‘Unishe April’: A Rare Ode to Complexity of Mom-Daughter Bonds in Indian Film

Rituparno Ghosh's deconstruction of the complexities of a mother-daughter bond remains unparalleled in Indian films.

advertisement

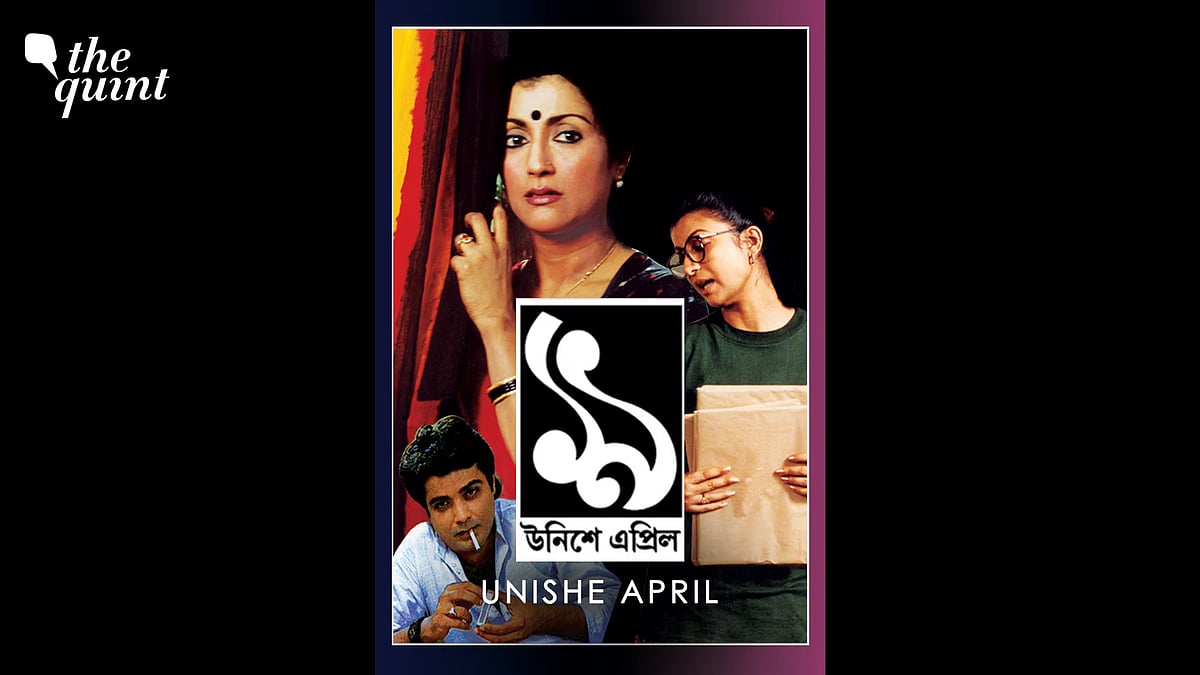

Rituparno Ghosh’s Unishe April (19th April), which bagged the top award at the National Award in 1995 along with the Best Actress Award for Debasree Roy, will be celebrating its 31st birthday this year.

It not only encompasses familiar emotions like guilt, betrayal, love, and nostalgia, but also offers deeper mediations on the role of women in society and the conflicting politics of womanhood, motherhood, and personhood.

Rituparna Ghosh, who wrote and directed Unishe April, aspired to free the censored and distorted image of the screen mother from the taboos and constraints of patriarchal culture, and place it as a subject of psychological study and sociological inspiration for a feminist reading.

Dissecting 'Unishe April'

The plotline weaves around a single day and night, that of 19 April, as suggested by the title. It’s the death anniversary of Aditi's (Debasree Roy) father, which coincides with the day her famous danseuse mother Sarojini (Aparna Sen) gets the news of having received a prestigious award for her singular contribution to the art of classical dance.

The news of the award sets in motion a chain of events that finally leads to a confrontation between the mother and the daughter, distanced through what on the surface, appears to be a clash of values, but which has grown over time, basically out of a slow and sure breakdown in interpersonal communication.

Aditi's consciousness is made up of memories of a dead father, his identity, his pain, and his alienation from his celebrity-wife, reflected as a kind of a picture-puzzle through multiple pieces of fractured flashbacks that unfold from her point of view.

The mood of the film begins to change once the camera follows the two women into the kitchen, instantly adding unforeseen degrees of intimacy to the interaction. Tins are opened, an old recipe notebook is found and then there is a search for a particular ingredient which must go into the one-dish meal.

"Let’s make it without the saffron" says Aditi, the daughter. "No" says the mother, underlining her striving for perfection in every area of life. And then, one tin reveals a long-lost bottle of French perfume Sarojini believed to have been broken long ago. "I hated that smell" cries Aditi, "because it reminded me of your absence."

The use of the kitchen further offers a perceptive insight into its own positional identity as a site of bridging woman-to-woman relationships within the home to the fore.

Despite the fact that none of the women, mother or daughter, are particularly traditionally “domestic” (neither is a housewife or adheres to typical roles ascribed to women), the fact that their tensions and contrasts play out in the kitchen underlies the inherent performativity of gender that defines characters, both in good films, or in real life, in spite of themselves.

But even though it is in the kitchen, the appearance of the perfume bottle breaks the illusion of domesticity, in a way linking both the characters’ acceptance and simultaneous defiance of gender roles.

Having played its role, it recedes once more into the background, allowing the mother and daughter to re-occupy centre-stage and reclaim their chosen personalities in the world.

The conflict is resolved in the end as truths unravel, forcing the two women to step out of their guarded silences and begin to talk.

Ghosh draws a psychological portrait of a mother-daughter relationship placed in a definite ideological, topical and social context. Aditi's dilemma arises from the real and perceived threats her mother's celebrity status posed to her own identity and interpersonal relationships. When her boyfriend tries to back out of a more permanent arrangement with her, she blames it on her mother’s stardom.

Her upbringing is marred by the psychological exploitation her father meted out to her in his desire to get even with a wife, whose fame, power and talent underscore his essential ordinariness as her husband.

Aditi hates the celebrity status she is heir to because of the negative associations they hold for her. In more recent years, films like Qala (2022), which drew on a similar mother-daughter plotline before diverging into a darker tale of fame and deception, and others, have tried to recreate the mother daughter dynamic, but rarely has any come close to the finesse of Ghosh’s quiet masterpiece.

Mother Daughter Relationships in Films

Though the mother-daughter relationship has formed the sub-theme for many Indian films within the format of cinematic melodrama, this was for the first time, perhaps, in the history of Indian cinema, that the director had used the narrative itself (conceived, written and scripted by Ghosh,) as the vehicle for diagnosing a mother-daughter conflict in ideological terms and objective categories.

Adrienne Rich has written that patriarchal culture depends upon the mother to act as a conservative influence, "imprinting future adults with patterned values even when the mother-child relationship might seem most individual and private." The dilemma of the daughter (Debasree Roy) in Unishe April springs from her screen mother's (Aparna Sen's) inability to imprint 'patterned values' based on patriarchal codes of motherhood.

Flash forward to 2012. Sridevi, one of the most successful stars of Bollywood cinema, made a startling comeback more than a decade after her marriage with Gauri Shinde-directed English-Vinglish.

A poster of English-Vinglish.

(Photo: Shoma A Chatterji)

Shashi Godbole (Sridevi) is a very efficient housewife, who runs a successful “side business” of making and selling laddus across the city to different customers.

Her husband, a corporate honcho, makes fun of her business and is overall dismissive of his wife’s entrepreneurial tendencies. He takes potshots at her skills, even though they’re making her money, and dismisses her as someone “born to make laddus”.

Does the ideal wife’s indigenous way of earning some money make him feel insecure or less of a man? One wonders so, because the laddu is a bone he cannot seem to get rid of. Shashi’s efficiency is dismissed by the daughter and the husband summarily upon a single ground – that she could not speak English fluently. The daughter feels embarrassed to have her meet the school principal.

The narrative shifts when Shashi has to rush off to New York to help her older sister with her niece's wedding. Her widowed sister, settled in the US for ages, and her two daughters are thrilled with her visit and surprisingly, her inability to speak English does not affect them at all.

Does her US-acquired proficiency in English change her status quo with her husband and daughter? They keep their silence, and they do not need to comment because it might give ideas to Shashi.

The story, in a way, reminds of my own late mother, a school drop-out who read Tolstoy translations in English and spoke broken English. She would carry on smartly, at a stretch, knowing that her grammar was all wrong and ignored the meaningful glances we threw in her direction. No one laughed because no one dared to. This was way back in the sixties.

When, once, I nervously asked her why she did not brush up her English when all her three children were there to teach her how, her immediate retort was, “Do Englishmen know our language? I am not supposed to know English at all so you must be thankful that I learnt it all by myself and am carrying on without help.” That was the first and last time I tried to correct her grammar. No one in the family, including my erudite father, dared to make any negative comments about her incorrect English.

Which brings me to my point, that English-Vinglish, though having its heart in the right place, fell for rusty tropes instead of dealing with real life tensions and complexities that underlie any relationship.

Yet another film, Mom (2017), a murder mystery directed by Ravi Udyawar, tried to invoke the mother-daughter dynamic with the protagonist (yet again played by Sridevi, incidentally) failing to create a rapport with her step-daughter.

A poster of Mom (2017).

(Photo: Netflix)

The plot eventually takes on narrative of gender violence and retributive justice, with the mother finally managing to gain the teen’s acceptance by almost single-handedly solving the mystery of the latter’s gang-rape. The achievement of vengeance comes as a kind of consolation prize for the survivor.

The mother’s desperate attempts to gain acceptance from her step-daughter and the latter’s staunch refusal to do so, define a sub-plot but could have been the main theme of the film, which instead chose to use familiar (and deeply skewed) notions of gender justice its centrepiece.

Once in a Blue Moon

There are some films that have done better, too. Few are aware that Shivendra Sinha made a film called Phir Bhi in 1971, which explored a very delicate relationship between a single mother (Urmila Bhatt), a young man (Partap Sharma), and Bambi, Urmila Bhatt’s grown daughter. It probed into a near-fragile connect between a grown daughter and her mother who finds love in her middle-age and naturally, the daughter is shocked.

Though the film turned out to be a miserable flop, Partap Sharma won the 1971 National Award for the lead role in this feature film which also won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Hindi.

We might close this intimate circle with a new Bengali film, Puratawn (ancient) (2025) directed by the NRI economist-filmmaker Suman Ghosh and produced by Rituparna Sengupta. Puratawn narrates slices of life of Mrs Sen (Sharmila Tagore), about to approach her 80th birthday, visited by her daughter Ritika (Rituparna Sengupta), a successful entrepreneur based in a different city.

A poster of Puratawn directed by the NRI economist-filmmaker Suman Ghosh and produced by Rituparna Sengupta.

(Photo: YouTube)

The son-in-law Rajeev (Indraneil Sengupta), an adventure photographer and perhaps also a geologist, lives in an ancient house in a suburban city some distance away from Kolkata. Mrs Sen’s daughter and son-in-law are going through some marital conflicts but that is not the subject of the film.

The subject, per se, is Mrs Sen who keeps waiting for her little girl ‘Mamoni’ to return from school, or, in front of the adult “Mamoni”, she prepares a tiffin for the little daughter and turns around to ask the adult Ritika “who are you?” But she is not suffering from Alzheimers, as Ritika’s psychiatrist friend tells her. She is suffering from a little-known medical syndrome called Futurophobia.

According to Frank Anderson, MD, “Futurophobia happens when the anticipatory fear is rooted in a past event or experience, it is often associated with dread, which can be physiologically intense and frequently associated with something ominous or traumatic in nature. Some form of trauma is usually at the root of a dread response.” Mrs Sen is afraid of stepping or living in the present which for her, is the ‘future’ so, often, she treks back to the past and feels both safe and secure there.

A beautifully subdued exposition of a mother-daughter relationship captured through the open river, an ill-kept garden with old trees, and a lot of shrubbery, with the lone lady of eighty trying to make sense of her life within the modernity of her daughter’s life.

Films such as these sometimes make one feel that, perhaps, a little bit of Rituparno Ghosh lives on through the consumption and reiteration of his craft that resurfaces in the least expected cultural crevices.

(This article was updated to reflect that the film has completed 31 years instead of 21 years as earlier stated. The error is regretted.)

(Shoma A Chatterji is an Indian film scholar, author and freelance journalist. This is an opinion article, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined