Fear and Loathing (of Ideas) in Srinagar: Why J&K Police are Raiding Bookshops

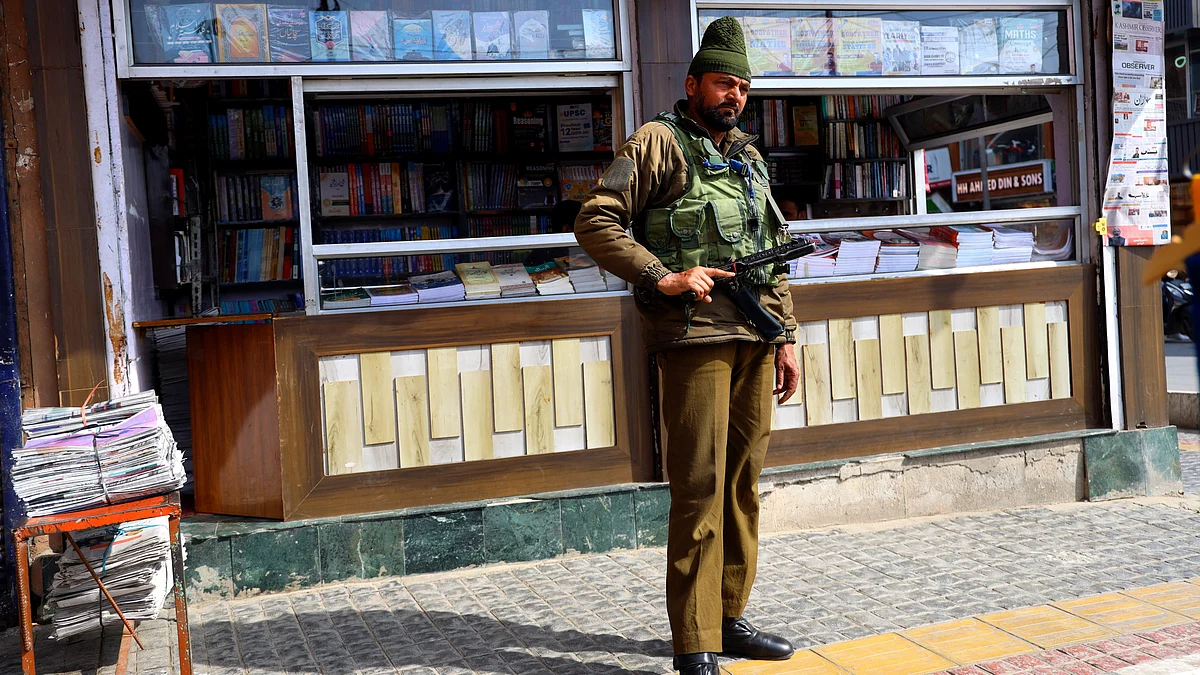

'They came, demanded the books, and left', a Kashmiri bookseller said amid crackdown on 'Islamist' literature.

advertisement

Last week, the Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) police initiated a series of raids across several parts of the valley. Over the last six years, such raids had become a common phenomenon, whether targeting individuals alleged to have supported militancy or those involved in trafficking illicit money or drugs.

This time, however, the raids were about books and hoardings. Police swooped down on scores of booksellers and private individuals in an unprecedented operation, demanding to know whether they possessed literature associated with the banned outfit Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI) in their possession.

A prominent bookseller in Srinagar’s Lal Chowk area told The Quint that police in civilian clothes visited his shop to inquire about books written by Abul A'la Maududi, the founding patriarch of the JeI in undivided India.

Jamaat-e-Islami’s Political Influence in Kashmir

Maududi laid the groundwork for an Islamist ideology that sought to synthesise the Islamic notions of governance with the fundamentals of representative democracy.

While the JeI has seen some success in Pakistan, it has largely floundered in India except in Jammu and Kashmir, where it formed an independent unit of its own. The regional chapter of the group had seen some degree of electoral ascendancy in the 1970s when it twice won the seats to the local legislature.

The group later lost ground as Kashmir crashed into insurgency and violence during the 1990s, with its cadres joining the ranks of the militant outfit Hizbul Mujahideen. Weakened by the sustained counter-insurgency operations, the group formally renounced violence in the early 2000s.

A 65-year-old bookseller in Srinagar’s Maisuma locality said that the police had come to inquire about the books, but could not not confirm if any titles were confiscated. He, however, gestured to another stall right across the road, indicating that it had been the actual target of a raid.

Kashmir range Inspector General of Police (IGP) Vidhi Kumar Birdi did not respond when asked for comments. However, in a tweet, the police justified their actions based on “credible intelligence regarding the clandestine sale and distribution of literature promoting the ideology of a banned organisation,” which led to the impounding of 668 books under Section 126 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), a provision dealing with maintaining public peace.

The Political Fallout and Rising Tensions

The raids have drawn sharp criticism from several quarters in the valley, raising political tensions in a region where the newly elected government, led by the National Conference (NC), already faces criticism — including from its own MP Aga Syed Ruhullah Mehdi — for not standing up to the central government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi

“I was just 20-year-old when I would carry the weighty volumes of Maududi’s ‘Tafheem-al-Quran’ on my back and bring them here,” the 65-year-old bookseller said, referring to Maududi’s famous exegesis of the Islamic religious text.

Separately, the brief detention of three women in Srinagar for allegedly distributing copies of the Quran ahead of Ramadan also sparked a political outcry in the union territory.

Mufti accused the present NC government of having a “tacit understanding” with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), allowing the Centre to wage “psychological warfare” in Kashmir.

A Entrenched Sense of Fear

At a bookshop near Gaw Kadal bridge, another bookseller expressed regret over the raids, though he denied his shop had

“It makes no sense,” he said. “All these books are published by Indian publishers and are available in cities like Delhi, Bengaluru and Lucknow. They are easily accessible on the Internet as well. How will seizing their titles help anyone anyway?”

As he spoke, a young man alighted from his two-wheeler and approached the bookseller, showing a book cover on his phone. “Do you have this book,” he asked, referring to Maududi’s ‘The Islamic Law and Constitution’ published in 1960. The owner shook his head. “No.”

When The Quint asked the man if he was aware that there was a crackdown underway on all written material authored by Maududi in Kashmir, he smiled sheepishly. “It isn’t for me. I need it for someone else.”

The sense of fear is hardly new. Over the last six years, J&K has seen rampant use of preventive detention laws such as the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and the Public Safety Act (PSA)

Many of these cases are likely linked to terrorism, but numerous journalists and scholars have also been targeted — and later released by courts.

Hopes Pinned on Omar

Last year’s Assembly elections were seen as an opportunity to push back against the crackdown. With an elected government now in place, locals hoped for greater checks on authoritarianism.

The elected government has, however, shrugged off the matters, claiming that it doesn’t currently enjoy any remit over police.

Opposition leaders like Waheed-ur-Rehman Para point out that CM Omar Abdullah was publicly associating with the central government’s actions pertaining to law and order in the region.

Tanvir Sadiq, a prominent legislator and senior NC spokesperson, said that the party understands there are high expectations.

“That is why we are seeking the restoration of statehood so that people are not harassed. They should feel free to exercise the rights that the Constitution gives them. As long as there isn’t any material or literature that goes against the national interests, I don't think anyone should have a problem with it.”

The Banned Organisation

Jamaat-e-Islami, J&K, was outlawed in February 2019, just days after the gruesome Pulwama attack, in which a suicide bomber associated with Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM) group blew up a Central Reserve Police Force (CPRF) motorcade on its way to Srinagar, killing 40 personnel.

The attack brought India and Pakistan to the brink of war. Although Jamaat’s connection to the attackers has not been proved, the BJP government — then nearing the end of its second term — sought to project a tougher image ahead of the parliamentary elections in May.

The action against Jamaat was intended to showcase a more ruthless and unforgiving response to militancy and separatism in J&K, especially as the government was in the process of stymying all potential “trouble-makers” ahead of the abrogation of Article 370’s in August later that year.

In June 2022, the J&K government also banned the schools run by Falah-e-Aam Trust (FAT), a Jamaat affiliate. The orders passed by the administration directed chief educational officers, zonal educational officers and principals to accommodate the students who would be left in need of new admissions as a consequence of such an action. An estimated 385 such schools were asked to wind up, impacting around one lakh pupils.

An eight-member panel, composed of individuals associated with JeI before it was banned, was constituted to work out the modalities for the proposed revocation. Some members of this panel went public, expressing their readiness to participate in the polls and even reaffirming their support for the integrity and sovereignty of the country.

That, however, did not materialise. Instead, the tribunal set up by the Union Home Ministry in June reconfirmed the ban for another five years.

‘A Futile Exercise’

Authors and researchers in the valley have called the ban counterproductive, arguing that it is likely to provoke more curiosity about the book than before.

Saleem Rashid Shah, a book critic and author of a forthcoming book on J&K leader Sheikh Abdullah, said that even from the perspective of someone evaluating the legacy of Maududi critically, the ban wouldn’t serve any meaningful purpose.

Political experts, however, said that despite the national leadership’s efforts to mainstream Jamaat, the ban was still imposed because of BJP’s ideological commitments.

“The current regime would think this ideology is somewhat disruptive and that it promotes a certain understanding of Islam which they do not consider well-meaning from their perspective of state-building,” said Noor Ahmad Baba, retired professor of political science who taught at the University of Kashmir. “They feel that it has contributed to a certain mindset and promoted a certain understanding of the conflict. That way it makes sense for them to clamp down on the sale of books.”

(Shakir Mir is an independent journalist whose work delves into the intersection of conflict, politics, history and memory in J&K. He tweets at @shakirmir. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined