourse has since moved between the accused’s history, the survivor’s vulnerability, and the larger question of power in India. These are all real concerns, but adjudication cannot function on shifting moral terrain. The answer lies elsewhere: faster trials, faster appeals, and greater judicial capacity. Without systemic reform, outrage will continue to fill the vacuum and justice delivery will inevitably bear the cost.

(The author is partner at Tatvika Legal, A full-service law firm based in Delhi NCR. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined