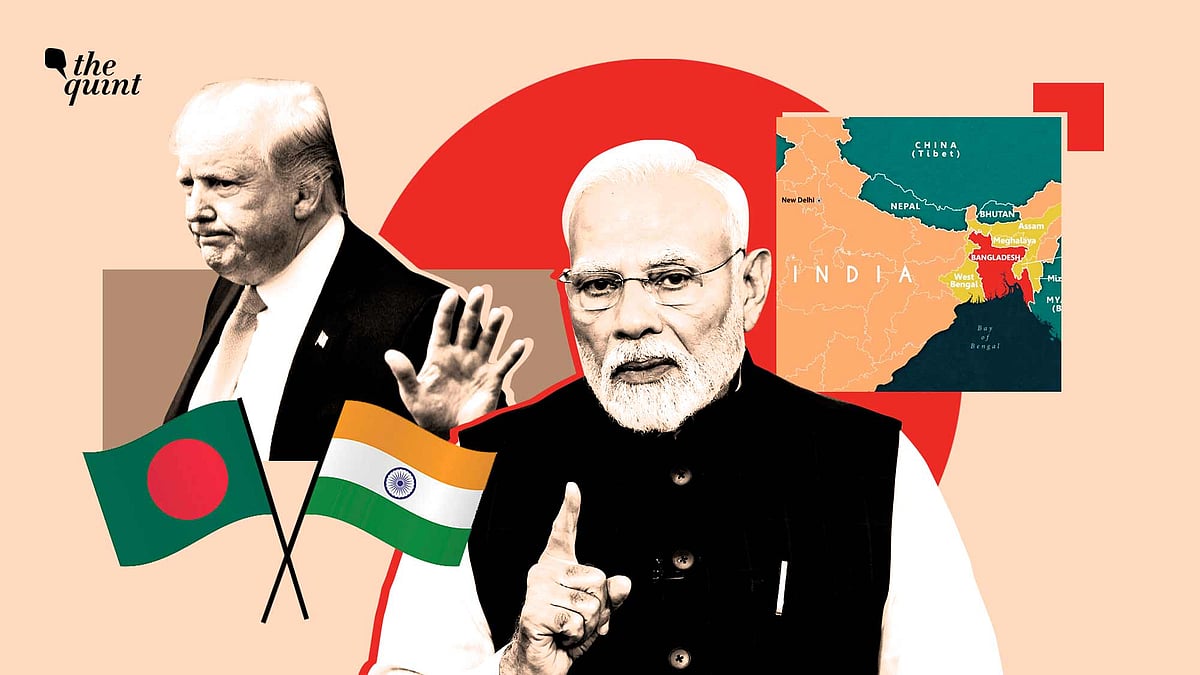

India's Trade Tariff Tactics Against Bangladesh Could Backfire—Just Ask Trump

A trade war is better than a bloody shooting war, or is it, asks Sanjay Kapoor.

advertisement

Imposition of tariffs by one country on another can be mean and hurtful.

Ever since taking over the Oval Office for the second time, US President Donald Trump has tried to weaponise trade and tariffs as a way to make America great again, albeit at the expense of every other nation (and even his own American markets). Trump has arbitrarily used the threat of tariffs even against countries that believed that they were allies of the US.

Trump has, however, shied away from hurting geopolitical giants like Russia, and has hastily put off the tariff imposition on China by many months after making a series of public threats.

Till a court restored his emergency powers and shot down an earlier judgment of a federal court that took away his powers to impose tariffs on nations. Only token ones on auto manufacturers remained.

Weaponising Trade

Trump and his administration have claimed that the sudden ceasefire after a four-day "war" between India and Pakistan that saved millions of lives, was their doing. The American claim is that the ceasefire was an outcome of clever use of tariffs and that India and Pakistan—both nuclear powers— were given trading access to the US if they ended the war. An affidavit to the same effect signed by top US officials, including Trump, was also submitted in a federal court amid a hearing on Trump's invocation of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to implement global tariffs exeeding his legal mandate.

The Indian government has denied US mediation.

Though this judgment could be challenged in the US Supreme Court, Trump’s actions have been inspiring other countries, including India, to make opponents see reason. The big question is whether tariffs can be weaponised or they can merely antagonise impacted countries.

Of late, India has weaponised trade against Pakistan and Bangladesh with mixed results. At least with Bangladesh, the two countries have drifted in two directions.

At that time, the Indian government had imposed 200 percent tariff on goods to Pakistan. Now everything has been shut down.

Ajay Srivastava, co-founder of Global Trade Research Initiative, a body that tracks trade, told Business Standard that the move is "largely symbolic" since India had already imposed 200 percent tariffs on Pakistan after the 2019 Pulwama attack. It had also scrapped Pakistan's status as the 'most favoured nation', which effectively reduced imports from Pakistan to just $0.42 million between April 2024 and January 2025.

“Pakistan still needs Indian products and may continue accessing them through third countries using recoded or unrecorded routes," Srivastava was quoted by the outlet as saying.

According to an Al Jazeera report, however, informal trade between the two hostile neighbours is higher than official data shows, and that a quiet, unofficial annual trade of $10 billion (in exports from India) between India and Pakistan exists, carried out largely through third-party countries.

Not the First Time with Pakistan

This is not the first time that this kind of strictness has been imposed on trade with Pakistan. Restrictions on trading were imposed during and after the Indo-Pak wars that have taken place in 1948, 1965 and 1971.

There has been discussion on whether trade and terror can co-exist between India and Pakistan.

This is where the example of China and the high trade volume—usually bandied to show that trade between the two countries has not been really hurt by a gnawing, unending border dispute—becomes interesting. Indian voices have also accused the Chinese of supporting terrorists from Pakistan. The Chinese claim to be its 'iron brother'. But India-China trade never stopped.

Actions against the Chinese government have been more at the level of the ruling party’s IT cell or the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) cadres calling for boycott of Chinese commodities. This is very similar to Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently asking for replacing foreign made goods with indigenously made products.

Quite visibly, the Indian government has been cautious in handling China and its trade policies. Indeed, if India had shown impatience towards China due to the unresolved border dispute or even after the Galwan clash of June 2020, it has evaporated now.

Bangladesh Gets Shorter End of the Trade Stick

In contrast, India did not adopt a similar yardstick with Bangladesh—which has moved away from its arc of influence after Sheikh Hasina was ousted on 5 August 2024—as it does with China.

After Muhammad Yunus took over as the advisor and began to make hostile noises towards New Delhi, the Indian government began to unhinge itself from Dhaka. The Indian government was angry over Yunus' remarks inviting China to trade with landlocked northeast through Dhaka.

India conducted itself like a regional power and imposed restrictions on Bangladeshi goods' access to the Northeastern market. India also ended the transshipment facility to Bangladesh that allowed various items to be exported to countries of the Middle East and Europe. This excluded Nepal and Bhutan.

The move was a body blow to Dhaka, which in New Delhi’s view, has been supping with Pakistan, India's perennially hostile neighbour. The insinuation is that Yunus and Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif have mended broken ties after the 1971 war.

The Delhi-based business news daily recently claimed that New Delhi's sanctions may "restrict Bangladeshi exports worth $770 million to India—nearly 42 percent of the neighbouring country’s global export earnings—by barring several goods from land routes and limiting them to a few sea ports.”

As the regional tensions and geopolitical conflicts rage on, the Indian government may be picking up ideas about how to tame its rivals and those who mess with it in the near and far future from the West. But it would have to figure what to do next when “beautiful bills” of the US come to grief. If they work, then Trump can safely say that a trade war is better than a bloody shooting war.

(Sanjay Kapoor is a veteran journalist and founder of Hardnews Magazine. He is a foreign policy specialist focused on India and its neighbours, and West Asia. This is an opinion piece. All views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined