The Rich Indian’s Guide to Getting Away With a Hit-and-Run

The playbook largely stays the same. The wealthy will always have the money and connections to get away.

advertisement

Every rich Indian with a fleet of fancy cars and an entitled heir knows the unwritten manual for hit-and-run cases by heart. We all know its title: The Driver Did It. Aravind Adiga immortalised this open secret in 2008’s award winning White Tiger, his eviscerating take on Delhi society that drew straight from headlines.

Who’s to say if many of these tycoon dads skip the “drive responsibly” talk with their progeny, jumping straight to “If Indian roads don’t part for you as you go from 0 to 100 km in 2.5 seconds, find a driver ASAP.”

As he speaks, daddy may stretch out his arm with a Biblical flourish, mimicking the splitting of the Red Sea, informing his successor that until their eighteenth birthday, the top court will likely try them as a juvenile if they should ever have the misfortune of getting caught.

The Familiar Script After Every Crash

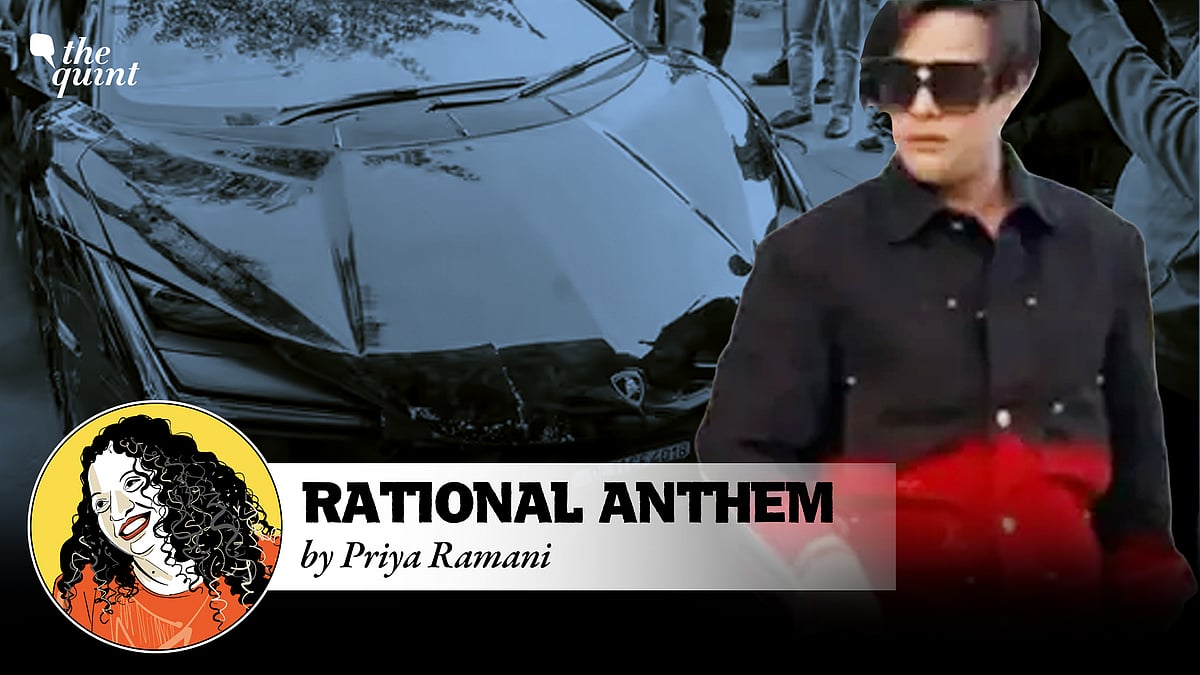

When Shivam Mishra, 35, son of tobacco baron KK Mishra, crashed his speeding Lamborghini Revuelto into pedestrians and vehicles on Kanpur’s VIP road (many high-ranking government officials live here), injuring six people, it was quickly termed the Kanpur Lamborghini case.

It took its place in the pantheon of similar cases: The Delhi Mercedes disaster in 2016 where an underage driver with an over-speeding record flung a pedestrian crossing the road 15-20 feet killing him; the Pune Porsche tragedy of 2024 where a builder’s son, 17 and intoxicated, mowed down two men; and the Mumbai BMW horror of 2024 where a politician’s son slammed into a couple on a two wheeler, not stopping and dragging the woman on the bonnet of the car before she got entangled in its wheels for over 1.5 km.

So what if CCTV footage showed that Shivam Mishra was driving the car and eyewitnesses saw him being pulled out of the driver’s side? Mishra’s lawyer argued that his client was “wrongfully arrested”.

Mohan, a driver employed by the family, submitted an affidavit in court saying he was at the wheel when the accident occurred. His fatalistic, bald narration of events is chilling. You can watch it here.

How Stories Change Overnight

Shivam’s father, tobacco baron KK Mishra assured reporters that “Everything that anyone including the police was saying was wrong”. He insisted his son was just a passenger in the car and spun an ingenious story of a medical emergency, a panicky driver, and a head on collision.

The injured man who had filed the complaint, suddenly said that a driver had been driving the car. Within days, the story morphed before our eyes.

Many argue that the driver accepts responsibility for the crime because he was paid a hefty amount by his employer, one that might take him years to earn in his day job. He’s probably thinking of his family, they say.

The Disposable Men Behind the Wheel

In Adiga’s fiction, the driver, the protagonist of the story, offers an alternative: “The jails of Delhi are full of drivers who are there behind bars because they are taking the blame for their good, solid middle-class masters,” Balram says. “We have left the villages, but the masters still own us body, soul, and arse.”

According to its website, Lamborghini’s super sports car has a maximum speed capacity greater than 350 km/h. As someone who lives in a city where peak traffic speeds are 10-20 km/h on major roads; speed bumps crop up faster than you can change gears; and craters and potholes inspire art and activism (and are often the cause of driver and pedestrian deaths), it’s incomprehensible how anyone could utilise the speed potential of a luxury car in any of our metros or towns.

It’s fine to buy a Lamborghini to show it off, but where exactly can you drive it safely? Incidentally, Mumbai’s state transport department has started issuing lakhs of challans for traffic violations on the Atal Setu, India’s longest sea bridge. Speeding above 100 kmph is the number one violation.

India’s Hit-and-Run Crisis Is Bigger Than the Rich

If we are being honest, luxury cars are only the poster boys of India’s hit-and-run epidemic. The contrast of a 10 crore car driven by a possibly inebriated man—we will never know if Shivam Mishra was intoxicated because he was absconding for 90 hours after the accident—who has access to a vast fortune, and who slams into humble pedestrians, represents the nadir of this common crime.

Hit-and-runs were responsible for 18 percent or 30,486 road accident deaths in 2022, the last year the government released this data. But some states release granular data that shows an alarming trend. Ahmedabad traffic police data, for example, showed that hit-and-runs had shot up by 49 percent in 2025, compared to the previous year.

The government recently increased prison time for hit-and-run cases to 10 years from the previous two years, but the data on who exactly goes to jail is never provided. If you report the accident instead of fleeing, the jail term falls to five years.

If you’re Salman Khan, your case will never be described as the Mumbai Land Cruiser case of 2002. If you drive an Aston Martin, the media may black out the reporting of the hit-and run, like they did in 2013. But the playbook largely stays the same. The wealthy will always have the money and connections to get away. And the poor will be made to atone for their crimes.

(The author is the founder of India Love Project and on the editorial board of Article 14. This is an opinion piece. All views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)

- Access to all paywalled content on site

- Ad-free experience across The Quint

- Early previews of our Special Projects

Published: undefined