'Direct' Rail Connectivity to Kashmir Isn't All That Direct

Kashmir-bound passengers will have to disembark at Katra and then pass through another round of security checks.

advertisement

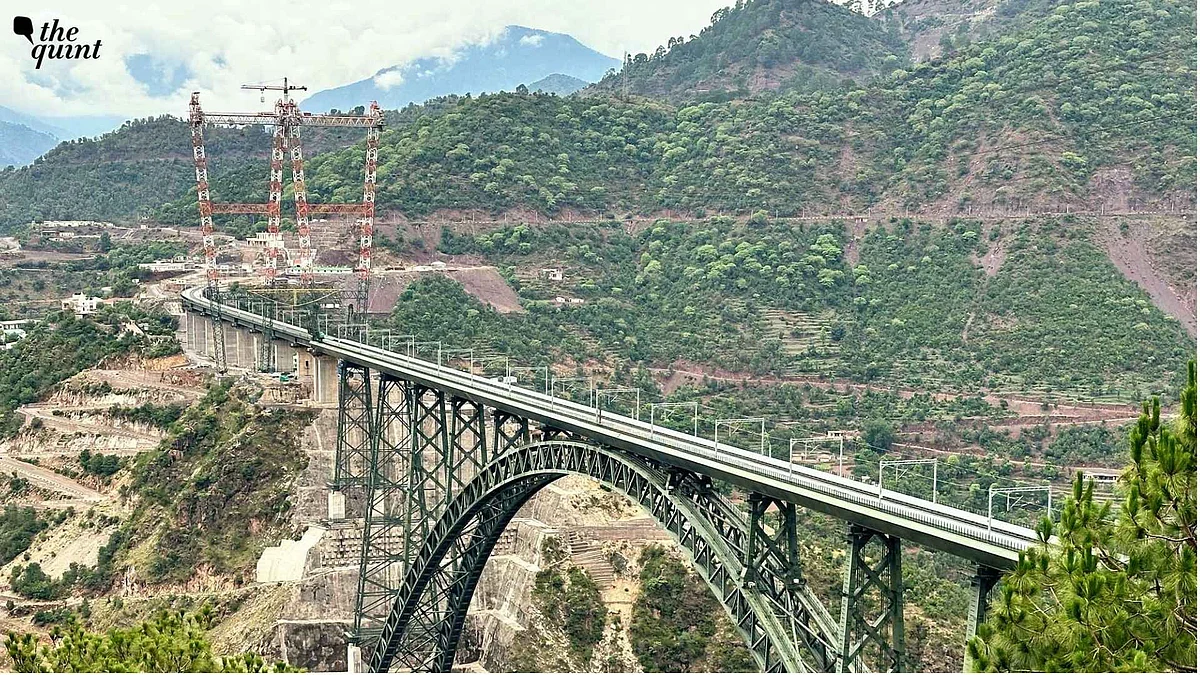

Fears and expectations are running high as the final upgradation on the 272-km-long Udhampur-Srinagar-Baramulla rail link is approaching completion. This will result in an uninterrupted railway line connecting the Kashmir Valley – where road access remains fraught with climate-related risks – to the rest of the country.

Built at an estimated cost of Rs 41,000 crore, the said project has been described by Union Railways Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw as "the most difficult railway project undertaken since Independence".

On 16 January, the commissioner of railway safety completed its final inspection of the 17 km section, after the completion of which the train will tear through the Pir Panjal mountain range of Jammu, and traversing a series of high-altitude bridges, chug into the scenic climes of the snow-bound town of Banihal, which abuts the Valley at its gateway.

From there, the line will merge with the Qazigund-Baramulla railway line (connecting the southern and northern parts of Kashmir) that is already operational – albeit developed in phases – since 2009.

A train runs on a railway track covered with snow as Baramulla-Banihal train service fully resumed after heavy snowfall in the Kashmir valley at Nowgam Railway station, in Srinagar in February 2022.

(Photo: IANS)

The Fresh Troubles

Last week, however, a new twist in the whole scheme of things dampened the anticipation. According to a new timetable issued by the Indian Railways, one Vande Bharat Express and two Mail Express trains will run daily between the railway stations of Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Katra in Jammu and Srinagar in Kashmir.

The timetable doesn’t say anything about the journey of the trains beyond Katra, leading to speculations that there won’t be a direct train service running uninterrupted between Kashmir and the rest of the country.

Although the reports were based on quotes from anonymous railway officials, the Ministry of Railways hasn’t rebutted them, indicating that they might not be unsubstantiated.

The Genesis of Kashmir’s Railway Dream

The direct train connection between Kashmir and the mainland has been a subject of intense debates in recent times. Although the project was initiated 30 years back, its completion and operationalisation is taking place amid the larger discourse about the erstwhile state’s ‘complete assimilation’ with the rest of the country.

Separately, the railways in 2014 extended the Udhampur line in Jammu (already operational since 2004) to Katra in the Reasi district which fans out into the craggy mountain ranges of Pir Panjal that gather around the Kashmir Valley on its southern side.

With this upgradation, the only portion which wasn’t yet connected through railways was the Katra-Banihal section. Owing to its difficult topography composed of rugged hills, ravines, mountain spurs, rivers and wide valleys, the construction of railway tracks was initially deemed impossible.

A file photo of an under-construction Anji Khad bridge, India's first cable-stayed railway bridge, during a media preview in Reasi district.

(Photo: PTI)

Last year in February, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the rail service extending the Banihal line further south towards Sangaldan, shortening the distance with Katra further. The next phase (which will conclude this month) will fill up this gap consisting of four more stations, completely linking Kashmir with the rest of the country via an all-weather train track.

The Perennial Fears and Anxieties

Within the Valley, the debates over railway connectivity have generated anxieties over the demographic changes that might take place as a consequence of enhanced mobility into the region where road accessibility remains cut off in the event of bad weather. In the southern plains in Jammu, the trading community apprehends that a direct train to Kashmir will lead to them being ignored.

Already beset by the controversy over his perceived deference to the BJP-led Union government, Chief Minister Omar Abdullah initially sought to justify the one-stop arrangement, saying that it was conceived keeping in mind the security of passengers. “If there are security concerns, then I don’t think there should be any objections,” he told the media. “After all, whosoever travels by train wishes for their safety and security, and so do we.”

Other regional leaders from political groups like the Apni Party and the People’s Democratic Party, however, slammed the decision, calling it 'humiliating' and an 'unnecessary burden', respectively.

Sensing that the news has triggered a sense of dismay in several quarters, Omar nuanced his position.

Will the Service Benefit the Union Territory?

Kashmir-based observers believe that adding a halting station to the rail journey between Jammu and the Valley defeats the whole purpose of train travel.

The economic experts, however, have weighed the situation differently, saying that even if the train journey isn’t going to be direct, it will still boost the local economy.

Imran Murtaza, who heads Snack-a-Boo, a food processing unit in Srinagar, told The Quint that 45 of his 50 employees are migrants from other regions.

(Shakir Mir is an independent journalist. He has also written for The Wire, Article 14, Caravan Magazine, Firstpost, The Times of India and more. He tweets at @shakirmir. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined