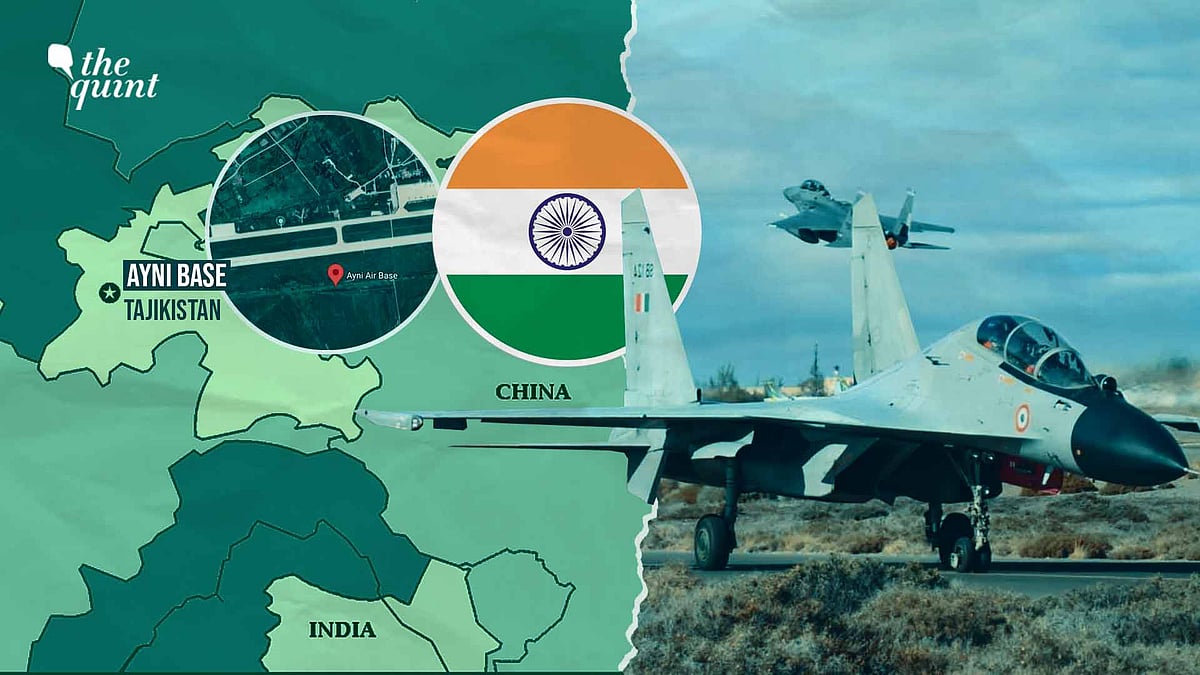

India's Exit from Tajikistan's Ayni Shows Multipolarity Also Has Its Limits

Was it Chinese pressure or India's growing 'outlier' image in the region? India must introspect on its Ayni exit.

advertisement

It is now official. India has officially—if rather quietly—vacated the Ayni airbase it had administered in the Republic of Tajikistan in 2022. The withdrawal took place in 2022 and was completed in 2023. This puts to rest all speculation and ambiguity surrounding the status of ths airbase.

The Ayni airbase was India’s only full-fledged overseas military base, in a strategically significant location. Tajikistan sits at the junction of China, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. It has the longest land border with Afghanistan.

Laying just 10 km west of the capital Dushanbe, approximately 20 km from Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor, which connects it to China's Xinjiang province and borders Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK), the significance of such a location was not lost on India.

Ayni not only gave India a presence in Central Asia—a region that we have identified as strategically important to us—but it also offered us access to Afghanistan, PoK, as well as proximity to Chinese Xinjiang.

Soviet Moorings, Desi Ties

A major Soviet military base, Ayni's infrastructure deteriorated significantly after the dissolution of the USSR. Tajikistan, economically the least developed of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and reeling under the impact of a long and bitter civil war, was hardly in a position to renovate it. India did.

Operating the base from 2002-2022, India spent around $80 million to renovate it, upgrading the runway to 3,200 meters to make it suitable for combat jets and heavy lift transport aircraft, and building new hangars. At one point, up to 200 Indian military personnel—mostly from the Indian Army and the Air Force—were also stationed at the airbase along with a few Sukhoi 30 MKI jets.

Notably, the base was used to evacuate Indian nationals in 2021 from Kabul, in the wake of the Taliban takeover. The Opposition parties have termed the withdrawal as a “strategic failure of diplomacy” of the government. What adds to the sombreness is the timing—in the wake of Operation Sindoor and at a time when India finds itself in a pivotal moment vis-s-vis the Taliban.

It has been reported that Tajikistan did not extend the airbase lease to India after 2022 under joint Russia-China pressure, though Tajik officials, on the condition of anonymity, have refuted these allegations. Analysts note that, unlike other powers that maintain foreign bases through long-term leases or mutual defence pacts, India depended on diplomacy and the goodwill of the Tajiks.

If the above is indeed true, then it could be possible that India had misread the ongoing dynamics in such a sensitive region. What would make this further poignant is that Central Asia in general, and Tajikistan in particular, has been a place where India had had a natural edge in terms of cultural affinity with a groundswell of goodwill for it—a natural legacy of the region's Soviet past. Bollywood had played a particularly pivotal role, as it continues to play even now. For instance, 'Indira' is a common female name in these parts, after former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. A diplomat in a Central Asian country from where I returned a couple of days ago, told me that she had had a Bollywood-themed wedding, though she has never set foot in India. There are numerous such stories of cultural inflections in the region.

The Chinese Conundrum

In fact, it was China which had had territorial disputes with many of the countries in the region, including with Tajikistan, which remained wary of it for long. When India joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), of which Russia, China, and Tajikistan, along with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, are founding members, it is believed that its entry was facilitated by Russia to balance China's widening footprint in Central Asia, Russia 's traditional sphere of influence.

It has become Tajikistan’s largest trading partner, surpassing Russia in bilateral trade volume, according to data from the Tajikistan Statistics Agency.

Between January and May 2025, trade between Tajikistan and China reached $964 million. It was the first in the region to sign up to China's Belt and Road Initiative, and is an import node in it.

China has conducted large-scale infrastructure projects there and has emerged Tajikistan’s largest external creditor.

As of early 2025, Dushanbe’s debt to Beijing stood at around $1 billion, representing nearly one-third of the country’s total external debt.

While Tajikistan is a member of the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation and houses a large Russian military base, China has also been deepening its security cooperation with Tajikistan. Russian preoccupation with the Ukraine conflict may have been a factor that enabled China to establish a military facility in Tajikistan’s sensitive Pamir region in 2016. It is supposed to be China’s first security facility in the region and the first outside its territory.

More recently, in 2021, the Chinese built a paramilitary facility in the sensitive Wakhan Corridor. A Carnegie International study found that it was Tajikistan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs that invited the Chinese government to fund such a facility, and not, as is usually thought, a Chinese demand.

Why is India Falling Out of Favour?

After all, India, despite not having China's deep pockets, has also spent millions of dollars in both aid and grants, building infrastructure, IT centres, pharmaceutical factories, in Tajikistan, besides funding numerous scholarships for Tajik students. Yet, in the region we are often perceived as being lacklustre and half-hearted in our engagement with it.

In 2012, India announced its "Connect Central Asia " policy—a good 20 years after the emergence of the Central Asian states as independent and sovereign states. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 2015 visit to all the five states in the region created a momentum in India-Central Asia ties, which assumed further urgency because of the crisis swirling around Afghanistan. Partnering with the region was and remains crucial for the stabilsation and economic integration of Afghanistan with the region. Hence, in 2019 the India-Central Asia Dialogue at the level of Foreign Ministers was initiated.

Yet the fourth such dialogue, held this year in Delhi in June, came after a gap of four years.

Similarly, in 2022, India initiated the India-Central Asia Leaders' Summit. Because of Covid-19 disruptions and logistics, it was convened virtually. As if taking a cue from India already after it had announced its intention to convene such a summit, China hastily announced one and convened a similar virtual summit with Central Asian leaders on the eve of India-Central Asia summit. India is yet to convene the second such summit.

China, meanwhile, has already convened two more summits—in person—with Central Asian leaders. While the first in-person summit was held in 2023 in Xian, the second was held earlier this year in Astana, the Kazakh capital, bringing the total number of leader summits to three.

When India assumed the SCO chair in 2023, it expended considerable capital and effort into convening hundreds of meetings. However, the last-minute decision to convene the summit meeting virtually did not go down too well with many of them, though they understood India's compulsions, given it was also hosting the G20 summit that very year. Similarly, the Prime Minister's decision to skip the 2024 SCO summit in Astana was read by some of them as India's non-interest in the organisation. After all, one of India's prime aim in joining the SCO was to use it as a platform for regular meetings and engagement with its Central Asian partners. Central Asian leaders, who were once regular visitors here, keen to forge closer ties with India and emulate its success stories, are now seen more often in other capitals.

A Regional Outlier

India is, thus, seen to be as something of an outlier state in the larger Eurasian region. Moreover, around the same time that India's lease of Ayni airbase expired, India began exporting weapons to a Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) member-state—Armenia—that was disgruntled with Russia.

The loss of Ayni is a strategic setback for India and painful, especially when India has been seeking to project power outside South Asia, investing in military facilities in places like Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan and trying to establish a foothold in Central Asia. But it can serve as a wakeup call to India. Soft power and goodwill, important as they are, alone are not enough, India needs to rethink its approach to the region.

(The author is an award-winning journalist specialising on Eurasian affairs. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined