Kashmir's Outrage Over 'Obscene' Fashion Show Has Nothing to Do With Morality

It isn't religious dogma either that led to opposition against the fashion show, writes Shakir Mir.

advertisement

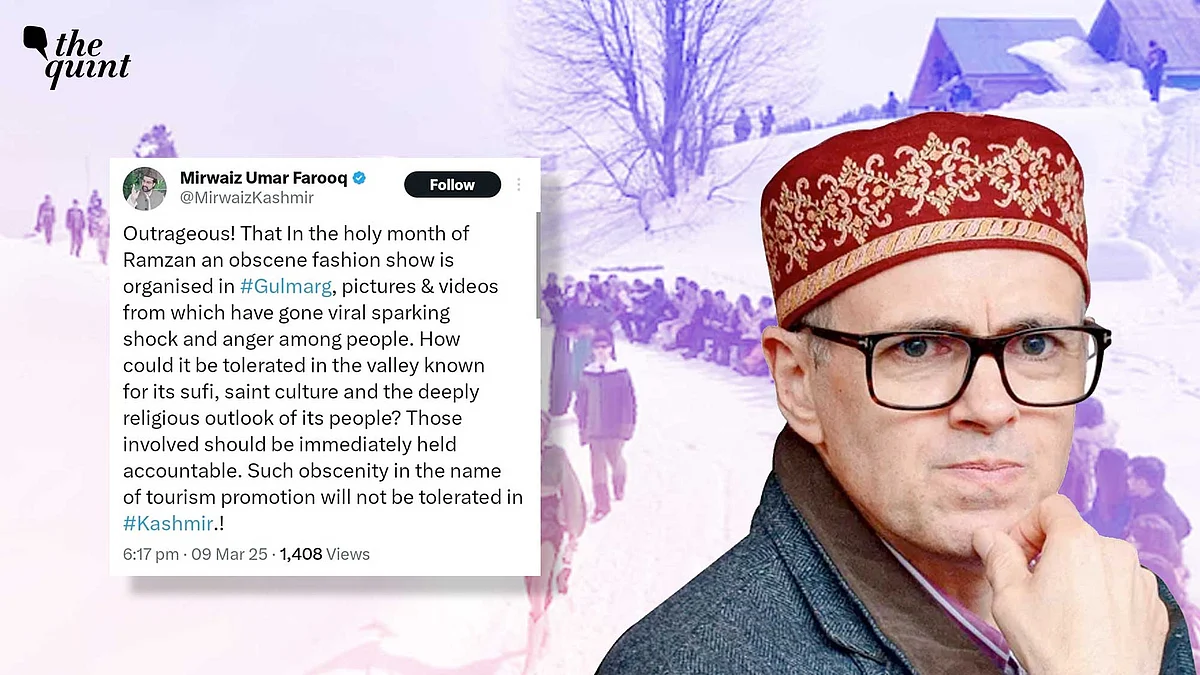

A controversy over a fashion show held in snowy Gulmarg has snowballed into a political slugfest in Jammu and Kashmir.

Put together by designer duo Shivan and Narresh, the fashion show raised many eyebrows for insulting Kashmiri sensibilities and provocating religious sentiments of the community, especially in the middle of the holy month of Ramadan. The most talked-about contentions revolved around the fashion show being "obscene", "outrageous", and against the ethos of Kashmiriyat.

While the matter became a political rallying point for politicians in J&K, the mainstream discourse over national TV and social media outside of Kashmir have mostly centred around allegations of 'obscurantism' and 'narrow-mindedness' of Kashmiris.

What's in a Fashion Show?

One of the primary reasons for the outrage in Kashmir was, of course, the fact that it was organised during Ramadan. The show drew the ire of almost all big religious and political leaders of Kashmir, with Chief Minister Omar Abdullah even calling for police action.

Nevertheless, the viral pictures from the show featuring bikini-clad models waltzing over a thick layer of snow in Gulmarg, led many to accuse the designers of being tone-deaf and insensitive to local cultural sensibilities.

The issue has remained in political headlines of the region after the District Court in Srinagar issued a ‘pre-cognisance’ notice to the directors and editors of ELLE India, on whose Instagram page the show was promoted. The posts have since been taken down.

Some news channel panelists have equated the outrage with right-wing Hindu groups forcing meat shops to shutter in other parts of the country during religious festivals like Navratri, or Uttar Pradesh authorities directing eateries along the Kanwar Yatra route to display the names of the owners, lest anyone of them turned out to be a Muslim.

The Paradox of 'Modernity' in Kashmir

It is true that there has been an increasing opposition to issues such as the proliferation of liquor vends, fashion shows, and so on in the Valley. But, unlike mainstream opinion, the opposition has less to do with embracing so-called "progressive" viewpoints and more to do with the simmering anxieties over the erosion of cultural identity and imposition of a new 'value system' by veritable outsiders, especially in the aftermath of Article 370's abrogation.

Kashmiri historians and anthropologists feel that calling the reaction "obscurantist" or an attempt to moral police is ill-forged and reductionist.

“Labeling Kashmiri opposition to ELLE India’s fashion show as 'backward' oversimplifies the issue and ignores the deeper historical reality,” Shahla Hussain, a historian and author who specialises in Kashmir studies, told The Quint.

Hussain added that the outrage underscores larger anxieties among Kashmiris over losing what she calls their “culturally informed religious identity”, resulting from the decades of gradual assimilation with India, which started in 1947 and has remained a historically contentious part of the former state’s politics.

Although Article 370 – which enshrined the constitutional autonomy for J&K – was negotiated in 1950, the successive J&K governments hollowed out the law by doing away with its major provisions, thereby giving the Union government more substantial federal powers.

While many of these measures were aimed at speeding up J&K's political, cultural, and economic integration with India, they remained controversial as they were being decided and implemented unilaterally without consulting with the people of Kashmir. Some of these changes were legislated by pro-Centre leaders, such as Bakshi Ghulam Muhammad, who are alleged to have rigged their way to power.

The Assembly elections held in J&K – in 1951, 1957, 1962, 1967 and 1972 –have all been marred by allegations of irregularities.

Some of these integration measures included getting J&K to surrender its autonomy over finances, dissolving the titles of Prime Minister and Sadr-e-Riyasat, and restricting travel across the Line of Control (which was then called the ceasefire line). Many families were torn apart because of that and continued to yearn for a reunion which never happened.

The Complex 'Integration' of J&K

Kashmiris have long viewed this integration process – rationalised in the name of secularism – with deep suspicion, not in the least because they reformulated Kashmir’s social structures, altering the values that had sustained Kashmiri society.

"This blending of 'nationalism' with 'secularism' created fears among Kashmiri Muslims, that (the Centre) was attempting to eliminate their religiously based cultural identity,” she said.

Even today, while opposing the fashion show for being ‘indecent’, the Kashmiri civil society members and public figures have invoked the famed Sufi ethos – the unique religious spirit that permeates the social consciousness in the Valley – which has helped Kashmiris survive as a community through periods of turmoil.

In October 2020, the Narendra Modi administration further amended regional land laws to allow anyone living across the country (subject to a certain criteria) to acquire land and obtain residency in the union territory of J&K.

Just how politically sensitive the issue is can be evidenced by another controversy that broke out this week following reports that former Sri Lankan cricketer Muttiah Muralitharan had been allotted 25.75 acres of land in Kathua district for his company Ceylon Beverages. The fallout of the news was seen inside the J&K Assembly where the Opposition legislators called this a “serious issue that needed to be looked into.”

Anxieties over Erasure

During the last few years, the Central government has also presided over many changes that cemented fears in Kashmir that the markers of their unique identity were either being suppressed or uprooted.

These include holding the International Day of Yoga inside the shrine of revered Sufi saint Sheikh Nooruddin in Budgam district, removing pictures of the Valley’s foremost historical leader Sheikh Abdullah from the J&K Police medal, or striking off 13 July – when Kashmiris commemorate the killing of 22 protesters during an uprising against the Dogra Hindu monarchy in 1931 – from the list of public holidays.

Additionally, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-backed Lieutenant Governor also removed Urdu’s status as sole official language in J&K. In recent times, there has been a proliferation of Hindi signboards across the union territory — a language that locals can neither speak nor write. Last year in September, the University of Kashmir celebrated ‘Hindi Diwas’ with pomp and show.

In the recent past, the BJP-led J&K Waqf Board has also tightened its control over Kashmiri Muslim shrines through the newly applicable Waqf Act, 1995, banning age-old practices such as the collection of voluntary donations by hereditary priests.

Even the Indian Army has not shied away in trying to revise the region’s history to serve modern political motives. During his farewell address in May 2022, the outgoing General Officer Commanding of Srinagar-based 15 Corps deplored that, “Kashmir was a land of abundance and driver of its own destiny till the 13th century,” alluding to the point in history when Kashmir transitioned towards Islam. “In a sad turn of events, Kashmiris lost control over their destiny to foreign tyrants and invaders.”

A Move to Depoliticise the J&K Issue?

Political anthropologists said that these events are also being viewed in Kashmir as attempts to depoliticise Kashmir as a site of conflict — and simultaneously impose a new ‘value system’ upon the people who are already preoccupied with simmering anxieties over their cultural and political identity.

“There’s a sense that the new cultural changes being forced upon the society are part of the broader assault on Kashmiri identity per se,” said Mohamad Junaid, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.

With the laws that promised inherited protections of land ownership gone and the domicile rules amended, worries have abounded over how Hindutva agenda will pan out in Kashmir in the longer run. “Such anxieties cannot be labelled 'backward',” added Hussain.

“What is being hailed as ‘progressive thought’, is tied up irreversibly with this process of enforced integration, and for most Kashmiris, these changes are not just about ‘progress.’ They are a continuation of efforts to erode their distinct religious and cultural character.”

(Shakir Mir is an independent journalist whose work delves into the intersection of conflict, politics, history and memory in J&K. He tweets at @shakirmir. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined